curses to draw to the terminal screen. By Jim HallWhile graphical user interfaces are very cool, not every program needs to run with a point-and-click interface. For example, the venerable vi editor ran in plain-text terminals long before the first GUI.

The vi editor is one example of a screen-oriented program that draws in "text" mode, using a library called curses, which provides a set of programming interfaces to manipulate the terminal screen. The curses library originated in BSD UNIX, but Linux systems provide this functionality through the ncurses library.

[For a "blast from the past" on ncurses, see "ncurses: Portable Screen-Handling for Linux", September 1, 1995, by Eric S. Raymond.]

Creating programs that use curses is actually quite simple. In this article, I show an example program that leverages curses to draw to the terminal screen.

One simple way to demonstrate a few curses functions is by generating Sierpinski's Triangle. If you aren't familiar with this method to generate Sierpinski's Triangle, here are the rules:

Then:

So with those instructions, I wrote this program to draw Sierpinski's Triangle to the terminal screen using the curses functions:

1 /* triangle.c */

2

3 #include <curses.h>

4 #include <stdlib.h>

5

6 #include "getrandom_int.h"

7

8 #define ITERMAX 10000

9

10 int main(void)

11 {

12 long iter;

13 int yi, xi;

14 int y[3], x[3];

15 int index;

16 int maxlines, maxcols;

17

18 /* initialize curses */

19

20 initscr();

21 cbreak();

22 noecho();

23

24 clear();

25

26 /* initialize triangle */

27

28 maxlines = LINES - 1;

29 maxcols = COLS - 1;

30

31 y[0] = 0;

32 x[0] = 0;

33

34 y[1] = maxlines;

35 x[1] = maxcols / 2;

36

37 y[2] = 0;

38 x[2] = maxcols;

39

40 mvaddch(y[0], x[0], '0');

41 mvaddch(y[1], x[1], '1');

42 mvaddch(y[2], x[2], '2');

43

44 /* initialize yi,xi with random values */

45

46 yi = getrandom_int() % maxlines;

47 xi = getrandom_int() % maxcols;

48

49 mvaddch(yi, xi, '.');

50

51 /* iterate the triangle */

52

53 for (iter = 0; iter < ITERMAX; iter++) {

54 index = getrandom_int() % 3;

55

56 yi = (yi + y[index]) / 2;

57 xi = (xi + x[index]) / 2;

58

59 mvaddch(yi, xi, '*');

60 refresh();

61 }

62

63 /* done */

64

65 mvaddstr(maxlines, 0, "Press any key to quit");

66

67 refresh();

68

69 getch();

70 endwin();

71

72 exit(0);

73 }

Let me walk through that program by way of explanation. First, the getrandom_int() is my own wrapper to the Linux getrandom() system call, but it's guaranteed to return a positive integer value. Otherwise, you should be able to identify the code lines that initialize and then iterate Sierpinski's Triangle, based on the above rules. Aside from that, let's look at the curses functions I used to draw the triangle on a terminal.

Most curses programs will start with these four instructions. 1) The initscr() function determines the terminal type, including its size and features, and sets up the curses environment based on what the terminal can support. The cbreak() function disables line buffering and sets curses to take one character at a time. The noecho() function tells curses not to echo the input back to the screen, and the clear() function clears the screen:

20 initscr();

21 cbreak();

22 noecho();

23

24 clear();

The program then sets a few variables to define the three points that define a triangle. Note the use of LINES and COLS here, which were set by initscr(). These values tell the program how many lines and columns exist on the terminal. Screen coordinates start at zero, so the top-left of the screen is row 0, column 0. The bottom-right of the screen is row LINES - 1, column COLS - 1. To make this easy to remember, my program sets these values in the variables maxlines and maxcols, respectively.

Two simple methods to draw text on the screen are the addch() and addstr() functions. To put text at a specific screen location, use the related mvaddch() and mvaddstr() functions. My program uses these functions in several places. First, the program draws the three points that define the triangle, labeled "0", "1" and "2":

40 mvaddch(y[0], x[0], '0');

41 mvaddch(y[1], x[1], '1');

42 mvaddch(y[2], x[2], '2');

To draw the random starting point, the program makes a similar call:

49 mvaddch(yi, xi, '.');

And to draw each successive point in Sierpinski's Triangle iteration:

59 mvaddch(yi, xi, '*');

When the program is done, it displays a helpful message at the lower-left corner of the screen (at row maxlines, column 0):

65 mvaddstr(maxlines, 0, "Press any key to quit");

It's important to note that curses maintains a version of the screen in memory and updates the screen only when you ask it to. This provides greater performance, especially if you want to display a lot of text to the screen. This is because curses can update only those parts of the screen that changed since the last update. To cause curses to update the terminal screen, use the refresh() function.

In my example program, I've chosen to update the screen after "drawing" each successive point in Sierpinski's Triangle. By doing so, users should be able to observe each iteration in the triangle.

Before exiting, I use the getch() function to wait for the user to press a key. Then I call endwin() to exit the curses environment and return the terminal screen to normal control:

69 getch();

70 endwin();

Now that you have your first sample curses program, it's time to compile and run it. Remember that Linux systems implement the curses functionality via the ncurses library, so you need to link with -lncurses when you compile—for example:

$ ls

getrandom_int.c getrandom_int.h triangle.c

$ gcc -Wall -lncurses -o triangle triangle.c getrandom_int.c

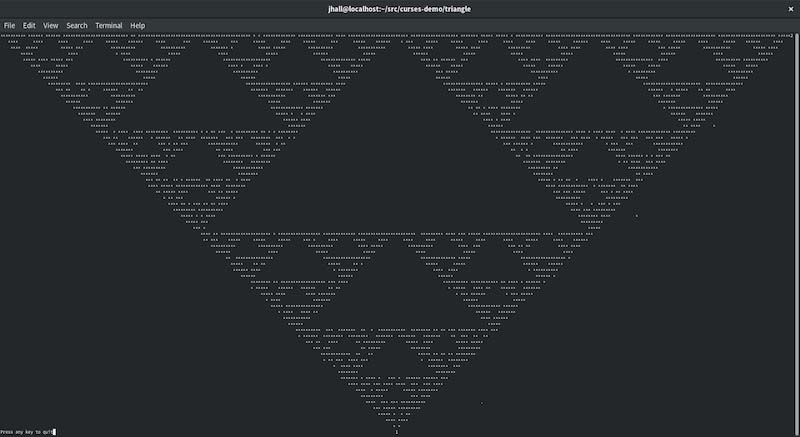

Running the triangle program on a standard 80x24 terminal is not very interesting. You just can't see much detail in Sierpinski's Triangle at that resolution. If you run a terminal window and set a very small font size, you can see the fractal nature of Sierpinski's Triangle more easily. On my system, the output looks like Figure 1.

Figure 1. Output of the triangle Program

Despite the random nature of the iteration, every run of Sierpinski's Triangle will look pretty much the same. The only difference will be where the first few points are drawn to the screen. In this example, you can see the single dot that starts the triangle, near point 1. It looks like the program picked point 2 next, and you can see the asterisk halfway between the dot and the "2". And it looks like the program randomly picked point 2 for the next random number, because you can see the asterisk halfway between the first asterisk and the "2". From there, it's impossible to tell how the triangle was drawn, because all of the successive dots fall within the triangle area.

This program is a simple example of how to use the curses functions to draw characters to the screen. You can do so much more with curses, depending on what you need your program to do. In a follow up article, I will show how to use curses to allow the user to interact with the screen. If you are interested in getting a head start with curses, I encourage you to read Pradeep Padala's "NCURSES Programming HOWTO", at the Linux Documentation Project.