Until now we've been consenting to what Web sites and apps want, but soon it'll also be the other way around.

Whatever your opinions about Do Not Track, set them aside for a minute and just look at what the words say and who says them. Individuals—the people we call “users” (you know, like with drugs)—are the ones saying it. In grammatical terms, “do not track” is spoken in the first person. In legal terms, it's spoken by the first party. The site is the second person and the second party. The unwanted tracking is mostly by a third person them: third parties the first one doesn't want following him or her around. In both the grammatical and the legal senses, individuals want consent to the Do Not Track request. And mostly they don't get it.

It's easy to lay the blame on lack of agreement about what Do Not Track does, or should do, and how. But the real problem is deeper: in the power asymmetry of client-server, which we might also call calf-cow (Figure 1).

In client-server, we're calves and sites are cows. We go to sites to suckle “content” and get lots of little unwanted files, most of which are meant to train advertising crosshairs on us. Having Do Not Track in the world has done nothing to change the power asymmetry of client-server. But it's not the only tool, nor is it finished. In fact, the client-side revolution in this space has barely started.

I am writing this to prepare for a talk I'll give (as a Linux Journal editor) at the Workshop on Meaningful Consent in the Digital Economy 2015. It's at the University of Southampton in the UK on February 26, which means it will have happened by the time you read this. It will be interesting to see how coverage differs from what I'm planning to say, and you're about to read.

By “meaningful consent”, they mean “issues related to giving and obtaining user consent online, with special emphasis on privacy and data protection”. I'm focusing on the giving side, because that's the frontier. Very few commercial sites give consent to users of any meaningful kind—except, perhaps, as legal butt-covering. (“Here's our consent: go look at our privacy policy.”) And there are few ways for individuals to express the desire for consent, especially around privacy. (Do Not Track is just one of them.) Basically we travel the Web naked, unless we're wizards (such as Linux Journal readers) who know how to secure their on-line homes, wear the right protective clothing and customize their own vehicles. But ways are being developed for the muggles of the world, and I want to run a few of those down. Here they are:

Do Not Track.

Ad and tracking blockers.

Privacy icons.

UMA (User Managed Access).

IDESG's Internet Ecosystem Steering Group.

Open Notice and Consent Receipts.

Respect Trust Framework.

Customer Commons' user-submitted terms.

CommonAccord's Digital Law Commons.

1. Do Not Track is an HTTP header (DNT) that asks a site or an app to disable unwanted tracking. There is disagreement about what kinds of tracking should be disabled and how various things work. But all the browser makers enable it (in different ways), so that's progress. And, regardless of whatever becomes of DNT, the step is still in the right direction, because it carries a signal of intent from the individual. Consent comes back the other way—or should. (I first heard of DNT from Chris Soghoian at a Berkman Center meeting in the late 2000s. Chris, Sid Stamm and Dan Kaminsky are regarded as DNT's original authors. In recent years, the W3C has carried the DNT ball, through many internal and external disagreements—especially with the IAB and the DAA. (Chris also published a detailed history of DNT in January 2011.)

2. Ad and tracking blockers selectively throttle tracking, advertising or both. Here's a partial list of the ones I have installed on my own browsers:

Adblock Plus: https://adblockplus.org.

AVG PrivacyFix: www.avg.com/us-en/privacyfix.

Customer Commons Web Pal: customercommons.org/about-web-pal.

Disconnect: https://disconnect.me.

Ghostery: https://www.ghostery.com/en.

Privacy Badger: https://www.eff.org/privacybadger.

PrivownyBar: https://privowny.com.

Each has advantages, none of which I'll visit here. As for consent, they all fail to signal much if anything. Their main work is prophylactic.

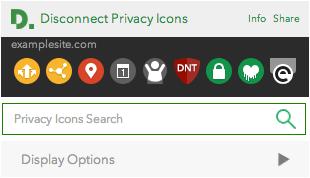

3. Privacy icons are visual signals. Disconnect's can “read and change all your data on the websites you visit”. They look like Figure 2.

Figure 2. Privacy Icons

An earlier effort is Aza Raskin's, which became Mozilla's. The following is a list of what each symbol says. (The images are gone from Aza's original post, but are available at his Flickr site with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license. Since Linux Journal is commercial, we'll leave seeing them up to you—see Resources.)

Your data is only for the intended use.

Your data may be used for purposes you do not intend.

Your data is never bartered or sold.

Your data may be bartered or sold.

Your data is never given to advertisers.

Site gives your data to advertisers.

Your data is given to law enforcement only when legal process is followed.

Data may be given to law enforcement even when legal process is not followed.

Your data may be kept for less than one month (or three, or six, or eighteen months).

Your data may be kept indefinitely.

Those would be handy. Alas, the commercial Web site publishing business has shown little interest in them and will continue so as long as all the signaling is left up to them.

4. UMA—User Managed Access is the brainchild of Eve Maler (currently an analyst with Forrester Research), and its home is the User Managed Access WG (Working Group) at Kantara. UMA's charter is “to develop specs that let an individual control the authorization of data sharing and service access made between online services on the individual's behalf, and to facilitate interoperable implementations of the specs”. It's an OAuth-based protocol. Token movement through UMA currently looks like Figure 3.

5. IDESG's Identity Ecosystem Steering Group is part of NSTIC: the National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace, which was launched by the White House in 2011 and is meant to create an implementation road map that will reside within the Department of Commerce. The IDESG is working toward “secure, user-friendly ways to give individuals and organizations confidence in their online interactions”. Here's the wiki: https://www.idecosystem.org/wiki/Main_Page. And here is the User Experience Committee: https://www.idecosystem.org/group/user-experience-committee, which is taking the lead on this thing.

6. Open Notice and Consent Receipts is an OpenNotice.org project, “a group of people and projects that are innovating to address the broken notice and consent infrastructure to enable greater control of personal data”. Its main focus is on the consent receipt project. Work here lives at the Consent & Information Sharing Work Group (CISWG) at Kantara. The purpose is to specify receipts of consent exchanged between first and second parties. Everything else I can tell you about it is beyond complicated. What matters is that it's being worked on by highly committed people who not only grok it, but also are working to simplify it.

7. Respect Trust Framework is one of five frameworks created by the Open Identity Exchange. This one requires that parties to the framework promise to “respect each others' digital boundaries”. This past year many individuals, companies and development projects (me included) joined with the Respect Network (“the first global ecosystem for trusted personal information exchange”) to at least agree to the Framework. Respect Network as a company ran out of runway, but it did succeed in getting the Framework agreed to by a pile of parties, which is an accomplishment by itself.

8. Customer Commons user-submitted terms is intended to do for individual terms what Creative Commons did for copyright licenses. Figure 4 shows one straw man proposal, drawn originally on a whiteboard at VRM Day in October 2014.

It derives from EmanciTerms, by ProjectVRM, and which I described like this in The Intention Economy:

With full agency...an individual can say, in the first-person voice, “I own my data, I control who gets access to it, and I specify what I wish to happen under what conditions.” In the latter category, those wishes might include:

Don't track my activities outside of this site.

Don't put cookies in my browser for anything other than helping us remember each other and where we were.

Make data collected about me available in a standard, open format.

Please meet my fourth-party agent, Personal.com (or whomever).

These are EmanciTerms, and there will be corresponding ones on the vendor's side. Once they are made simple and straightforward enough, they should become normative to the point where they serve as de facto standards, in practice.

Since the terms should be agreeable and can be expressed in text that code can parse, the process of arriving at agreements can be automated.

The mission of Customer Commons (a nonprofit spin-off of ProjectVRM), is “to restore the balance of power, respect and trust between individuals and the organizations that serve them”. Toward making that happen through EmanciTerms, Customer Commons has engaged the Cyberlaw Clinic at the Berkman Center and Harvard Law School, which “provides high-quality, pro-bono legal services to appropriate clients on issues relating to the Internet, new technology, and intellectual property”. It's still early in that process, but the end result will be terms that you and I can assert, and others will need to accept.

9. CommonAccord's Digital Law Commons is an end state when you have what Jim Hazard and Primavera De Filippi call “a way of rendering a document from snippets of text organized as key-values in lists—a 'graph'. It's applicable to a lot of knowledge management tasks, but especially useful for codifying legal docs”. In slightly more technical terms, the Common Accord site explains, “We have created a modular template system of text cards that relies on {expansion} of strings and [expansion] of cards. Period. People can program their relationships. Lawyers can codify boilerplate. Management can have a data picture of the enterprise's relationships, situation and activities. Smart contracts can be both technical 'dry' code (i.e. self-contained code snippets) and legal 'wet' code. With Common Accord, contract and legal text becomes cards of text, interoperating, in git, shared, forked, tested and improved.” Here it is on Github: https://github.com/CommonAccord/Org/tree/master/Doc.

I expect many of these efforts to merge, support each other and cross-fertilize. There is a lot of convergence already.

Why should I be optimistic about results? Four reasons.

First is tech. Code is law, Professor Lessig taught us, and the code required for asserting and agreeing to terms won't be terribly complicated.

Second is publicity. We—Customer Commons (on the board of which I sit) and friends—will make a Big Thing out of the term, once we have them, just like Creative Commons made a Big Thing out of its licenses when those came out. Sites and services that don't listen to what users and customers want will be exposed and shamed. Simple as that.

Third is pickup. It won't be hard for organizations like Consumer Reports—as well as everybody in the lazyweb's long tail—to give thumbs-up and thumbs-down to sites and services that agree to simple and reasonable terms submitted by customers and users.

Fourth is performance. As I put it in The Intention Economy:

Rather than guessing what might get the attention of consumers—or what might “drive” them like cattle—vendors will respond to actual intentions of customers. Once customers' expressions of intent become abundant and clear, the range of economic interplay between supply and demand will widen, and its sum will increase. The result we will call the Intention Economy.

This new economy will outperform the Attention Economy that has shaped marketing and sales since the dawn of advertising. Customer intentions, well expressed and understood, will improve marketing and sales, because both will work with better information, and both will be spared the cost and effort wasted on guesses about what customers might want, flooding media with messages that miss their marks. Advertising will also improve.

The volume, variety, and relevance of information coming from customers in the Intention Economy will strip the gears of systems built for controlling customer behavior or for limiting customer input. The quality of that information will also obsolete or repurpose the guesswork mills of marketing, fed by crumb trails of data shed by customers' mobile gear and Web browsers. “Mining” of customer data will still be useful to vendors, though less so than intention-based data provided directly by customers.

In economic terms, there will be high opportunity costs for vendors that ignore useful signaling coming from customers. There will also be high opportunity gains for companies that take advantage of growing customer independence and empowerment.

But first we need the code. I expect we'll see enough to get started before this year is out.