Connect to the Internet, work with your files, lock your workspace, listen to music and do so much more with the help of Bluetooth technology.

In an effort to bring more comfort and security to listening to music via headphones while cycling, Swedish telecom vendor Ericsson invented Bluetooth—a wireless connectivity technology, which dates back to 1994. Since then, the standards behind Bluetooth have greatly evolved, but it still remains a niche technology, not widely used outside traditional business applications.

How can you benefit from using Linux on a Bluetooth-equipped PC? There are many use cases, some of which are unconventional and even mind-blowing.

Bluetooth in Linux is powered by the BlueZ software stack. It includes basic tools for remote device discovery and setup. Using it, you can collect some helpful information about the devices and people around you.

To start, let's see what devices are reachable for local discovery:

hcitool scan

You'll get a list of devices with their BD_ADDR values (similar to MAC) and possibly text descriptions. These descriptions are optional, and some users advisedly leave them blank. But still there's a way to find some information on such devices. You can find the class code of a device if you run the hcitool inq command. After that, you can analyze it with the Bclassify utility (github.com/mikeryan/btclassify), which accepts class code as an input parameter and gives back class disentanglement. Here is the example 0x5a020c code:

atolstoy@linux:~/Downloads/btclassify-master> ./btclassify.py ↪0x5a020c 0x5a020c: Phone (Smartphone): Telephony, Object Transfer, ↪Capturing, Networking

Then you can find what services are supported by the device. Here is the sample output:

atolstoy@linux:~> sdptool browse 11:22:33:44:55:66 | ↪grep Service\ Name Service Name: Headset Gateway Service Name: Handsfree Gateway Service Name: Sim Access Server Service Name: AV Remote Control Target Service Name: Advanced Audio Service Name: Android Network Access Point Service Name: Android Network User Service Name: OBEX Phonebook Access Server Service Name: SMS Message Access Service Name: OBEX Object Push

Note that sdptool works even when the device is not discoverable, but is somewhere nearby. Using that technique, you can discover smartphones, headsets, printers, wearable gadgets and, of course, desktops and laptops. On many Mac OS X systems, Bluetooth is set in discoverable mode silently and forever, plus it carries the owner's name in the device's description, which is perfect for amateur social engineering.

Although a Bluetooth connection is not very speedy when it comes to transferring files, it still is a viable option. In Linux, there are several ways to access your device's memory via Bluetooth, and all of them play with the OBEX protocol.

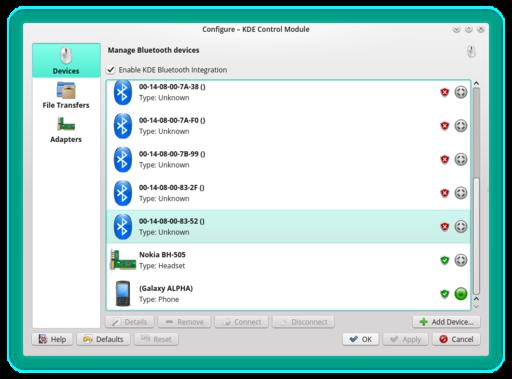

Figure 1. If your neighborhood is densely populated, you'll see an abundance of ready-to-connect Bluetooth devices.

To make use of it, you'll need a phone or a smartphone that supports ObexFTP service. Most legacy devices do, but some modern Android smartphones don't include ObexFS support by default. Luckily, you easily can fix it by installing a third-party Obex server from Google Play (like this: bit.ly/1BjUkEw) and re-connecting your device with the Linux PC. After that, both GNOME Bluetooth and Bluedevil will show you an option for browsing the device, and if you click it, a Nautilus/Nemo/Dolphin window will appear with your device's contents.

However, let's go a little further this time and mount a Bluetooth device as a regular filesystem.

Assuming that you know its BD address and created a directory for mounting, do the following:

obexfs -b 11:22:33:44:55:66 /path/to/directory

To unmount it, use the fusermount command:

fusermount -u /path/to/directory

You even can do an auto-mounting of your Bluetooth filesystem in the traditional UNIX-style way. Just add the following line to your /etc/fstab:

obexfs#-b11-22-33-44-55-66 /path/to/directory ↪fuse allow_other 0 0

By default, only the current user will see the mounted filesystem. That's why the allow_other option is needed. Keep in mind that it might be a security risk to allow everybody to see remote filesystems.

The obexftp command is used for sending and receiving files without mounting a filesystem. You can send any file to your device by issuing a command like this:

obexftp -b 11:22:33:44:55:66 -p /some/file/to.put

The file will land in the default “Received files” directory on your device. To retrieve a file from the phone, just change the command a little:

obexftp -b 11:22:33:44:55:66 -g to.get

The Bluetooth receiver in Linux is managed via the BlueZ software stack, which, in turn, can scan your surroundings for other Bluetooth devices. A common case is a desktop or laptop PC, which you can pair with your smartphone. On the PC side, the Bluetooth adapter not only scans the range (it's the hcitool scan command), but it also estimates the strength of the signal. The stronger the signal, the closer the device is. You can make use of it if you associate a change in proximity with some action. For example, you can lock your PC when you're away and unlock it when you approach it again. From a third-party's view, this will look like magic.

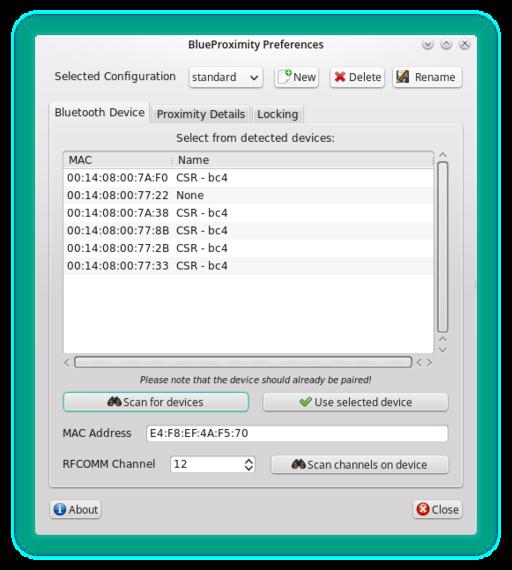

Figure 2. After spending a couple minutes to fine-tune proximity settings, you can surprise your friends with a PC that responds to your approach.

Linux has a ready-to-use solution for this purpose, and it's called Blueproximity. The utility is a Python wrapper over the rfcomm and hcitool commands, with a nice GTK2 user interface. Blueproximity is widely available across most Linux distributions, so just install it using your standard package manager.

After you launch the application, a tray icon will appear on your panel. Click it to open the Blueproximity settings window. Make sure you've enabled the Bluetooth discovery on your phone, and then press the “Scan for devices” button. Select your phone (a caption will help you recognize it) and then go to the Proximity details tab. Here you can adjust the locking and unlocking distance and duration. Drag the sliders to make the values work best. The values depend on your room configuration, Bluetooth adapter active range and numerous other details. But to make things work, go to the Locking tab and make sure the commands there work for you. The Blueproximity defaults are designed to work in GNOME, Mate, XFCE, Cinnamon and Unity environments, so if you happen to use one of those, no changes are needed. In the case of KDE, use the following replacements:

qdbus org.kde.screensaver /ScreenSaver Lock

↪// for locking the screen

qdbus | grep kscreenlocker_greet | xargs -I {} qdbus

↪{} /MainApplication quit // for unlocking

qdbus org.freedesktop.ScreenSaver /ScreenSaver

↪SimulateUserActivity // for simulating user activity.

After you close the Settings window, you're ready for a test run. Walk back and forth to make sure that the values in Blueproximity are comfortable, and try the auto-locking and unlocking trick. If for some reason you need to monitor the proximity without bringing the Blueproximity setting window to the front, use the following command:

watch -n 0.5 hcitool rssi 11:22:33:44:55:66

where 0.5 is the refresh period and 11:22:33:44:55:66 is your phone's BD ADDR address. To find your address, simply run hcitool scan on the command line.

It's always good to have a backup Internet connection. Sometimes your main provider fails, or there is some service downtime, or whatever. Having another connection via your mobile carrier is great, but you may want to share this connection on your desktop PC. Basically, there are two methods for accomplishing it: launching a Wi-Fi ad hoc spot on a phone and connecting with Bluetooth. Let's look at the latter case.

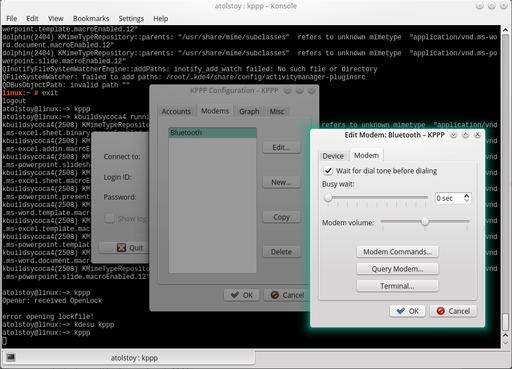

Figure 3. Although it looks like a retro type of connectivity, PPP perfectly supports all the latest tech novelties, including broadband LTE.

Pairing your phone with a PC via Bluetooth is commonly done for browsing files, while binding makes the phone accessible as a /dev/rfcommX device (usually rfcomm0). This is a network device, and it can be used in the same way as a dial-up modem. After that, you can set a PPP (point-to-point) connection either with NetworkManager, KPPP, wvdial or the standard network-managing commands of your system (like the legacy ifup/ifdown commands). Here, I cover the KPPP method. Once you install the KPPP package, you're ready to go.

First, make sure your phone can access the Internet—this can narrow your search for a bottleneck if something goes wrong. Mobile phones are capable of doing this since the early 2000s, although 3G and LTE speeds came later. Then enable Bluetooth on the phone and make it discoverable (for security reasons, it is disabled by default on most devices).

On the desktop side, you'll need to pair your phone with a PC. In the past, this was done manually by changing the BlueZ config files, but on modern desktops, all you have to do is use either the GNOME Bluetooth applet or Bluedevil to create a simple pairing.

Check whether your device has emerged on the PC side by issuing the sudo ls /dev/rfcomm* command. If it's not there, you'll need to do things manually:

hcitool scan // find your phone's address sdptool search DUN // find the channel for dial-up networking (DUN) rfcomm bind 11:22:33:44:55:66 1 (where 1 is a channel number) sudo chmod 777 /dev/rfcomm0 // that will let us run KPPP ↪without root privileges

After that, it's time to run KPPP and set the connection details. Click Configure→Modems→New, and select /dev/rfcomm0 as your device. Press the “Query Modem...” button, and make sure that the modem device responds.

To establish a connection, you will need to alter the “Initialization string 1”, which is in the “Modem Commands” window. The string differs between carriers, so you'll need to get the proper one. For example, Verizon in the US accepts the following:

AT+CGDCONT=3,"IPV4V6","vzwinternet","0.0.0.0",0,0

When your modem is set up, create a standard connection in KPPP. The only thing you need to know is the dial-in number, which can look like *99***3# (for example, for Verizon). The user name and password fields can be left blank or filled with random characters, as they're not required. Finally, press the Connect button in the main KPPP window and wait for a successful link.

A useful and impressive trick is streaming your audio playback from your Bluetooth-enabled phone to your desktop PC (perhaps with powerful speakers attached). Or, it can be applied to your car system, so you can listen to your favorite tunes while driving.

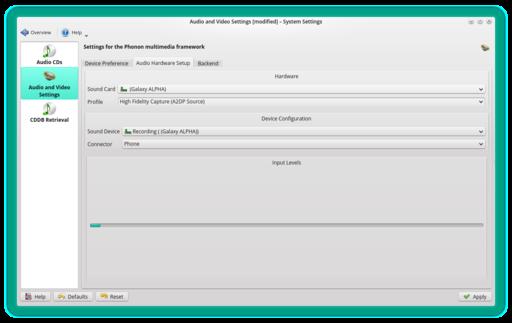

Figure 4. Previous versions of BlueZ in Linux required extra skill to stream audio to remote output. Now all the setup steps are just a few clicks away.

The setup procedure is straightforward, because your phone services are discovered automatically when it is paired with a PC. After that, open your Pulseaudio control window (Pavucontrol or Audio and Video Settings in KDE's system settings) and find your phone as an Input device. In the case of Android phones, enable multimedia streaming in the Bluetooth settings, and you're done.

Thanks to Pulseaudio, you can use your Bluetooth headset in a similar way—set it as a priority recording and playback device. To do this, you'll have to switch the profile from A2DP (high-quality stereo) to HSF/HFP (headset mode). It plays and records only in mono, but you can get an extra benefit from Pulseaudio by utilizing it as a built-in noise and echo filter. For example, let's launch Skype with that filter:

PULSE_PROP="filter.want=echo-cancel" skype

You can switch between Pulseaudio output (sinks) and input (sources) devices using the pactl and pacmd commands, which work the same way on any Linux system.

The opposite way is limited though. You can stream audio from your Linux PC to a headset or Bluetooth speakers, but in the case of Android phones, it's possible only via Wi-Fi, not Bluetooth.

This mostly applies to older phones, like the Nokia S40 and S60 phones, Sony Ericsson and so on. These phones still are widely used as backup phones, because they're rugged, friendly and easy to use. Unlike modern smartphones running Android or iOS, these mobile phones don't have advanced sync options with on-line services. Instead, you can retrieve various data stored on such a phone via Bluetooth. This is particularly useful if you own an old mobile phone, and there's no way to get into its memory other than wirelessly.

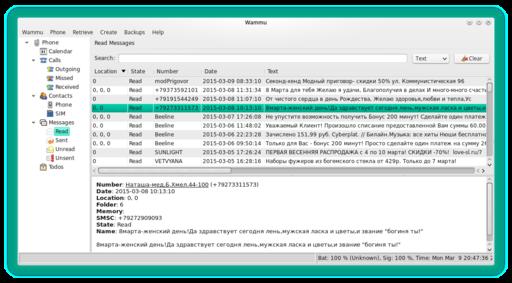

Figure 5. A phone itself might not be worth a penny, but if it stores precious content, it can be carefully retrieved and saved by Wammu.

On Linux, there's a mature and feature-rich application for that purpose: Wammu. Go ahead and install it from your favorite Linux distribution (it's available almost everywhere). Once it is installed, launch it and follow the first-time connection wizard. When prompted about connection type, choose Bluetooth, enable it on the phone and click Next. The wizard may ask you a few more details about the connection, but you should be finished in a minute or two. Thousands of phones are supported, so your model most likely will be on the whitelist.

In the main Wammu window, choose Phone→Connect, and make sure the connection is established. Now you can retrieve data from the phone, including Contacts (either on SIM or in phone memory, or both), Calls History, Messages, To-Dos and Calendar. All of those options are available from the Retrieve menu. Whatever you choose, no changes will be made on the phone side, so it's absolutely safe.

The left part of the Wammu window hosts a category tree, where you can switch from one data section to another. You can add, edit or remove items and contents, which is far more comfortable than struggling with phone controls and reading a tiny screen. One of Wammu's best features is the ability to back up and restore retrieved data. Look under the Backups menu for importing/exporting and saving options. If you wish to transfer data from one phone to another, there's no better choice than Wammu.