If you're sick of big, clunky sound editors and minimalist, feature-lacking editors, EKO may well strike the balance you're looking for. According to the Web site:

EKO is a simple sound editor. EKO understands all popular sound formats (except MP3) and is useful in simple editing (cut/copy/paste) with minimal FX processing. External FX currently are not supported.

Installation

At the time of this writing, only the source was available—no binaries. But, fear not; installing by source isn't hard.

Regarding library requirements, according to the documentation, you need Qt 4.x, libJACK, libsndfile and libsamplerate. Although this is true, as is always the case with source, you also need to install the -dev development packages in order to compile the source code.

Once the dependencies are out of the way, install EKO with the following commands:

$ qmake $ make

If your distro uses sudo (such as Ubuntu), enter:

$ sudo make install

If your distro uses root, enter:

$ su # make install

Once the installation has finished, you can run EKO with this command:

$ eko

Usage

Inside the EKO screen, things actually are pretty easy and intuitive, and EKO's main features are obviously placed. Right from the get-go, EKO is ready to open a sound file and start editing, and rather tellingly, the FX rack also opens at startup (an instant picture of the author's feature wishes and EKO's design principles).

Click Open file on the main toolbar, choose an audio file to edit, and let's explore EKO's features.

With a sound file on-screen, the obvious Start and Stop controls are in a bold purple, with a check box for looping on their left. Click anywhere on the wave, and you can play from there, select a section and loop it, and so on. However, the interesting bit is the FX rack window on the right.

As you're no doubt aware, EKO uses Jack for its audio interface, and the effects in the FX rack need Jack to operate. However, keen observers will notice that at no time have I mentioned starting Jack in the instructions. As it turns out, EKO actually starts Jack for you with its default settings, if it's not already running (thankfully, you also have the choice of running Jack with your own settings before starting EKO, after which EKO skips the Jack step).

Although the FX rack was quite limited at the time of this writing (only four effects in total: amplification, EQ, overdrive and pitch shifting), author Peter Semiletov has chosen wisely in implementing perhaps the most useful features before expanding EKO's capabilities. While using Jack with effects generally involves some complicated routing, EKO's use of its current effects already has the routing done for you.

If you want to immerse yourself more within the screen, you can choose View→Toggle fullscreen. If the color scheme is throwing you off, check out the palettes in the view menu (winter is my favorite choice).

If you want to tweak your settings further, look to the right of the window, and you'll see four tabs. Click on tune. For the more superficial aspects, you can change the UI settings, such as font, icon size and window styling under the Interface tab. However, more important settings are in the other tabs, such as a large choice of keyboard shortcuts. Under the Common tab, you can choose the default format for new files and define the re-sampling quality for playback.

Eagle-eyed readers also will notice that EKO can down-mix 5.1 to stereo—perhaps this will be reason enough for many users to fire up EKO from time to time?

EKO is very speedy, and there is good reason for that: it loads the project files into RAM. Obviously, there's a cost for this speed. You'll need a lot of system RAM for this, and I assume larger projects will require something that uses the hard drive. It also seems to be an editing-only suite, not for recording, but who knows what direction it'll go?

Nevertheless, this early project shows a lot of promise as a genuinely fast, simple and usable editor that fills a niche between Goliaths like Ardour and simpler programs that are just too limited. I'll be interested to see where Peter takes it.

My last article covered the OLA lighting project with the Arduino RGB device, and because of some dependency problems at that time, I had to skip over the recommended QLC application and use the given Web interface.

However, now I'm delighted to say I've got QLC working without a hitch, and I cover it here (although I should mention, QLC is in no way connected with the Arduino RGB or OLA projects, but is for lighting in general).

According to the Web site:

Q Light Controller is a cross-platform application for controlling DMX or analog lighting systems like moving heads, dimmers, scanners and so on. The goal is to replace hard-to-learn and somewhat limited commercial lighting desks with FLOSS.

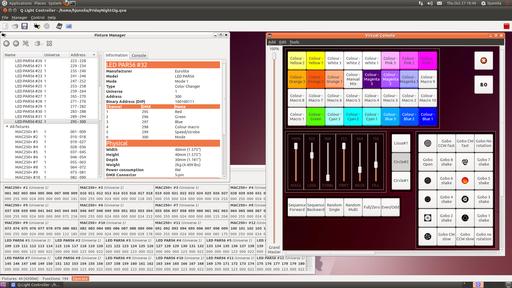

A preview shot of the upcoming QLC release in full flight—much more impressive than my lame demonstrations!

Installation

If you're chasing a binary, packages are provided for Debian, Ubuntu, Red Hat, Fedora and Mandriva. If you want (or need) to go with the source option, you first need to install Subversion, as that is the given option for attaining source with QLC. As for library requirements, the documentation gives the following for Debian and Ubuntu: g++, make, libqt4-dev, qt4-dev-tools, libasound2-dev, libusb-dev, subversion, debhelper and fakeroot.

Ubuntu further requires: libftdi-dev and pkg-config.

Whereas Red Hat/Fedora users need: gcc-c++, qt4-devel, libftdi-devel, libusb-devel, alsa-lib-devel, rpm-build and subversion.

If you prefer the source, make a folder in which you want to build QLC, and then open a terminal in that new directory. Now, enter the following commands:

$ svn checkout https://qlc.svn.sf.net/svnroot/qlc/trunk/ qlc $ cd qlc $ svn update

A quick note: any Arduino RGB and/or OLA users will have to enable a plugin, which also requires using the source via svn. If you're pursuing this option, grab the source as above, and edit the plugins.pro file in the plugins folder.

Uncomment the following line by changing this:

#unix:SUBDIRS += olaout

to this:

unix:SUBDIRS += olaout

(Of course, all other users can ignore this section and continue.)

Now, to compile the program, enter:

$ qmake-qt4 $ make

To install QLC, if your distro uses sudo (such as Ubuntu), enter:

$ sudo make install

If your distro uses root, enter:

$ su # make install

To run the program, use this command:

$ qlc

(Note: OLA users should start olad before running QLC.)

Usage

Inside the program, QLC's interface is spread into five main sections: Fixtures, Functions, Outputs, Inputs and Virtual Console. To start using QLC, click on the Fixtures tab. Here in Fixtures, you tell QLC what lighting hardware you're using and define its parameters.

Like the giant text suggests, click the + button to add fixtures. This brings up a new window with an array of lighting fixtures from which to choose. My correspondent, Heikki Junnila, was using the Eurolite LED PAR56 model, which he set to Address 1, Universe 1, with Amount 1. With my humble little Arduino, the model was Generic→Generic, which was set to Universe 1, Address 0, and the Channels were set to 6 (the number of lights I had attached to the board).

With the fixtures defined, it's time to interact with the hardware by making a scene.

Click on the Functions tab, and in the Functions toolbar, you'll see a series of new icons. Click the button on the left, New scene, and a new window appears. Click the + button and choose the fixture to be used (likely just one if it's your first time). Back in the scene window, you probably should enter a name in the given field before proceeding further. But, to do something interesting, click on the second tab, which will be named after the fixture type (“Dimmers” in my case).

Here you can play with your lighting device in real time, experimenting with the look of a scene, then committing the lighting scene later. Back in the General tab, if you look down at the bottom of the window, there are some lovely Fade In and Fade Out options, which I promise will look fantastic if you try them.

While I've shown you how to make one scene, you should repeat the same steps for a second scene, but with different values (perhaps activating different lights or different levels). This way you can explore the Chaser function with an obvious visual transition to show off its abilities.

What is this Chaser function, you ask? Basically it's the means to string together your scenes. With functions, such as looping and sequences, chasers are really what turn your scenes into an actual show.

To use them, simply head back to the window where you made the scenes, and on the toolbar, click the next button along from New scene (yes, the little green arrow in the orange ball), and this brings up the Chaser editor.

In the new window, first give your chaser a name. Now, press the + button, choose the scenes you want to add, and click OK. Back in the Chaser editor window, you can dictate how the whole sequence works, right down to the order in which the scenes run, whether they loop or play once through, and the duration. This window is really where the design aspect comes to the fore.

As I'm running out of space, let's jump to the Virtual Console, where I guess you could say the live direction happens. The basic idea is that you place a button somewhere in the workspace and then link it to something like a scene, effect or chaser. This way, you can have a series of labeled buttons, so if you're lighting a stage play, for example, you can click a button to have specific lighting for one scene and then click another button to change the lighting for the next.

The first button on the toolbar makes the new button, placing it in the workspace below. Then, right-click the button and choose Properties. Here you do all of the usual stuff, like labeling the button, but most important, you need to choose the function it activates, and the icon with the attached plugs does this. Choose the functions you want to activate, click OK, and then click OK again in the Button window to head back to the main screen.

Now for one last instruction. If you left-click the button now, nothing will happen. See that big blue Play button above? Click that, and it switches QLC to Operate mode (it also changes to a Stop button, which switches back to design mode when you're done). Click your buttons now, and hey, presto, your lighting effects are running by your command!

Although total novices may find QLC to be hard to come to grips with initially, the interface is actually very well thought out, and after you've been through the process once, things should come to you intuitively. It also appears to be quite extensible in design, so I imagine it will become rather powerful as time goes on.

Hopefully, Q Light Controller eventually becomes the easy choice for anyone new to lighting, those on a budget, or maybe it even will persuade some away from their expensive proprietary software!