Once in a while someone points out a POSIX violation in Linux. Often the answer is to fix the violation, but sometimes Linus Torvalds decides that the POSIX behavior is broken, in which case they keep the Linux behavior, but they might build an additional POSIX compatibility layer, even if that layer is slower and less efficient.

This time, Michael Kerrisk reported a POSIX violation that affected file operations. Apparently, reading and writing to files during multithreaded operations could hit race conditions and overwrite each other's changes.

There was some discussion over whether this was really a violation of POSIX, but ultimately, who cares? Data clobbering is bad. After Michael posted some code to reproduce the problem, the conversation focused on what to do to fix it. But Michael did make an argument that “Linux isn't consistent with UNIX since early times. (E.g., page 191 of the 1992 edition of Stevens APUE discusses the sharing of the file offset between the parent and child after fork(). Although Stevens didn't explicitly spell out the atomicity guarantee, the discussion there would be a bit nonsensical without the presumption of that guarantee.)”

Al Viro joined Linus in trying to come up with a fix. Linus tried introducing a simple mutex to lock files so that write operations couldn't clobber each other, and Al offered his own refinements that improved on Linus' patch.

At one point, Linus explained the history of the bug itself. Apparently, once upon a time the file pointer, which told the system where to write into the file, had been locked in a semaphore so only one process could do anything to it at a time. But, they took it out of the semaphore in order to accommodate device files and other non-regular files that ran into race conditions when users were barred from writing to them whenever they pleased.

That was what introduced the bug. At the time, it slipped through undetected, because that actual reading and writing to regular files was still handled atomically by the kernel. It was only the file pointer itself that could get out of sync. And, because high-speed threaded file operations are a pretty rare need, it took a long time for anyone to run into the problem and report it.

An interesting little detail is that, while Linus and Al were hunting for a fix, Al at one point complained that the approach Linus was taking wouldn't support certain architectures, including ARM and PowerPC. Linus' response was, “I doubt it's worth caring about. [...] If the ARM/PPC people end up caring, they could add the struct-return support to gcc.”

It's always interesting to see how corner cases crop up and get dealt with. In some cases, part of the fix has to happen in the kernel, part in GCC and part elsewhere. In this particular instance, Al felt the whole thing could be done in the kernel, and he was inspired to write his own version of the patch, which Linus accepted.

Andi Kleen wanted to add low-level CPU event support to perf. The problem was that there could be tons of low-level events, and it varied widely from CPU to CPU. Even storing the possible events in memory for all CPUs would significantly increase the kernel's running size. So, hard-coding this information into the kernel would be problematic.

He pointed out that the OProfile tool relied on publicly available lists of these events, though he said the OProfile developers didn't always keep their lists up to date with the latest available versions.

To solve these issues, Andi submitted a patch that allowed perf to identify which event-list was needed for the particular CPU on the given system, and automatically download the latest version of that list from its home location. Then perf could interpret the list and analyze the events, without overburdening the kernel.

There was various feedback to Andi's code, mostly to do with which directory should house the event-lists, and what the filenames should be called. The behavior of the code itself seemed to get a good reception. One detail that may turn out to be more controversial than the others was Andi's decision to download the lists to a subdirectory of the user's own home directory. Andi said that otherwise users might be encouraged to download the event-lists as the root user, which would be bad security practice.

Sasha Levin recently posted a script to translate the hexadecimal offsets from stack dumps into meaningful line numbers that pointed into the kernel's source files. So something like “ffffffff811f0ec8” might be translated into “fs/proc/generic.c:445”.

However, it turned out that Linus Torvalds was planning to remove the hex offsets from the stack dumps for exactly the reason that they were unreadable. So Sasha's code was about to go out of date.

They went back and forth a bit on it. At first Sasha decided to rely on data stored in the System.map file to compensate, but Linus pointed out that some people, including him, didn't keep their System.map file around. Linus recommended using /usr/bin/nm to extract the symbols from the compiled kernel files.

So, it seems as though Sasha's script may actually provide meaningful file and line numbers for debugging stack dumps, assuming the stack dumps provide enough information to do the calculations.

Apps like Instagram have made photo filters commonplace. I actually don't mind the vintage look for quick cell-phone snapshots, but a filter can do only so much. At first glance, Repix is another one of those “make your photo cool” apps that does little more than add a border and change saturation levels. It is more than that, however, taking photo modification to the next level and making it art.

The photo here, for instance, is from the Repix Flickr stream. It's obviously been filtered, but you're sure to notice there's a lot more going on. I'm not a terribly visually artistic person, but Repix allows a few simple touches to make a beautiful difference. If you're looking for a simple way to make your cat photos a little more exciting, but don't want to have to transfer photos to a desktop application, check out Repix. The standard features are free, but with an in-app purchase, you can get more packages to play with.

Due to its ability to help a luddite like myself create artsy photographs, Repix gets this month's Editors' Choice award. If you like to take photos, but don't have an artistic bone in your body, I urge you to check it out. It's in the Play Store, but the Web site is www.repix.it.

I've always loved PHPMyAdmin for managing MySQL databases. It's Web-based, fairly robust and as powerful as I've ever needed. Basically, it's awesome. Today, however, I discovered something better than awesome: Adminer. Although it is conceptually identical to PHPMyAdmin, it is far simpler and far more powerful. How can it be both? The Adminer Web site has a great feature comparison: www.adminer.org/en/phpmyadmin.

For me, the interface is basic, no-nonsense and intuitive. I like that installation is a single PHP file, and I also like that it supports alternate database systems like Postgres. If you are someone who prefers to use a Web interface over the command line, don't be ashamed. Heck, I recently managed an entire database department at a university, and I still prefer a Web-based interface. Anyway, if you're like me, you'll love Adminer. Get your copy today at www.adminer.org.

We're moving Letters to the Editor to www.linuxjournal.com/letters to provide faster feedback and allow readers to comment. Please continue to send comments and feedback as usual via www.linuxjournal.com/contact or e-mail info@linuxjournal.com. We look forward to hearing from you!

As I write this, NASA has just passed another milestone in releasing its work to the Open Source community. A press release came out announcing the release on April 10, 2014, of a new catalog of NASA software that is available as open source. This new catalog includes both older software that was previously available, along with new software being released for the first time. The kinds of items available include project management systems, design tools, data handling and image processing. In this article, I take a quick look at some of the cool code available.

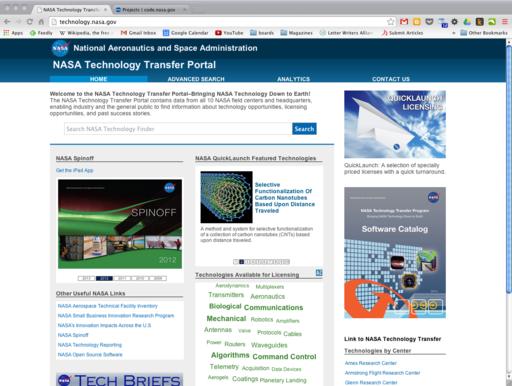

The main Web site is at technology.nasa.gov. This main page is a central portal for accessing all of the technology available to be transferred to the public. This includes patents, as well as software.

Figure 1. The main technology transfer site is a portal to provide access to everything NASA has to offer.

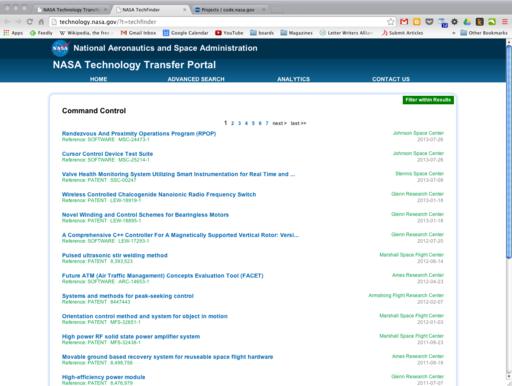

As a quick start, there is a subject cloud in the lower central region of the page that can do a search on several different keywords for you. Unfortunately, this is only a catalog of all the offerings, and it's not quite complete yet in terms of detailed information. So, for example, if you click on Command Control, you will be taken to a results page that includes items like Rendezvous and Proximity Operations Program (RPOP). If you click on that, you will be taken to a details page that is essentially unpopulated. The assumption is that this will be filled in as time allows in the future. It does give you a list of what is available though, which is half the battle.

Figure 2. The results page on a search will give you a list of software and patents that are available from NASA.

Staying on the result list page, you should notice that there is the name of a NASA center on the right-hand side of each line. This is the actual source for the given patent or software entry. Once you find something of interest, you can go to the individual center's Web site to find more details about it. On the lower-right section of the main page of the NASA technology site, you can find direct links to the technology sections for each of the individual centers. The amount of information available at each of these centers varies, but you should be able to find out more details. Some of the sites have direct download links, so you can get the software that interests you. In other cases, sites provide only the contact details for a person you'll need to talk to in order to get copies of the software in question. A PDF catalog also is available on the front page of the main technology site. Here, you can get a 172-page catalog of all of the available software, broken down into 15 categories, for off-line access.

One issue that will become evident right away is that not everyone can access all of the available software. Some of the released software is available only to US residents, and some is even more restricted to only parts of the US government. So, is there an easier option for the international community? On the front page, there is a set of other useful NASA links on the lower-left side. The one labeled NASA Open Source Software (code.nasa.gov) will take you to a sister site that provides access to a more centralized repository of software released as open source. It is laid out as a list of available code within a WordPress blog, and it looks like it's being updated regularly. So, it's worth keeping an eye on this site for future releases.

So far, I haven't yet looked at what kind of software is available from the technology exchange at NASA, and there is a rather broad collection to play with. The first one I look at here is the Mission Control Technologies (MCT). This package, hosted on GitHub, provides a real-time monitoring and visualizing platform that was developed at the Ames Research Center for use in spaceflight mission operations. It is based on configurable components, so you can use this to build your own application to monitor pretty much anything.

If you want to build your own spacecraft to monitor, you will need some way of controlling its flight. Enter the Core Flight Executive (cFE), a portable, platform-independent embedded system framework developed at the Goddard Space Flight Center. It is used for flight software for satellite data systems and instruments, but you can use it for other embedded systems. It is built from subsystems including executive services, time services, event services, table services and a software bus. Python programmers can download SunPy, a library to handle several tasks you run into when doing solar science.

For many scientific applications, you need to use clusters of machines. NASA is no exception to this. To handle the complexities, several software packages are available. For dealing with files, there are the Multi-Thread Multi-Node Utilities (Mutil). Mutil provides mcp and msum, which allow for parallelized access to files for moving around a cluster. If you have a cluster of machines available over SSH, you can use them with Mesh (Middleware Using Existing SSH Hosts). Mesh provides a lightweight grid middleware that can group your cluster hosts into execution units. You then can issue a command, and Mesh will handle going to one of the available hosts in your group and running this command. If you need an interactive session, there is Ballast (Balancing Load Access Systems). With Ballast, when you try to SSH in to your cluster, you actually end up being shunted onto an available host within your cluster automatically.

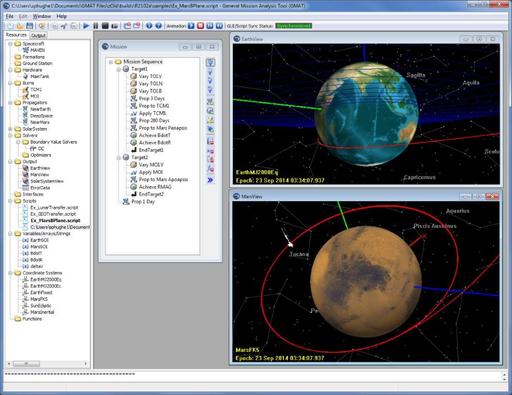

The last package I want to look at is mission analysis. There is the General Mission Analysis Tool (GMAT), which is designed to help you plan your next trip to Mars. You can use GMAT to model, optimize and estimate spacecraft trajectories. You can create physical resources required for the trip, like the spacecraft, thruster, tank, ground station and so on, and model how the trip will play itself out. There also are analysis model resources, including differential correctors, propagators and optimizers to define the details of the model. The user guide describes the multitude of available options. There also is a series of tutorials, including simulating an orbit, doing simple orbit transfers or even planning an optimal lunar flyby using multiple shooting that walks you through how to use GMAT in greater detail.

Figure 6. GMAT can help you plan out your next deep space mission from the comfort of your own living room.

Now that you've looked at some of the newly released code from NASA, hopefully your interest is piqued enough to go exploring through the more than 1,000 other pieces of code available there. You never know what you may find. If you find something really interesting, please share it with the rest of us!

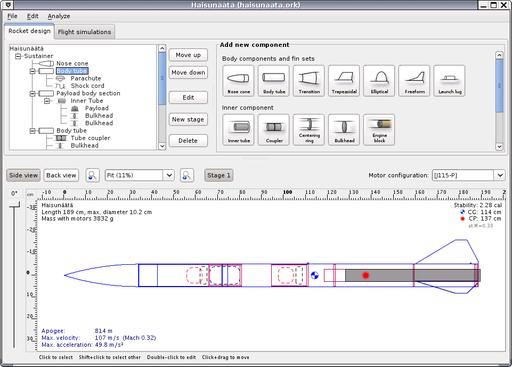

I've never once made a model rocket. I've always wanted to, but apart from “tube with explodey rocket part”, I really didn't know where to start with designing. I recently found an open-source application that should help me with my lack of rocket science know-how: OpenRocket.

The aspect of actually designing a rocket appeals to me, because not only will I have a better chance of launching a rocket successfully, but I'll also be able to compare expected results with actual results. If my carefully designed rocket veers into the neighbor's yard and blows up the dog house, I want to be able to figure out why!

Screenshot from the OpenRocket Web Site (openrocket.sourceforge.net) Depicting a 2-D View of the Rocket Design Process

If you've always wanted to launch a model rocket, but never had that really cool middle-school science teacher that showed everyone how, check out OpenRocket. Even if you did launch rockets in school, with OpenRocket, you should be able to design a far more complex (and more awesome!) design on your computer. If you have any success with your pre-designed rocket, I'd love to see a video! Send a YouTube link to info@linuxjournal.com.

Take the attitude of a student, never be too big to ask questions, never know too much to learn something new.

—Og Mandino

It is curious that physical courage should be so common in the world and moral courage so rare.

—Mark Twain

Observe your enemies, for they first find out your faults.

—Antisthenes

We act as though comfort and luxury were the chief requirements of life, when all that we need to make us happy is something to be enthusiastic about.

—Charles Kingsley

You don't become great by trying to be great. You become great by wanting to do something, and then doing it so hard that you become great in the process.

—Randall Munroe

No matter how much I love Plex, there's still nothing that comes close to XBMC for usability when it comes to watching your network media on a television. I've probably written a dozen articles on Plex during the last few years, so you know that's tough for me to admit. Still, no matter how many Plex-enabled devices I might buy (Roku, Amazon Fire TV, phones, tablets, Web browsers), I run XBMC on all my televisions. The interface, when coupled with a back-end MySQL database, is just unbeatable.

My ultimate dream is that XBMC and Plex would somehow merge together into an incredible living room experience that also kicks butt on a mobile device. Until that day of convergence, I'll keep supporting two platforms. And, the XBMC platform recently got a significant upgrade. Version 13, code-named “Gotham” was released in May 2014. By the time you read this, 13.1 should be out, which fixes some bugs.

I'm most happy to see continued improvements with the Live TV and PVR features. Add to that further optimization for Android and Raspberry Pi devices, and XBMC is by no means out of the game. I'm excited to see XBMC continue along at a steady development pace. So, my weekend project once Saturday rolls around? Upgrading all my televisions to Gotham. Get a copy today at www.xbmc.org.