Siri, Alexa and Google Home can all translate voice commands into basic activities, especially if those activities involve nothing more than sharing digital files like music and movies. Integration with home automation is also possible, though perhaps not as simply as users might desire—at least, not yet.

Still, the idea of converting voice commands into actions is intriguing to the maker world. The offerings from the big three seem like magic in a box, but we all know it's just software and hardware. No magic here. If that's the case, one might ask how anyone could build magic boxes?

It turns out that, using only one online API and a number of freely available libraries, the process is not as complex as it might seem. This article covers the Jarvis project, a Java application for capturing audio, translating to text, extracting and executing commands and vocally responding to the user. It also explores the programming issues related to integrating these components for programmed results. That means there is no machine learning or neural networks involved. The end goal is to have a selection of key words cause a specific method to be called to perform an action.

Jarvis started life several years ago as an experiment to see if voice control was possible in a DIY project. The first step was to determine what open-source support already existed. A couple weeks of research uncovered a number of possible projects in a variety of languages. This research is documented in a text document included in the docs/notes.txt file in the source repository. The final choice of a programming language was based on the selection of both a speech-to-text API and a natural language processor library.

Since Jarvis was experimental (it has since graduated to a tool in the IronMan project), it started with a requirement that it be as easy as possible to get working. Audio acquisition in Java is very straightforward and a bit simpler to use than in C or other languages. More important, once audio is collected, an API for converting it to text would be needed. The easiest API found for this was Google's Cloud Speech REST API. Since both audio collection and REST interfaces are fairly easy to handle in Java, it seemed that would be the likely choice of programming language for the project.

After audio was converted to text, the next step would be some kind of text analysis. That analysis is known as Natural Language Processing. The Apache OpenNLP library does just that, making it simple to break a text string into its component parts of speech. Since this was also a Java library, the selection of Java as the project language was complete.

Initially, the use of Google APIs included non-public interfaces—basically using interfaces hidden inside the Chrome browser. Those interfaces went away and were replaced by the current public Google Cloud Speech API. Additionally, Google's Translate text-to-speech feature was used, but that interface was removed after it was abused by the public. So an alternative solution was recently integrated: espeak-ng. Espeak is a command-line tool for speech synthesis. It can be integrated with voices from the mbrola project to help produce better (at least less computer-ish) voices. Think of it as an improved Stephen Hawking voice. Most important, espeak can be called directly from Java to generate audio files that Java then can play using the host's audio system.

With a set of APIs, tools and libraries in hand, it is now possible to design a program flow. Jarvis utilizes the following execution threads:

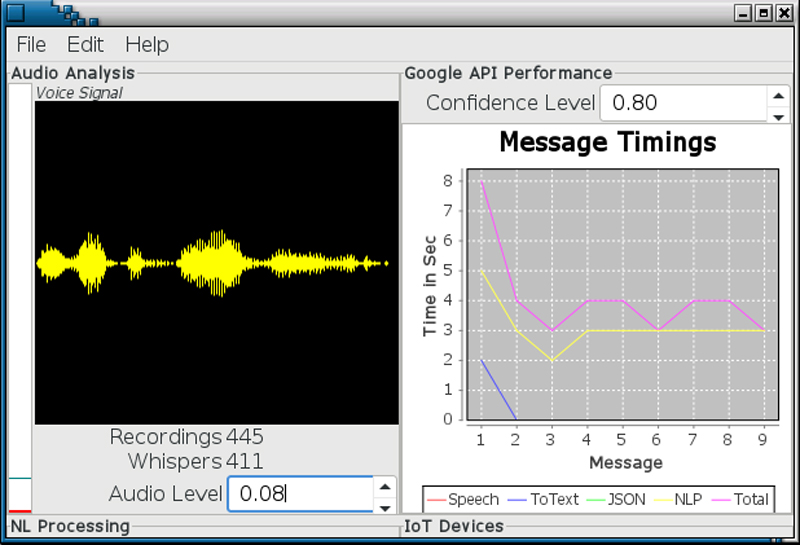

Jarvis also includes a simple UI, mostly for debugging purposes, which can graph thread processing times and show voice patterns. Each thread operates with a short delay loop that checks for inbound messages from other threads. The recording thread looks for audio above a configured level that is then saved to file when the level drops below a threshold value. This causes a message to be passed to the next thread for continued processing and so on. Even the UI thread is messaged with telemetry data to display.

Figure 1. Jarvis' UI is primarily for monitoring processes and not directly for user interaction.

In order to use Jarvis, you will need a microphone and some speakers. The PulseAudio Plugin was used in testing because it allows enabling and disabling of the input source, which means I don't have the audio input device enabled all the time. No sense letting hackers hear my every move, should they get that far into my world.

Any microphone can be used, but for long-range development plans, where audio should be picked up no matter where I am in a room, I picked up a Blue Snowball iCE Condenser Microphone. This is good quality for podcasts, and it does a fair job of picking up a clean recording of my voice anywhere in the room as long as I speak a little loud.

Speakers are necessary only if you want to hear Jarvis' responses. If you don't have any speakers for your computer, it won't prevent Jarvis from otherwise processing your voice commands.

Java provides support for reading from Linux audio subsystems through the

javax.sound.sampled.DataLine and

javax.sound.sampled.AudioSystem classes.

The first step in using these is to set up an AudioFormat class with the

required sample rate and associated configuration:

AudioFormat getAudioFormat() {

float sampleRate = 16000.0F;

int sampleSizeInBits = 16;

int channels = 1;

boolean signed = true;

boolean bigEndian = false;

return new AudioFormat(sampleRate, sampleSizeInBits,

↪channels, signed, bigEndian);

}

These settings are used later to determine the threshold level for

sampling audio. DataLine is then passed this class to set up buffering

audio data from the Linux audio subsystem. AudioSystem uses

DataLine

to get a Line object, which is the connection to the actual audio:

audioFormat = getAudioFormat();

DataLine.Info dataLineInfo = new DataLine.Info(

↪TargetDataLine.class, audioFormat);

line = (TargetDataLine) AudioSystem.getLine(dataLineInfo);

The line object is then opened, starting Java sampling of audio data. The line's buffer is tested for content, and if any is found, the audio level for that buffer is calculated. If the level is above a hard-coded threshold, audio recording is started. Recording writes the audio buffer to a stream buffer. When the level drops below the threshold, the recording is stopped, and the output stream is closed. This is called a snippet. If the snippet size is non-zero, you queue it for conversion to a WAV format using javaFLACEncoder:

int count = line.read(buffer, 0, buffer.length);

if ( count != 0 )

{

float level = calculateLevel(buffer,0,0);

if ( !recording )

{

if ( level >= threshold )

recording++;

}

else

{

if ( level < threshold )

{

recording=0;

Snippet snippet = new Snippet();

snippet.setBytes( out.toByteArray() );

if ( snippet.size() != 0 )

snippets.add( snippet );

}

}

Calculating the threshold requires running the length of the audio buffer to find a max integer value. Then the max value is normalized from 0.0 to 1.0, a percentage of the maximum volume. The percentage is used to compare against the threshold level. The encoded WAV file is then queued for conversion to text.

Converting the audio file to text requires passing it through Google's Cloud Speech API, a REST API that requires an API key and has a financial cost, albeit a very low one (practically zero) for the average Jarvis user. Jarvis is designed to allow users to utilize their own key as one is not provided in the source code.

Google's API requires passing the audio file as Base64-encoded data in a JSON object in the body of an HTTP message, where the destination URL is the REST API. The return data is also a JSON object, filled with the converted text and additional data. Jarvis uses a custom class, GAPI, to hold the returned text data and handles JSON parsing to extract fields for use by other classes. The SimpleJSON library is used for all JSON manipulation:

Path path = Paths.get( audiofile.getPath() );

byte[] data = Base64.getEncoder().encode( Files.readAllBytes(path) );

audiofile.delete();

if ( (data != null) || (data.length.0) )

{

String request = "https://speech.googleapis.com/v"

↪+ Cli.get(Cli.S_GAPIV) + "/speech:recognize?key=" + apikey;

JSONObject config = new JSONObject();

JSONObject audio = new JSONObject();

JSONObject parent = new JSONObject();

config.put("encoding","FLAC");

config.put("sampleRateHertz", new Integer(16000));

config.put("languageCode", "en-US");

audio.put("content", new String(data));

parent.put("config", config);

parent.put("audio", audio);

...use HttpURLConnection to POST the message...

...get response with a BufferedReader object...

...queue text from response for command processing...

}

Command processing forwards the text response to a GAPI object to determine what comes next. If Google found recognizable text, it is queued for conversion into parts of speech by the Apache OpenNLP library via Jarvis' NLP class. This tokenizes the text into collections of verbs, nouns, names and so forth. The NLP class is used to identify whether the command was intended for Jarvis (it must have contained that name):

private boolean forJarvis(NLP nlp)

{

String[] words = nlp.getNames();

if ( words == null )

return false;

for(int i=0; i<words.length; i++)

{

if ( words[i].equalsIgnoreCase("jarvis") )

return true;

}

words = nlp.getNoun();

if ( words == null )

return false;

for(int i=0; i<words.length; i++)

{

if ( words[i].equalsIgnoreCase("jarvis") )

return true;

}

return false;

}

Requests meant for Jarvis are searched for key words in various formats

and ordering to identify a command. The following code is used to respond

to "Are you there", "Are you awake", "Do you hear me" or "Can you hear

me" commands. The Java String matches() method is used to glob related

keywords, making it easier to find variations on a command:

private boolean isAwake(NLP nlp)

{

int i=0;

String[] token = nlp.getTokens();

boolean toJarvis = false;

String[] tag = nlp.getTags();

if ( tag != null )

{

String words = "are|do|can";

for(i=1; i<tag.length; i++)

{

if ( tag[i].startsWith("PR") )

{

if ( token[i].equalsIgnoreCase("you") )

{

if ( token[i-1].toLowerCase().

↪matches("("+words+")") )

{

toJarvis = true;

break;

}

}

}

}

}

if ( !toJarvis )

return false;

token = nlp.getVerbs();

if ( token != null )

{

String words = "listen|hear";

for(i=0; i<token.length; i++)

{

if ( token[i].toLowerCase()

↪.matches("("+words+").*") )

return true;

}

}

token = nlp.getAdverbs();

if ( token != null )

{

String words = "awake|there";

for(i=0; i<token.length; i++)

{

if ( token[i].toLowerCase()

↪.matches("("+words+").*") )

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

Once a command is found, it can be turned into an action. This part of Jarvis is still evolving, but the intent will be to use a REST API to contact a PiBox server with the command. The PiBox server will be responsible for contacting IoT devices like light switches or window shades to perform the appropriate action.

This type of programmed response is highly inefficient. Sequential processing of commands is slow and will only get worse with more commands. However, it serves as a reasonable implementation for simple support of home-automation commands.

After the action is processed (or queued on the remote PiBox server for

handling), a vocalized response can be queued. In the above example, the

response is "Yes, I'm here. Can I help you?" This text is placed in one

of Jarvis' internal Message objects to be queued on the Speaker thread.

Text is extracted from the Message object, and a command line is built

using the espeak-ng utility. Espeak is a package you can install from your Linux distribution package management system. On Fedora, the

command is:

sudo dnf install espeak-ng

Note that there is the original espeak and the rebooted

espeak-ng.

They seem to produce the same results for Jarvis and have the same

command name (espeak), so either should work.

The espeak program takes text as input and outputs an audio file.

That file is then read and played using Java's sound support:

String cmd = "espeak-ng -z -k40 -l1 -g0.8 -p 78 -s 215 -v mb-us1

↪-f " + messageFilename + " -w " + audioFilename;

Utils.runCmd(cmd);

file = new File(audioFilename);

InputStream in = new FileInputStream(audioFilename);

AudioStream audioStream = new AudioStream(in);

AudioPlayer.player.start(audioStream);

file.delete();

In this example, the runCmd() method is a Jarvis wrapper around Java

process management to simplify running an external command.

Jarvis relies on Google's Cloud Speech API to convert audio files to text.

This API also requires an API key provided by Google. Since this service

is not free, Jarvis allows developers to place their own API key in

the docs directory and the build system will find it. Alternatively,

if you run Jarvis without rebuilding, just place the apikey in the

~/.jarvis directory.

This DIY system is not completely secure. The use of the Google Cloud Speech API implies the transfer of audio files across the internet to Google, which translates it to text. This means that Google has access to the audio, the converted text and the source of both. If you are concerned with privacy, be sure to consider this issue before using Jarvis.

The source code in this article is simplified from actual Jarvis code

for the sake of explanation only. Note that the Jarvis

source code, although written in Java, is not designed for building with

Maven or within Eclipse. The build system has been crafted manually and

is intended to be run from the command line with Ant. Use ant

jarvis

to build, ant jarvis.run to run from the build artifacts and

ant rpm

to generate an RPM file if used on Fedora, Red Hat or CentOS systems. See

ant -p for a list of supported targets. Also note that

Jarvis is a Java program written by a C developer. Caveat programmer.

Command processing in Jarvis is programmed, which means there is no AI here. Commands are parsed from text and grouped loosely to allow for variations in commands, such as "are you", "can you" and "do you" all referring to the same command processing track.

This mechanism should be expanded to support a configuration language so that commands can be extended without having to rewrite and extend the code or recompile. Ideas related to this are being considered currently but no design or implementation has started.

Taking Jarvis beyond mere programmed responses requires integration with an AI back end. The TensorFlow project from Google offers a Java API and is a logical next step. However, for basic home automation, the integration of AI is a bit of over-engineering. There currently are no plans for TensorFlow or other AI integration in Jarvis.

Jarvis is still just an experiment and has plenty of limitations. Message flow through a series of threads slows processing significantly and shows up as delays in responses and actions. Still, Jarvis' future is bright in my home. The IronMan project will integrate Jarvis with a PiBox server for distributing commands to IoT devices. Soon, I'll be able to walk into my office and say "Lights on, Jarvis". And that's a very bright idea, indeed.