With the demise of the big kernel lock (BKL), various new locks have taken its place to cover various types of situations, some more rarefied than others. Recently Waiman Long implemented the TO futex (throughput-optimized futex), which prioritizes throughput over giving all processes a fair chance to claim the lock.

It's a strange concept—usually a UNIX-based system would make fairness to all users the highest priority. But the TO futex outperformed wait-wake futexes and priority-inheritance futexes on certain workloads, specifically those involving short, critical sections of code, with large numbers of threads competing for the same lock.

Sometimes, as Thomas Gleixner pointed out, it can be hard for developers to know which futex to choose, given so many options and each with such specific optimal use patterns, although Waiman has said he feels the TO futex may simply outperform the others well enough to be the preferred choice almost all the time.

It's hard to know for sure. We can assume that the many-eyes principle of open-source development implies that eventually any poor locking choice will be found and fixed. So maybe the added complexity will simply come out in the wash. On the other hand, there's a real benefit in developers actually being able to understand what they're doing when they modify kernel code. So, keeping Linux locking simple may turn out to be preferable in the end.

Sometimes kernel developers will turn their attention to corner cases and pathological conditions, trying to smooth out behaviors that rarely if ever occur.

Al Viro gave that a shot recently, when he noticed that the writev() system call seemed to behave unintuitively when fed certain kinds of bad input. The writev() call writes a series of memory buffers to a file. But if one of the middle buffers is given an undefined address in the input, writev() still would write the first portion of data before giving up.

He felt this was a mistake. Instead of writing just a portion of the data—essentially creating an unpredictable state via behaviors that developers should definitely not rely on—he felt that no data (or at least a predictable amount of data) should be written, and the call should return the EFAULT error code.

When it comes to system calls, however, you can't just do whatever you want. There are various standards, specifically POSIX, that you either have to obey or have a good reason not to.

In this case, Al felt that POSIX was vague enough to let his preferred behavior sail through. As he understood the standard, the exact amount of data written when the error occurred was actually variable. And, that being the case, he figured why not just make the logic be “if some addresses in the buffer(s) we are asked to write are invalid, the write will be shortened by up to a PAGE_SIZE from the first such invalid address”.

Linus Torvalds approved this arrangement, but Alan Cox objected. He noted that POSIX version 1003.1 said “Each iovec entry specifies the base address and length of an area in memory from which data should be written. The writev() function shall always write a complete area before proceeding to the next.”

So, instead of shortening the write by up to PAGE_SIZE, Alan's reading of the standard required writing the whole amount of data and then failing on the upcoming invalid address.

But, Alan pointed out that passing an invalid address to writev() was not anything anyone would want to do and didn't have any clearly defined consequence. He felt it would be more useful to think about how to deal with realistic causes of writev() being passed an invalid address—for example, when the system ran out of disk space in the midst of the writev() call.

Linus felt that the disk-full scenario was a reasonable situation to care about. But, he also felt that the main point of the POSIX behavior—either expressed or implied—was to prevent weird situations where users could see later writes without being able to see earlier ones. He felt it was important to ensure that “you cannot do some fancy threaded thing where you do different iovec parts concurrently, because that could be seen by a reader (or more likely mmap) as doing the writes out of order.”

It's unclear which behavior might ultimately get into the kernel. These debates often pull from bizarre sources. For example, it could turn out that there's some kind of security issue with one or the other position on the issue, in which case whichever position successfully addressed the security concern would be the winner.

Luis R. Rodriguez tried to fix a possible race condition by having userspace recognize a given situation and alert the kernel. Not surprisingly, it was met with a strong rebuke from Linus Torvalds.

The race condition occurred if the user tried to read a file from the system's filesystem during bootup. If the read occurred at one time, the filesystem would be unavailable, but if the read occurred slightly later, it would.

The problem, as he saw it, was that only userspace could know whether certain filesystems already had been mounted. The obvious solution, he felt, was for userspace to alert the kernel to the filesystem availability, so the kernel could attempt to access the needed file only after that file was actually on a mounted filesystem.

Linus called this a “horrible hack” and a white flag of surrender. Not only that, but he said “it's broken nasty crap with a user interface, so we'll be stuck with it forever.”

He suggested instead that any drivers running into this problem simply be fixed to not do that. But, Dmitry Torokhov didn't see how that could be accomplished. He said:

Some devices do need to have firmware loaded so we know their capabilities, so we really can't push the firmware loading into “open”....These devices we want to probe asynchronously and simply tell the firmware loader to wait for firmware to become available. The problem is we do not know when to give up, since we do not know where the firmware might be. But userspace knows and can tell us.

And, Bjorn Andersson piled on, saying there were actual real-world cases that would benefit from Luis' code.

But, Linus saw the entire concept as too broken to salvage, regardless of any use value it might have. He would rather bundle firmware directly into a kernel module, he said, than have the kernel depend on a userspace notification.

The whole discussion was useful mostly as an example of how kernel developers can stand up under scathing critiques from Linus and still pull useful technical feedback out of what he says. In this case, he left no room for doubt—alerts coming from userspace to the kernel would not be allowed under any circumstances.

I do a lot of system administration with my thumbs. Yes, if I'm home, I grab a laptop or go to my office and type in a real terminal window. Usually, when things go wrong though, I'm at my daughters' volleyball match or shopping with my wife. Thankfully, most tasks can be done remotely via SSH. There are lots of SSH clients for Android, but my favorite is JuiceSSH.

Yes, part of my love for the app is that it has a cool icon in the shape of a lemon, but really, there's more to it than that. It has a plugin architecture that allows you to build functionality on top of SSH. It also allows you to execute code snippets on multiple connections with a click of a button.

They keyboard is designed in such a way that even vi users like myself can manage to edit files remotely. And thanks to the ability to import private SSH keys, I can connect to those servers where I have password authentication disabled. (For example, most cloud servers don't allow you to log in via password, they require you to use SSH keys, which is awesome.)

To be honest, I do so much work remotely with my phone, that I'm considering getting a foldable Bluetooth keyboard so I can actually do some typing in a pinch if needed. If I find a keyboard I like, I'll be sure to write about it in a future issue! You can get JuiceSSH from the Google Play Store.

In the past, if you wanted a friendly environment for doing Python programming, you would use Ipython. The Ipython project actually consists of three parts: the standard console interface, a Qt-based GUI interface and a web server interface that you can connect to with a web browser. The web browser interface, especially, has become the de facto way of doing scientific programming with Python. It has become so popular in fact, it has spun off as its own project, named Jupyter. In this article, I take a look at how to get the latest version up and running, and I discuss the kinds of things you can do with it once it is set up.

The first step is to install the latest version. Because it is under very active development, you probably will want to keep it updated on your system. pip is definitely the easiest way to do this. The following command will install Jupyter, if it isn't already installed, or it will update Jupyter to the latest version:

sudo pip install --upgrade jupyter

Be sure that you have a C compiler installed, along with the development package for Python. For example, on Debian-based systems, you can be sure you are ready by executing the following command:

sudo apt-get install python-dev build-essentials

This should make sure you have everything you need installed.

To start Jupyter, open a terminal window and enter the command:

jupyter notebook --no-browser

This will start a web server, listening on port 8888, that will accept connections from the local machine. For security reasons, by default, it will ignore incoming connections from outside machines. If you want to set it up to accept connections from outside machines, you can do so by adding an extra option:

jupyter notebook --no-browser --ip=*

This makes your Jupyter server wide open, so it is strongly discouraged unless you are on a secure private network. Otherwise, you should have some sort of user authentication set up to manage who can use your system.

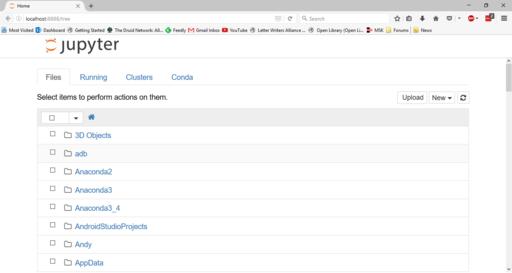

Once Jupyter is up and running, open a browser and point it to http://localhost:8888. Across the top, you will see a series of tabs for each section of the workspace. Most people will see only three: Files, Running and Clusters. If you are using the Anaconda Python distribution, you will get a fourth tab named Conda.

Figure 1. When you first enter Jupyter, you are presented with a file listing from the current working directory.

On startup, you will be located at the first tab, Files. This is simply a directory listing of the current working directory. You probably won't have any notebooks currently available, so you will need to create a new one. You can do that by clicking the drop-down list on the right-hand side of the screen labeled New and selecting the Python notebook entry on the menu. This will open a new browser tab and load a new empty notebook.

The second tab shows you all of the active notebooks running on this particular server. You can click the related link to open the selected notebook in a new browser tab or click the Shutdown button to halt the selected notebook. There is also a section for any active terminal sessions. The Clusters section gives you status information on the parallel Python engines that are configured on your system. By default, this isn't configured at all.

If you are using Anaconda, you will get a fourth section labeled Conda. This section gives you details about what packages are available and what packages are installed. You even can manage your Conda environments, creating new ones, exporting existing ones or deleting environments that you are done with.

Let's take a look at what you can do with the notebook itself. The interface should feel familiar to people who have used applications like Maple or Mathematica. Your input is entered in sections called cells. Cells can be of different types, namely code, markdown text or headings. This way, you can have text cells describing the code sections, explaining what the code is doing and why. It's extremely useful when you're doing scientific calculations, because it allows you to include your documentation with your code, so everything stays synchronized and up to date.

When you start entering lines of code, pressing Enter takes you to a new line within the same cell. None of the code gets executed yet. When you are ready to run the cell, press the Shift and Enter keys together. All of the code runs within the same Python engine, so results from one cell will be available to other cells later on.

You also can import extra Python modules, just like you do in any other Python environment. The most useful for visualizing data and results is matplotlib. If you import the matplotlib module and execute plotting commands, Jupyter can render the resulting graphs directly in the notebook.

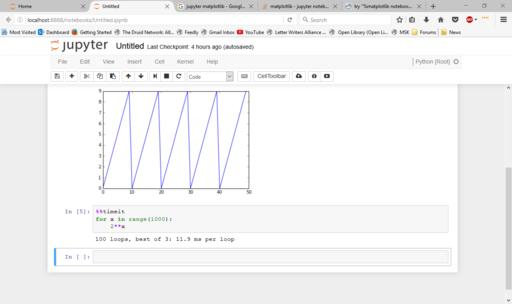

As you can see, you need to use an extra statement that starts with a % character to tell Jupyter to render the plot as an image within the notebook. Otherwise, the plots will be rendered within a new window. This new statement is called a magic. There is an entire library of magics available. For example, you can use the timeit magic to profile how long it takes to run the code within a cell.

Figure 7. There are several magic statements available, such as the timeit magic to find runtimes of code cells.

If it is a section of code that has a short runtime, Jupyter automatically will run it several times to get an average runtime. This allows you to work on optimizing your code as well as developing it.

When you are ready to share your results, several different options are available. You always can simply share the Jupyter notebook. It is all stored in a single file with the filename ending .ipynb. The other options depend a bit on which Python modules you have installed on your system. The formats most often used are either as a single static HTML page or PDF document. If you are going to present your results, you even can export it as an HTML-based presentation where the cells are formatted as individual slides. All of these options are available under the File→Download As menu item.

Hopefully this article has shown some functionality you can make use of in your own code. Jupyter is especially useful for scientific exploration. You can try lots of different calculations and do different types of data analysis and see the results right away within the notebook. And when you reach a useful conclusion, you can share the notebook with others within the growing community of Jupyter users.

Slack is an incredible communication tool for groups of any size (see my piece on it in the November 2016 issue). At the company I work for during the day, Slack has become more widely used than email or instant messaging. It truly has become the hub of company communication. So rather than have my servers send email, I've turned to Slack for delivering information to my users. Thankfully, Slack is extremely open to adding applications and integrations.

The simplest integration is called an “incoming webhook”, and it delivers messages to Slack channels (or individual users) by sending a POST to a specially formed URL. The first step is to find the custom integration area in Slack, which isn't as clear as I'd like. On the website, click on your Slack group name at the top left, and pick “Apps & Integrations” from the drop-down menu. Then on the apps page, click “build” on the upper right. Finally, click “Make a Custom Integration” and select “incoming webhooks”.

From there it's a matter of selecting where you want the notification to post, what icon to give it, what name to assign to your bot and so on. Once it's saved, you can use curl to post a message to your unique URL (which is on the creation page, be sure to copy it to your clipboard):

curl -X POST --data "payload={"text": "Cool Message"}"

↪https://hooks.slack.com/services/YOURAPI/CODEHERE/TOPOST

That's it! You can create a BASH script to make the process simple and integrate the notification system into your server scripts!

Computer folks are known for their mass consumption of caffeinated beverages. Some prefer coffee; some prefer tea. (Some drink energy drinks too, but we won't talk about those folks.) I actually go between coffee and tea depending on the season. During the summer, I drink mainly coffee. It can be freshly ground brewed coffee, a fancy coffee made with my espresso machine or even a quick K-cup abomination at 6am. But once fall sets in and the snow starts falling, I always switch to tea. I'm not sure why, but for me, the winter means tea.

Why would I mention my preferences in a tech magazine? Because if you're like me and drink tea, either seasonally or exclusively, you know it can be a pain. Sure there are teabags for people who don't care what their tea tastes like, but I prefer loose-leaf tea. And, it can be a pain to make. A couple years back I discovered the Adagio ingenuiTEA steeping device. It makes loose-leaf tea actually easier than teabags. You simply put the loose tea in the top, poor hot water directly on the leaves, and then after steeping, you let it drain through the filter into your cup.

Through the years, I've purchased several brands of the tea steepers (my current favorite is the Teaze Tea Infuser), and they all work in a similar manner. It's amazing how often I use my Teaze device, even when I have a $250 Breville Perfect Tea maker on my office shelf. I still go to the $15 device 95% of the time! It may seem like an odd recommendation for a tech magazine, but anyone in the tech industry knows that a proper beverage is as important as a proper operating system, so check one out today. If you search for “ingenuitea” on Amazon, you'll see a bunch of different brands. They're cheap, and awesome. In fact, it might be the first time I've ever given a non-tech-related item the Editors' Choice award, but if you like tea, I urge you to give it a try.

“In the right light, at the right time, everything is extraordinary.”

—Aaron Rose

There is no Them, there is only Us. Some of Us think this or some of Us think that, but we're all Us.

—Lisa Williams

I think people don't place a high enough value on how much they are nurtured by doing whatever it is that totally absorbs them.

—Jean Shinoda Bolen

He that will not sail until all dangers are over, will never put to sea.

—Thomas Fuller

In an industrial society which confuses work and productivity, the necessity of producing has always been an enemy of the desire to create.

—Raoul Vaneigem

I listen to a lot of audiobooks. They're not the sort of thing you blast from your car speakers, because invariably when you pull up to a drive-thru window, it's at an awkward part of the book. Thankfully I don't read many books with sex scenes, but it's a bit embarrassing when it's a super-cheesy-sounding part of the book that plays while you're paying. But, I digress.

I don't like earbuds or headphones, because I prefer to hear what's going on around me. So when I'm driving, or walking with someone, I tend to leave one earbud in, and the other out. It's not perfect, but it works.

Recently, however, I discovered bone-conduction headphones. I really like the Trekz Titanium model (https://aftershokz.com/products/trekz-titanium), but they're fairly pricey, and others might work just as well.

The concept is that instead of putting something in your ears, the device vibrates the bones in your head, which in turn vibrate your inner ears and produce sound. It means your ears are completely open, so you can hear people talking to you or honking behind you. Thanks to the sound transferring internally, however, you still can hear the audio really well too. In fact, if you want to drown out the outside world, you can put earplugs in and totally immerse yourself in audio. It feels weird to increase the volume by plugging your ears, but it works. In fact, if you want to try it, just hum, and while you're humming, plug your ears. That same sort of thing happens with bone conduction headsets. It's sort of magical.

Like I said, I use Trekz brand and really like them. I can take calls, listen to music or play/pause my audiobooks with ease. If you like the privacy of earbuds, but don't want to stick anything in your ears, give bone conduction a try. I thought it was a gimmick, but I'm happy to say I was wrong!