The most complicated, powerful computers in the world—performing the most intense processing tasks ever devised by man—all rely on Linux. This is an amazing feat for the little Free Software Kernel That Could, and one heck of a great bragging point for Linux enthusiasts and developers across the globe.

But it wasn't always this way.

In fact, Linux wasn't even a blip on the supercomputing radar until the late 1990s. And, it took another decade for Linux to gain the dominant position in the fabled "Top 500" list of most powerful computers on the planet.

To understand how we got to this mind-blowingly amazing place in computing history, we need to go back to the beginning of "big, powerful computers"—or at least, much closer to it: the early 1950s.

Tony Bennett and Perry Como ruled the airwaves, The Day The Earth Stood Still was in theaters, I Love Lucy made its television debut, and holy moly, does that feel like a long time ago.

In this time, which we've established was a long, long time ago, a gentleman named Seymour Cray—whom I assume commuted to work on his penny-farthing and rather enjoyed a rousing game of hoop and stick—designed a machine for the Armed Forces Security Agency, which, only a few years before (in 1949), was created to handle cryptographic and electronic intelligence activities for the United States military. This new agency needed a more powerful machine, and Cray was just the man (hoop and stick or not) to build it.

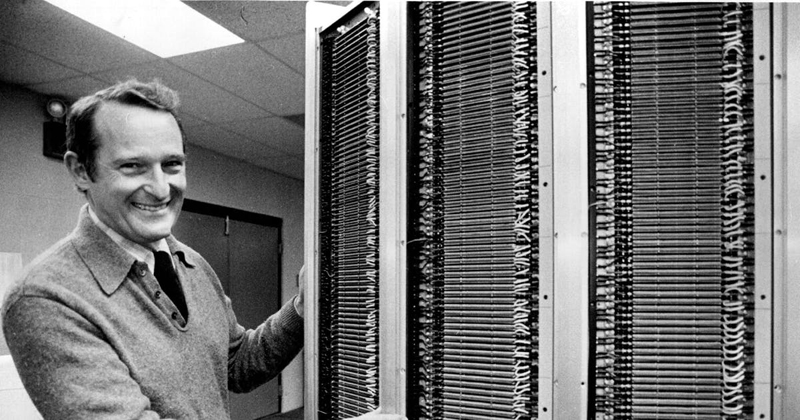

Figure 1. Seymour Cray, Father of the Supercomputer (from http://www.startribune.com/minnesota-history-seymour-cray-s-mind-worked-at-super-computer-speed/289683511

This resulted in a machine known as the Atlas II.

Weighing a svelte 19 tons, the Atlas II was a groundbreaking powerhouse—one of the first computers to use Random Access Memory (aka "RAM") in the form of 36 Williams Tubes (Cathode Ray Tubes, like the ones in old CRT TVs and monitors, capable of storing 1024 bits of data each).

In 1952, Cray requested authorization to release and sell the computer commercially. The Armed Forces Security Agency agreed to the request (so long as a few super special instructions were removed that they felt should not be in the hands of the public). The result was the Univac 1103, released at the beginning of 1953, ushering in the era of supercomputers.

And, with that, the supercomputer industry was born.

Note: the Armed Forces Security Agency? It still exists—sort of. Nowadays you might recognize it by a more familiar name: the National Security Agency. That's right, we can credit the NSA for helping kickstart supercomputing.

Throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the supercomputer continued to flourish. Faster machines were made. More machines were sold. Governments, companies and researchers of the world became increasingly reliant on these mammoth beasts to crunch ever-growing sets of data.

But there was a big problem: the software was really hard to make.

The earliest supercomputers, such as the Univac 1103, used simple time-sharing operating systems—often ones developed in-house or as prototypes that ended up getting shipped, such as with the adorably named Chippewa Operating System.

Note: the Chippewa Operating System was developed in the town of Chippewa Falls, located on the Chippewa River, in Chippewa County. That 11,000-person town in Wisconsin was the birthplace of Seymour Cray...and, arguably, the birthplace of supercomputing.

Figure 2. Univac 1103 at NASA's Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory (Image from https://images.nasa.gov/details-GRC-1955-C-39782.html

As time went on, the engineering investment required to develop, test and ship the operating system properly (and corresponding software stack) for these supercomputers was (in many cases) taking longer, and costing more, than the creation of the hardware itself. Obviously things needed improve.

For many years, the solution came in the form of licensing and porting existing UNIX systems. This brought with it large catalogs of well tested (usually) and well understood (sometimes) software that could jump-start the development of task-specific software for these powerhouses.

This was so popular and successful, that UNIX variants—such as UNICOS, a Cray port of AT&T's UNIX System V—dominated the supercomputing market to an extreme degree. Out of the 500 fastest machines, only a small handful (less than 5%) were running something other than UNIX.

Note: UNIX System V (originally by AT&T) was a key component of the (in)famous SCO lawsuits relating to Linux. Richard Stallman is also once quoted as saying System V "was the inferior version of Unix".

As great as this was...it wasn't ideal. Licensing fees were high. The pace of advancement was slow(-er than it should have been). The supercomputer industry was geared up and ready for change.

In June 1998, that change arrived in the form of Linux.

Known as the "Avalon Cluster", the world's first Linux-powered supercomputer was developed at the Los Alamos National Laboratory for the (comparatively) tiny cost of $152,000.

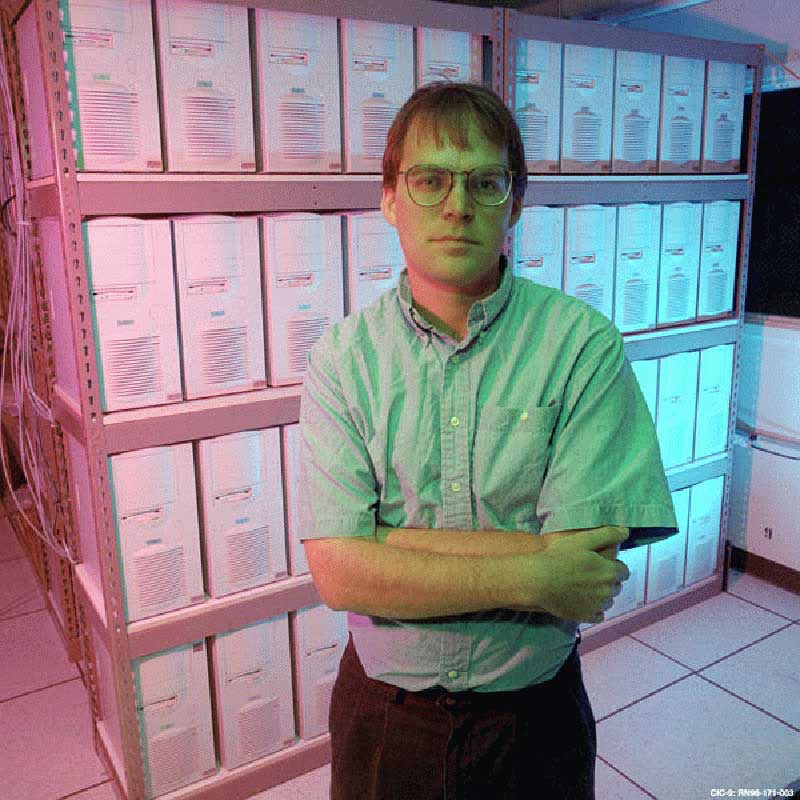

Figure 3. Michael Warren, Theoretical Astrophysicist, in Front of a Bank of Avalon Nodes (from https://docs.huihoo.com/hpc-cluster/avalon/)

Composed of a cluster of DEC Alpha computers (68 cores in total) and powered by 531MHz EV56 CPUs, this Linux-y beast pumped out a whopping 19.3 Gigaflops—just enough to help it debut as the 314th most powerful computer on Earth.

Sure, coming in 314th place may not seem like a win, but everyone has to start somewhere! And in 1998, this was downright amazing. In fact, this was, at the time, one of the cheapest dollar-per-Gigaflop supercomputers you could build.

That price-to-performance ratio grabbed a lot of attention among research labs and companies on tight budgets. With that single system, Linux made a name for itself as the "poor man's supercomputer system", which is much more of a good thing than it sounds like, resulting in multiple organizations investing in Linux-based computing clusters almost immediately.

Within two years—by around the year 2000—there were roughly 50 supercomputers on the top 500 list powered by our favorite free software kernel. From zero to 10% of the market in two years? I'd call that one heck of a big win.

Thanks, in large part, to that little cluster of DEC Alphas in Los Alamos.

If you ever want a lesson in how quickly an entire industry can change, look no further than the supercomputing space between 2002 and 2005.

In the span of three short years, Linux unseated UNIX and became the king of the biggest computers throughout the land. Linux went from roughly 10% market share to just shy of 80%. In just three years.

Think about that for a moment. Right now it's 2018. Imagine if in 2021 (just three years from now), Linux jumped to 80% market share on desktop PCs (and Windows dropped down to just 10% or 20%). Besides being fun to imagine (sure brought a smile to my face), it's a good reminder of just how astoundingly volatile the computing world can be. In this case, luckily, it was for the better.

As amazing as 80% market share was, Linux clearly wasn't satisfied. A point had to be made. A demonstration of the raw power and unlimited potential of Linux must be shown to the world.

Preferably on television. With Alex Trebek.

In 2011, Linux won Jeopardy.

Well, a Linux-powered supercomputer, at any rate.

Watson, developed by IBM, consisted of 2,880 POWER7 CPU cores (at 3.5GHz) with 16 terabytes of RAM, powered by a Linux-based system (SUSE Linux).

And, it easily beat the two top Jeopardy champions of all time in what has to be one of the proudest moments for Linux advocates the world over. News articles and TV shows across the land promoted this event as a "Man vs. Machine" showdown, with the machine winning.

Watson had enough horsepower to process roughly one million books every second—with advanced machine learning and low latency—allowing it to prove that it was far superior to humans at trivia games. On TV.

Yet, despite that overwhelming show of intellectual force, Watson never actually made the list of the Top 500 supercomputers. In fact, it never even was close—falling significantly short of even the slowest machines on that illustrious list. If that isn't a clear sign of our impending enslavement by our computer overlords, I don't know what is.

I suppose we can take some solace in the fact that it's running Linux. So, there's that.

Are you running Red Hat Enterprise on your servers or workstations? How about Fedora or CentOS?

Well if so, you're in good company—really, crazy, over-the-top good company.

As of November 2018 (the most recent Top 500 Supercomputer List), the fastest computer in the world, IBM's "Summit", runs Red Hat Enterprise 7.4.

Figure 4. IBM's Summit Supercomputer (Image from ORNL Launches Summit Supercomputer, CC 2.0)

When I say "fastest computer", that is, perhaps, a bit of an understatement. This machine clocks in at more than 143 petaflops—50 petaflops faster than any computer ever built. In fact, it is more than 7.4 million times faster than that first Linux supercomputer: the Avalon Cluster.

To give that a visual: if the Avalon Cluster is represented by walking, slowly, at one mile per hour...Summit would be walking to the moon. In two minutes. [Insert obligatory "but can it run crysis" joke here.]

Summit is composed of 4,356 individual nodes—connected to each other using Mellanox dual-rail EDR InfiniBand—each powered by dual Power9 22-core processors and 6 NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs.

Total power draw: 8,805 kW. Yeah, you probably don't want to run the microwave with this bad-boy turned on. Might pop a fuse.

As crazy as that power consumption number is, the IBM Summit (which currently sits at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory) uses roughly half (no joke) the power of both of the next two supercomputers: IBM's own Sierra (in spot number 2) and China's number-three-ranked Sunway TaihuLight—both of which are nearly tied in performance.

Sunway TaihuLight is also Linux-powered (using Sunway's in-house developed RaiseOS) and clocks in at a whopping 93 petaflops. Until the Summit came along, TaihuLight was the king, dominating the supercomputer performance list for the past two years.

And, those are just the top three. Numbers 4 through 500 all run Linux too.

That's right. Every single supercomputer—at least every one that broke the speed barrier and made it into the top 500 list—is running Linux. Every one. 100% market share of the current fastest computers the world has ever seen.

Call me crazy, but I'd declare that a teensy, tiny victory.

One might argue that, having reached 100% market share, there's nowhere to go...but down. That, with the volatility of the computing industry (supercomputing in particular), Linux eventually could become unseated from our high, golden throne.

I say, nay. This is a challenge. Think of it like playing King of the Hill. UNIX held the top-dog spot for a few decades. I bet we can beat that record.