The NMI (non-masking interrupt) system in Linux has been a notorious patchwork for a long time, and Andy Lutomirski recently decided to try to clean it up. NMIs occur when something's wrong with the hardware underlying a running system. Typically in those cases, the NMI attempts to preserve user data and get the system into as orderly a state as possible, before an inevitable crash.

Andy felt that in the current NMI code, there were various corner cases and security holes that needed to be straightened out, but the way to go about doing so was not obvious. For example, sometimes an NMI could legitimately be triggered within another NMI, in which case the interrupt code would need to know that it had been called from “NMI context” rather than from regular kernel space. But, the best way to detect NMI context was not so easy to determine.

Also, Andy saw no way around a significant speed cost, if his goal were to account for all possible corner cases. On the other hand, allowing some relatively acceptable level of incorrectness would let the kernel blaze along at a fast clip. Should he focus on maximizing speed or guaranteeing correctness?

He submitted some patches, favoring the more correct approach, but this was actually shot down by Linus Torvalds. Linus wanted to favor speed over correctness if at all possible, which meant analyzing the specific problems that a less correct approach would introduce. Would any of them lead to real problems, or would the issues be largely ignorable?

As Linus put it, for example, there was one case where it was theoretically possible for bad code to loop over infinitely recursing NMIs, causing the stack to grow without bound. But, the code to do that would have no use whatsoever, so any code that did it would be buggy anyway. So, Linus saw no need for Andy's patches to guard against that possibility.

Going further, Linus said the simplest approach would be to disallow nested NMIs—this would save the trouble of having to guess whether code was in NMI context, and it would save all the other usual trouble associated with nesting call stacks.

Problem solved! Except, not really. Andy and others proved reluctant to go along with Linus' idea. Not because it would cause any problems within the kernel, but because it would require discarding certain breakpoints that might be encountered in the code. If the kernel discarded breakpoints needed by the GDB debugger, it would make GDB useless for debugging the kernel.

Andy dug a bit deeper into the code in an effort to come up with a way to avoid NMI recursion, while simultaneously avoiding disabling just those breakpoints needed by GDB. Finally, he came up with a solution that was acceptable to Linus: only in-kernel breakpoints would be discarded. User breakpoints, such as those set by the GDB user program, still could be kept.

The NMI code has been super thorny and messed up. But in general, it seems like more and more of the super-messed-up stuff is being addressed by kernel developers. The NMI code is a case in point. After years of fragility and inconsistency, it's on the verge of becoming much cleaner and more predictable.

The “If This Then That” site has been around for a long time, but if you haven't checked it out in a while, you owe it to yourself to do so. The Android app (which had a recent name change to simply “IF”) makes it easy to manipulate on the fly, and you're still able to interact with your account on its Web site. The beauty of IFTTT is its ability to work without any user interaction.

I have recipes set up that notify me when someone adds a file into a shared Dropbox folder, which is far more convenient than constantly checking manually. I also manage all my social network postings with IFTTT, so if I post a photo via Instagram or want to send a text update to Facebook and Twitter, all my social networking channels are updated. In fact, IFTTT even allows you to cross-post Instagram photos to Twitter and have them show up as native Twitter images.

If you're not using IFTTT to automate your life, you need to head over to ifttt.com and start now. If you're already using it, you should download the Android app, which has an incredible interface to the already awesome IFTTT back end. Get it at the Play Store today; just search for “IF” or “IFTTT”—either will find the app.

For my day job, I occasionally have to demonstrate concepts in a Windows environment. The most time-consuming part of the process is almost always the installation. Don't get me wrong; Linux takes a long time to install, but in order to set up a multi-system lab of Windows computers, it can take days!

Thankfully, the folks over at https://automatedlab.codeplex.com have created an open-source program that automatically will set up an entire lab of servers, including domain controllers, user accounts, trust relationships and all the other Windows things I tend to forget after going through the process manually. Because it's script-based, there are lots of pre-configured lab options ready to click and install. Whether you need a simple two-server lab or a complex farm with redundant domain controllers, Automated Lab can do the heavy lifting.

Although the tool is open source, the Microsoft licenses are not. You need to have the installation keys and ISO files in place before you can build the labs. Still, the amount of time and headaches you can save with Automated Lab makes it well worth the download and configuration, especially if you need to build test labs on a regular basis.

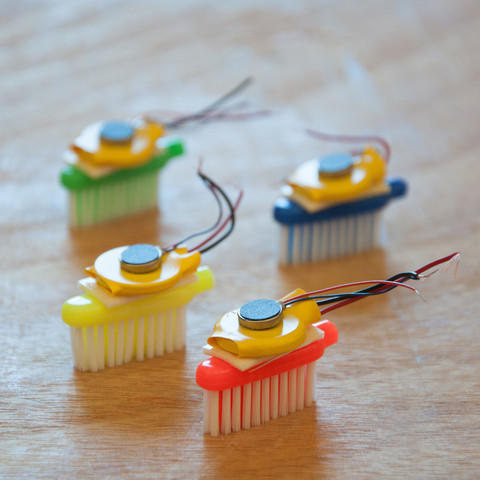

If you've ever dropped Mentos in a bottle of Coke with kids or grown your own rock candy in a jar with string, you know how excited children get when doing science. For some of us, that fascination never goes away, which is why things like Maker Faire exist. If you want your children (or someone else's children) to grow into awesome nerds, one of the best things you can do is get them involved with projects at www.makershed.com.

Although it's true that many of the kits you can purchase are a bit too advanced for kindergartners, there are plenty that are perfect for any age. You can head over to www.makershed.com/collections/beginner to see a bunch of pre-selected projects designed for beginners of all ages. All it takes is a dancing brush-bot or a handful of LED throwies to make kids fall in love with making things.

(Image via www.makershed.com)

Even if you don't purchase the kits from Maker Shed, I urge you to inspire the youngsters in your life into creating awesome things. If you guide them, they'll be less likely to do the sorts of things I did in my youth, like make a stun gun from an automobile ignition coil and take it to school to show my friends. Trust me, principals are far more impressed with an Altoid-tin phone charger for show and tell than with a duct-tape-mounted taser gun.

You can buy pre-made kits at www.makershed.com or visit sites like instructables.com for homemade ideas you can make yourself. In fact, doing cool projects with kids is such an awesome thing to do, it gets this month's Editors' Choice award. Giving an idea the award might seem like an odd thing to do, but who doesn't love science projects? We sure do!

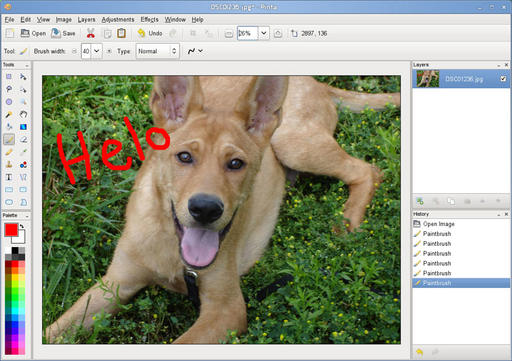

A while back I wrote about the awesome open-source image editing program Paint.NET, which is available only for Windows. Although I'm thrilled there is an open-source option for Windows users, Paint.NET is one of those apps that is so cool, I wish it worked in Linux! Thankfully, there's another app in town with similar features, and it's cross-platform!

Pinta isn't exactly a Paint.NET clone, but it looks and functions very much like the Windows-only image editor. It has simple controls, but they're powerful enough to do most of the simple image editing you need to do on a day-to-day basis. Whether you want to apply artistic filters, autocorrect color levels or just crop a former friend out of a group photo, Pinta has you covered.

(Image from www.pinta-project.com)

There certainly are more robust image editing options available for Linux, but often programs like GIMP are overkill for simple editing. Pinta is designed with the “less is more” mentality. It's available for Linux, OS X, Windows and even BSD, so there's no reason to avoid trying Pinta today. Check it out at www.pinta-project.com.

More and more journals are demanding that the science being published be reproducible. Ideally, if you publish your code, that should be enough for someone else to reproduce the results you are claiming. But, anyone who has done any actual computational science knows that this is not true. The number of times you twiddle bits of your code to test different hypotheses, or the specific bits of data you use to test your code and then to do your actual analysis, grows exponentially as you are going through your research program. It becomes very difficult to keep track of all of those changes and variations over time.

Because more and more scientific work is being done in Python, a new tool is available to help automate the recording of your research program. Recipy is a new Python module that you can use within your code development to manage the history of said code development.

Recipy exists in the Python module repository, so installation can be as easy as:

pip install recipy

The code resides in a GitHub repository, so you always can get the latest and greatest version by cloning the repository and installing it manually. If you do decide to install manually, you also can install the requirements with the following using the file from the recipy source code::

pip install -r requirements.txt

Once you have it installed, using it is extremely easy. You can alter your scripts by adding this line to the top of the file:

import recipy

It needs to be the very first line of Python executed in order to capture everything else that happens within your program. If you don't even want to alter your files that much, you can run your code through Recipy with the command:

python -m recipy my_script.py

All of the reporting data is stored within a TinyDB database, in a file named test.npy.

Once you have collected the details of your code, you now can start to play around with the results stored in the test.npy file. To explore this module, let's use the sample code from the recipy documentation. A short example is the following, saved in the file my_script.py:

import recipy

import numpy

arr = numpy.arange(10)

arr = arr + 500

numpy.save('test.npy', arr)

The recipy module includes a script called recipy that can process the stored data. As a first look, you can use the following command, which will pull up details about the run:

recipy search test.npy

On my Cygwin machine (the power tool for Linux users forced to use a Windows machine), the results look like this:

Run ID: eb4de53f-d90c-4451-8e35-d765cb82d4f9 Created by berna_000 on 2015-09-07T02:18:17 Ran /cygdrive/c/Users/berna_000/Dropbox/writing/lj/ ↪science/recipy/my_script.py using /usr/bin/python Git: commit 1149a58066ee6d2b6baa88ba00fd9effcf434689, in ↪repo /cygdrive/c/Users/berna_000/Dropbox/writing, ↪with origin https://github.com/joeybernard/writing.git Environment: CYGWIN_NT-10.0-2.2.0-0.289-5-3-x86_64-64bit, ↪python 2.7.10 (default, Jun 1 2015, 18:05:38) Inputs: none Outputs: /cygdrive/c/Users/berna_000/Dropbox/writing/lj/ ↪science/recipy/test.npy

Every time you run your program, a new entry is added to the test.npy file. When you run the search command again, you will get a message like the following to let you know:

** Previous runs creating this output have been found. ↪Run with --all to show. **

If using a text interface isn't your cup of tea, there is a GUI available with the following command, which gives you a potentially nicer interface (Figure 1):

recipy gui

This GUI is actually Web-based, so once you are done running this command, you can open it in the browser of your choice.

Recipy stores its configuration and the database files within the directory ~/.recipy. The configuration is stored in the recipyrc file in this folder. The database files also are located here by default. But, you can change that by using the configuration option:

[database] path = /path/to/file.json

This way, you can store these database files in a place where they will be backed up and potentially versioned.

You can change the amount of information being logged with a few different configuration options. In the [general] section, you can use the debug option to include debugging messages or quiet to not print any messages.

By default, all of the metadata around git commands is included within the recorded information. You can ignore some of this metadata selectively with the configuration section [ignored metadata]. If you use the diff option, the output from a git diff command won't be stored. If instead you wanted to ignore everything, you could use the git option to skip everything related to git commands. You can ignore specific modules on either the recorded inputs or the outputs by using the configuration sections [ignored inputs] and [ignored outputs], respectively. For example, if you want to skip recording any outputs from the numpy module, you could use:

[ignored outputs] numpy

If you want to skip everything, you could use the special all option for either section. If these options are stored in the main configuration file mentioned above, it will apply to all of your recipy runs. If you want to use different options for different projects, you can use a file named .recipyrc within the current directory with the specific options for the project.

The way that recipy works is that it ties into the Python system for importing modules. It does this by using wrapping classes around the modules that you want to record. Currently, the supported modules are numpy, scikit-learn, pandas, scikit-image, matplotlib, pillow, GDAL and nibabel.

The wrapper function is extremely simple, however, so it is an easy matter to add wrappers for your favorite scientific module. All you need to do is implement the PatchSimple interface and add lists of the input and output functions that you want logged.

After reading this article, you never should lose track of how you reached your results. You can configure recipy to record the details you find most important and be able to redo any calculation you did in the past. Techniques for reproducible research are going to be more important in the future, so this is definitely one method to add to your toolbox. Seeing as it is only at version 0.1.0, it will be well worth following this project to see how it matures and what new functionality is added to it in the future.

If a problem has no solution, it may not be a problem, but a fact—not to be solved, but to be coped with over time.

—Shimon Peres

Happiness lies not in the mere possession of money. It lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort.

—Franklin D. Roosevelt

Do not be too moral. You may cheat yourself out of much life. Aim above morality. Be not simply good; be good for something.

—Henry David Thoreau

If you have accomplished all that you planned for yourself, you have not planned enough.

—Edward Everett Hale

The bitterest tears shed over graves are for words left unsaid and deeds left undone.

—Harriet Beecher Stowe