BirdCam is back—now with HD video and archives.

In the October 2013 issue, I described the hardware and software I used to create my “BirdTopia Monitoring Station”, more commonly called BirdCam. If you've been visiting BirdCam recently, which a surprising number of folks have been doing, you'll notice quite a few changes (Figure 1). In this article, I describe the upgrades, the changes and some of the challenges along the way. If you like fun projects like these involving Linux, please read on and join in my birdy obsession!

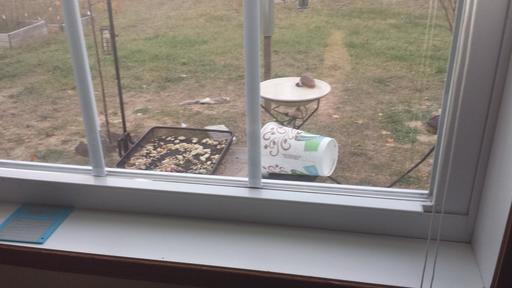

One of the first changes I wanted to make to BirdCam was to zoom in a bit on the feeders. Yes, the enormous photo provided by the Galaxy S2 phone mounted in the window is nice, but for displaying on a computer screen (or HDTV, as I'll talk about later), a 1920x1080-size snapshot is really ideal. Unfortunately, when I crop the photo, it leaves out the birdbath. Because I spent the money on a heated birdbath this winter, I didn't want to miss out on any candid water shots. You can see in Figure 2 how I planned to zoom in on the bird feeders and then relocate the birdbath onto what was left of the photo. Although it took a bit of trial and error, the code for doing this was remarkably easy. I used the convert program from the ImageMagick suite. It might be possible to include the crop and relocate into a single command, but I just created a temp file and then overlayed that temp file later on:

convert /dev/shm/original.jpg -crop 640x360+1800+1425 \

/dev/shm/birdbath.jpg

convert /dev/shm/original.jpg -crop 1920x1080+220+130 \

/dev/shm/birdbath.jpg -gravity southeast -composite \

/dev/shm/final.jpg

Figure 2. My old cell phone takes really high-resolution photos. I was able to clip out the birdbath and overlay it nicely to get a closeup of the feeders.

In the code snippet above, I crop out the small birdbath photo from the original camera photo and save it as birdbath.jpg. Then, with another convert command, I crop the original photo to that 1080p size I mentioned earlier and overlay the birdbath onto the photo with the -composite flag. In this little example, I use the -gravity flag to put the birdbath in the corner. You can be more precise with the -geometry flag, which you'll see in my final script (see Resources).

The original BirdCam article showed how to add a timestamp to the top of the photo, but I didn't mention how I got the temperature. I've since added sunrise and sunset information to the annotation, and made it a little more readable. (Figure 1 shows the annotation in the upper-left corner.)

Although the method for overlaying the information isn't much different (you can check it out in the final script—see Resources for the link), getting the temperature and sunrise/sunset information was challenging. To get the current temperature, I use a little command-line program called weather-util, available in most distro repositories. The program actually gives much more information than is required, so to extract just the temperature, you need to do a little grep-fu:

weather-util -i KPLN | grep Temperature | awk '{print $2}'

This requires a bit of explanation. You need to figure out what your four-letter weather ID is. The best place to find that is at weather.noaa.gov. Find the closest location to you, and then look in the URL at the top for the four-letter code (usually an airport). For example, the Pellston Regional Airport is my closest, so my ID is KPLN. If you're thinking it would be better to get the actual temperature from my backyard, I agree. In fact, I'll be working on setting up my own weather station in the months to come for that very reason.

The rest of the code does two things. Grepping for “Temperature” returns the line of the weather-util results containing the temperature, and then the awk command extracts just the Fahrenheit temperature from that line. I set up a cron job to save the temperature into a text file every few minutes, and I use that file to annotate the BirdCam photo. The sunrise/sunset information is similar, but for that, I use the Yahoo weather information. You'll need your WOEID information, which again is available in the URL when you go to weather.yahoo.com and enter your location information. For example, my weather URL is weather.yahoo.com/united-states/michigan/indian-river-2426936, so my WOEID is 2426936. The rest is fairly easy using more grep-fu. Here's the code for sunrise:

echo `l=2426936;curl -s http://weather.yahooapis.com/

↪forecastrss?w=$l|grep astronomy| awk -F\" '{print $2}'`

And the code for sunset:

echo `l=2426936;curl -s http://weather.yahooapis.com/

↪forecastrss?w=$l|grep astronomy| awk -F\" '{print $4}'`

Much like the temperature, I have a cron job that stores these values into a text file that gets used during the annotation of the final BirdCam graphic. Once I get a local weather station from which I can pull information, I might add wind speed and such. For now, I think it's a useful bit of information.

If you've been following my blog or my Twitter feed, you may have seen a few different iterations of WindowCam. I tried weatherproofing a USB Webcam (Figure 3), which worked until the wind packed snow into the “hood” I created with a Dixie cup. For a long time, I leaned an old iPhone against the window and just extracted a photo to embed into the final BirdCam photo. The iPhone's resolution was only 640x480, so it was fairly simple to embed that image (downloaded directly from the iPhone) using convert.

Figure 3. My Dixie-cup weatherproofing did an okay job, until the snow flew. Now it's inside looking through the window.

But of course, I wanted more. My current window camera is a Logitech C-920 USB Webcam connected to a computer running Linux. At first I connected it to a Raspberry Pi, but the RPi couldn't do more than five frames per second. I wanted 15 frames per second, full HD, so I'm using a full-blown computer. See, not only do I want to embed the window camera into BirdCam, but I also want to have an archive video of the birds that visit my feeder every day.

Much of the feedback I got about my original BirdCam article included “why didn't you use motion?” Quite simply, I didn't have a computer nearby I could attach to a camera. Now I do. Like I mentioned earlier, I started with a Raspberry Pi. If you have simple needs, or a low-resolution camera, the RPi might be plenty of horsepower. Since the procedures are the same regardless of what computer you're using, just pick whatever makes sense for you.

Motion is a frustratingly powerful program. By that, I mean it will do so many things, it's often difficult to know where to begin. Thankfully, the default configuration file is commented really well, and very few tweaks are required to get things going. For my WindowCam, I have motion do three things:

Save a snapshot every second. This is for BirdCam, so that it can embed a thumbnail of WindowCam in the corner. (See Figure 1, with the huge Mourning Dove in the corner.)

When motion is detected, save full-resolution images, 15 frames every second. Note, this is a lot of photos, especially with a busy WindowCam. I easily get 100,000 photos or more a day.

Record videos of motion detected. I actually don't do this anymore, because it's hard to deal with hundreds of short videos. I just take the photos saved in step two and create a daily archival video (more on that later).

Motion will do much, much more. It will support multiple cameras. It can handle IP cameras. It can fire off commands when motion is detected (turn on lights, or alarms, or text you and so on). But I'll leave those things for BirdCam 3.0! Let's configure motion.

You want a camera that is UVC (USB Video-Compatible). It would be nice if cameras had a nice “USB Video-Compatible!” sticker on the box, but sadly, they never do. The good news is that many cameras are compatible, even if they don't brag about it. You can google for a specific camera model to see if other folks have used it, or you can check an on-line database before buying. See www.ideasonboard.org/uvc for a list of devices known to work, but if you're getting an off-brand model, you might just have to try it to find out. Interesting to note, if you see a “Certified for Windows Vista” sticker, the camera is UVC-compliant, as that's a requirement for Windows Vista certification.

I chose the Logitech C920 USB camera, which supports 1920x1080 (1080p) video at 30fps. By default, the camera autofocuses, which sounds like a great idea. Unfortunately, I found the camera almost never focuses on what I want, especially if it's very close to the camera, which the birds tend to be. If you have issues with autofocusing, you might want to try tweaking the camera on the command-line. I have the following added to my startup scripts to turn off autofocus, and I set the manual focus to just outside my window:

uvcdynctrl -s "Focus, Auto" 0 uvcdynctrl -s "Focus (absolute)" 25

You'll need to play around with the focus value to get it just right, but if your camera supports manual focus, you should be able to tweak it for sharp images that don't need to autofocus every time a bird lands.

Installing motion is usually nothing more than finding it in your repositories and installing. You'll probably have to edit a file in order to get it to start at boot (like the /etc/default/motion file in Ubuntu), but it's not too painful. It's important to understand a few things about the default config:

Usually the “root” folder motion uses by default is in the /tmp folder. This could cause issues on your system if you just leave it alone and let it run—it could fill your /tmp partition and make your system break.

Motion uses /dev/video0 by default. This is good, as it most likely is the device name of your USB camera. If you have a funky camera though, you might need to change the device setting.

When you make a change to the configuration file, you need to restart motion for it to take effect. That generally means running sudo service motion restart or something similar.

Next, open the config file (as root), and make some changes. I'll name the directive to search for below, then talk a bit about the settings. These configuration directives should all be in your /etc/motion/motion.conf file. You'll just need to modify these values:

width: I use width 1280 for my camera. Even though it supports 1080p, I actually only record at 720p (1280x720). It saves space and still produces HD quality content.

height: in order to get the proper aspect ratio, I set this to height 720. Note, my camera will take photos only with the 16x9 aspect ratio, even if I set it to something else.

framerate: this is how many frames are captured per second. I use framerate 15, which provides fairly smooth motion while saving the most disk space. With the Raspberry Pi, I could get around 5fps with a 640x480 camera before the CPU load maxed out.

threshold: this is how many pixels must change before the program triggers a motion event. I left the default, then tweaked it later. My setting currently is threshold 2500.

minimum_motion_frames: by default, this is set to 1. I found that occasional camera glitches would fire off a motion event, even if nothing moved. Setting this to 2 or 3 will make sure there's actual motion and not a camera glitch. Mine is minimum_motion_frames 2.

quality: the default quality of 75 is probably fine, but I really wanted a sharp image, especially since I spent almost $100 on a camera. I set this to quality 95.

ffmpeg_cap_new: this is the setting that will tell motion to record videos. I had this “on” at first (it defaults to “off”), but I ended up with hundreds of short little videos. If you turn it on, fiddle with the other ffmpeg options as well.

snapshot_interval: this will capture a single image every N seconds. I have it set to snapshot_interval 1 and use the image for embedding into BirdCam.

target_dir: this setting is very important. This directory will be the “root” directory of all files created by motion. Both photo and video files are kept in this directory, so although using the ramdisk might sound like a good idea, it probably will fill up quickly.

snapshot_filename: this will be the periodic snapshot filename. I set it to a single filename so that it is overwritten constantly, but you can leave it with the datestring stuff so it will keep all the files. This filename is relative to target_dir, so if you try to set an absolute path, it still will be relative to target_dir. You can, however, add a directory name. On my system, target_dir is /home/birds, and I have a symbolic link inside /home/birds named ram, which points to a folder inside the /dev/shm ramdisk. I then set snapshot_filename ram/windowcam, and it overwrites the windowcam.jpg file in my ramdisk every second. This saves wear and tear on my hard drive.

jpeg_filename: this directive is similar to snapshot_filename, but instead, it's where the 15 images per second are stored. This is one you don't want to redirect to a ramdisk, unless you have an enormous ramdisk. I kept the default string for naming the files. My setting puts the photos in a separate folder, so it looks like this: jpeg_filename photos/%Y-%m-%d_%H.%M.%S-%q.

movie_filename: this is what determines the name and location of the ffmpeg videos. I'm not saving ffmpeg videos anymore, so my setting is moot, but this is where you assign folder and name location. Even though mine isn't used anymore, my setting from when I did record video is movie_filename movies/%Y-%m-%d_%H.%M.%S.

webcam_port: by default, this is set to 0, which means the Webcam is disabled. On a Raspberry Pi, I don't recommend turning this on, but on my Intel i5-based system, I have it set to port 8081. It creates a live MJPEG stream that can be viewed from a browser or IP camera-viewing software (like from an Android tablet).

webcam_maxrate: this determines frames per second. I have this set to 10, which is fast enough to see motion, but it doesn't tax the server.

webcam_localhost: by default, this is set to “on”, which means only the localhost can view the Webcam stream. If you want to view it remotely, even from other computers on your LAN, you'll need to change this to “off”.

Although that seems like a huge number of options to fiddle with, many of the defaults will be fine for you. Once you're happy with the settings, type sudo service motion restart, and the server should re-read your config file and start doing what you configured it to do.

I probably could talk about the fun things I do with my BirdCam server for two or three more articles. Who knows, maybe I'll visit the topic again. Before I close this chapter though, I want to share a cool thing I do to archive the bird visits for a given day. I mentioned that I end up with more than 100,000 photos a day from detected motion, and quite honestly, looking through that many photos is no fun. So at the end of every day, I create an MP4 video using the images captured. I've tried a few different tools, but the easiest to configure is mencoder. If you get mencoder installed (it should be in your repositories), you can turn those photos into a movie like this:

mencoder "mf:///home/birds/photos/*.jpg" \ -o /home/birds/archive/`date +"%Y-%m-%d"`-WindowCam.avi -fps 15 \ -ovc lavc -lavcopts vcodec=mpeg4:mbd=2:trell:vbitrate=7000

I run that command from cron every evening after sundown. Then I delete the images, and I'm ready for the next day. What I end up with is a 2–3 hour video every day showing all the bird visits at my window. It might seem like a lame video, but I usually scrub through it the next morning to see if there are any new or exotic birds visiting. The videos are 4–6GB each, so if storage space is an issue for you, it's something to keep in mind—which brings me to the next, and final, cool addition to BirdCam.

I want to be able to watch my archived video from anywhere. It's possible to stream my local media via Plex or something direct like that, but it would mean I had to connect to my home network in order to see the birds. Now that YouTube has removed the 10 or 15 minute limit on YouTube accounts, it means I can upload a three-hour archive video of birds at my window to YouTube, and have them store and display my video in the cloud—and for free!

Because this is Linux, I wanted to find a way to script the uploading and naming of my daily video. Thankfully, there's a really cool program called ytu, which stands for YouTube Uploader. It's simple, but very powerful. Download it at tasvideos.org/YoutubeUploader.html.

The most difficult part of running ytu is that you need a developer key. You can become a developer and get a developer key at https://code.google.com/apis/youtube/dashboard/gwt/index.html. It's not difficult, but the URLs keep changing, so I can't give you a more specific link. Once you have your developer key (a long string of letters and numbers), you can fill out the credentials.txt file with:

Google e-mail address.

Google password in plain text.

Developer key.

Make sure only the account executing the ytu binary has access to the file, as your password is stored in plain text. If this security problem isn't acceptable, you can, of course, upload videos to YouTube manually. I actually have a separate Google account for uploading BirdCam videos, so I'm not as concerned with the security.

Once the credentials file is set, you invoke ytu from the command line, or in my case, from the same cron job that creates the video. After the video is created, I immediately start ytu to upload it to YouTube. After several hours of uploading and processing, the video is ready to watch. If you'd like to see my archived videos, just surf over to snar.co/windowcam and see all the past videos.

Obviously, I have a mild obsession with birdwatching. We all have our quirks. With this article, and my last BirdCam article, hopefully you can figure out a way to adapt the power of Linux to scratch that video-capturing itch you have. If you do end up with something similar, or even something drastically different (dogcam on the local fire hydrant?), I'd love to hear about it! Well, maybe not the fire-hydrant cam...that's a little too strange, even for me.