With the recent news of Microsoft's acquisition of GitHub, many people have chosen to research other code-hosting options. Self-hosted solutions like GitLabs offer a polished UI, similar in functionality to GitHub but one that requires reasonably well-powered hardware and provides many features that casual Git users won't necessarily find useful.

For those who want a simpler solution, it's possible to host Git repositories locally on a Linux server using a few basic pieces of software that require minimal system resources and provide basic Git functionality including web accessibility and HTTP/SSH cloning.

In this article, I show how to migrate repositories from GitHub, configure the necessary software and perform some basic operations.

The first step in migrating away from GitHub is to relocate your repositories to the server where they'll be hosted. Since Git is a distributed version control system, a cloned copy of a repository contains all information necessary for running the entire repository. As such, the repositories can be cloned from GitHub to your server, and all the repository data, including commit logs, will be retained. If you have a large number of repositories this could be a time-consuming process. To ease this process, here's a bash function to return the URLs for all repositories hosted by a specific GitHub user:

genrepos() {

if [ -z "$1" ]; then

echo "usage: genrepos <github username>"

else

repourl="https://github.com/$1?tab=repositories"

while [ -n "$repourl" ]; do

curl -s "$repourl" | awk '/href.*codeRepository/

↪{print gensub(/^.*href="\/(.*)\/(.*)".*$/,

↪"https://github.com/\\1/\\2.git","g",$0); }'

export repourl=$(curl -s "$repourl" | grep'>Previous<.

↪*href.*>Next<' | grep -v 'disabled">Next' | sed

↪'s/^.*href="//g;s/".*$//g;s/^/https:\/\/github.com/g')

done

fi

}

This function accepts a single argument of the GitHub user name. If the

output of this command is piped into a while loop to read each

line, each line

can be fed into a git clone statement. The repositories will be

cloned into the /opt/repos directory:

genrepos <GITHUB-USERNAME> | while read repourl; do

git clone $repourl /opt/repos/$(basename $repourl |

↪sed 's/\.git$//g')

pushd .

cd /opt/repos/$(basename $repourl | sed 's/\.git$//g')

git config --bool core.bare true

popd

done

Let's run through what this while loop is doing. The first line

of the while

loop simply clones the GitHub repository down to /opt/repos/REPONAME, where

REPONAME is the name of the repository. The next four lines set the

core.base attribute in the repository configuration, which allows remote

commits to be pushed to the server (pushd and popd are used to preserve the

working directory while running the script). At this point, all repositories

will be cloned.

One way to test the integrity of the repository is to clone

it from the local filesystem to a new location on the local filesystem. Here

the repository named scripts will be cloned to the scripts

directory in the user's home directory:

git clone /opt/repos/scripts ~/scripts

The contents of the ~/scripts directory will contain the same files as the

/opt/repos/scripts directory. Verifying the commit logs between the two

repositories should return identical log data (run git log from the

repository directory). At this point, the GitHub repositories are all in

place and ready to use.

Having repositories on a dedicated server is all well and good, but if they can't be accessed remotely, the distributed nature of Git repositories is rendered useless. To achieve a basic level of functionality, you'll need to install a few applications on the server: git, openssh-server, apache2 and cgit (package names may vary by distribution).

Having reached this point in the process, the git software already should be installed. The SSH server will provide the ability to push/pull repository data using the SSH protocol. Out-of-the-box configuration for SSH will work properly, so no customization is necessary. Apache and cgit, on the other hand, will require some customization.

First, let's configure the cgit application. The cgit package contains a configuration file named cgit.conf and will be placed in the Apache configuration directory (location of configuration directory will vary by distribution). For increased flexibility with the Apache installation, make these modifications to the cgit.conf file:

<Macro CgitPage

$url>.</Macro>./cgit with $url (note that /cgit/ will be replaced with $url/).

The resulting configuration file will look something like the following (note that some of the paths in this macro might differ depending on the Linux distribution):

<Macro CgitPage $url>

ScriptAlias $url/ "/usr/lib/cgit/cgit.cgi/"

RedirectMatch ^$url$ $url/

Alias /cgit-css "/usr/share/cgit/"

<Directory "/usr/lib/cgit/">

AllowOverride None

Options ExecCGI FollowSymlinks

Require all granted

</Directory>

</Macro>

This macro will streamline implementation by allowing cgit to be enabled on

any VirtualHost in the Apache config. To enable cgit, place the below

directive at the bottom of the default <VirtualHost> definition. If you

can't find the default VirtualHost, a new

VirtualHost may be created, and this

directive may be added to the new VirtualHost.

In this example, you're using /git as the URL where cgit will be accessed. Upon installation, cgit was not installed with a default configuration file. Such a configuration file is generated when the application is accessed for the first time. The new configuration file will be located in the /etc directory and will be named cgitrc. You can access the cgit application at the following URL: http://HOSTNAME/git.

Once the URL has been accessed, the configuration file will be present on the filesystem. You now can configure cgit to look in a specific directory where repositories will be stored. Assuming the local repository path is /opt/repos, the following line will be added to the /etc/cgitrc file:

scan-path=/opt/repos

The scan-path variable sets the directory where the Git repositories are

located. (Note that cgit has other customization options that

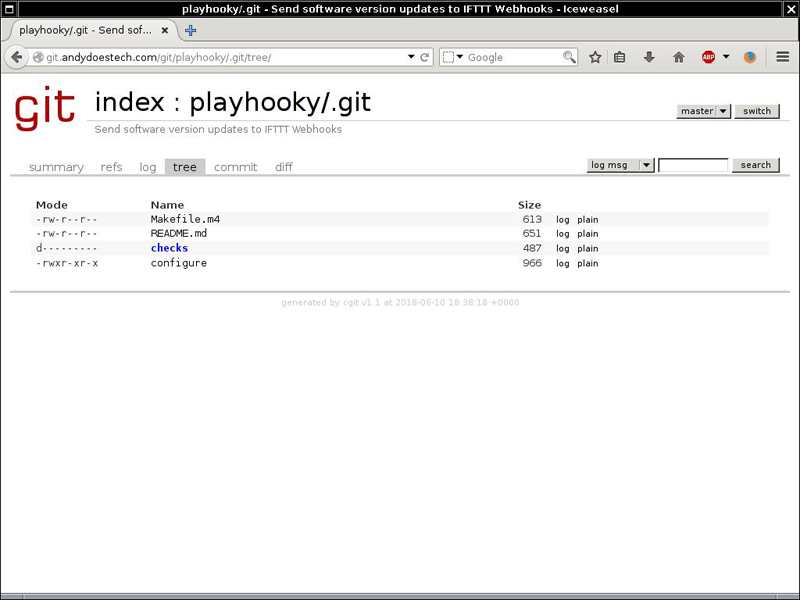

I'm not covering here.) After making this change to the cgitrc file, a listing

of repositories will be on the page. You can access the contents of the repository

by clicking on a repository and then clicking the "Tree" link at the

top of the page.

Figure 1. cgit Tree

Now that the environment is completely set up with repositories in place, you'll need to do some basic operations, such as clone, push and pull repositories from the server. As described previously, you'll use two main protocols to perform these basic git operations: HTTP and SSH.

In this environment, these protocols will serve two distinct purposes. HTTP will provide read-only access to repositories, which is useful for public access to repositories. You can obtain the HTTP clone URLs from the cgit repository listing page, and they will have the following form:

http://<HOSTNAME>/git/<REPOSITORY>/.git/.

For read-write access, you can clone repositories via SSH using a valid local user. A good practice might be to provide read-write access to a group and give that group recursive access to the /opt/repos directory.

The format of the SSH clone address is:

ssh://USER@HOSTNAME:PORT/opt/repos/<REPOSITORY>/

If the port used by SSH is left as the default port 22, you can omit

PORT

from the clone address. Note you may need to open firewall ports

in order for remote SSH and HTTP connections to be possible.

Your self-hosted minimalist Git environment is now complete. Although it may lack some of the advanced features provided by other solutions, it provides the basic functionality to manage distributed code. It's worth noting that you can expand the features of this environment far beyond what I've described here with little impact on performance and overall complexity.

Andy Carlson has worked in IT for the past 15 years doing networking and server administration along with occasional coding. He is thankful to have chosen a career that he loves, grows in and learns from. He currently resides in Cincinnati, Ohio, with his wife, three daughters and his son. His family is currently in the process of adopting two children internationally. He enjoys playing the guitar, coding, and spending time with family and friends.