You may have heard of the recent security breach that took place on kernel.org. The attacker gained root access to the servers and modified a kernel source-tree release candidate, in the hopes of infecting lots of users.

Since then, the kernel.org system administrators have been working like mad, cleaning out the servers and implementing security measures that might hopefully prevent another attack. One such measure involves restricting access to kernel.org itself. In the past, people maintaining a git tree on kernel.org could get a shell account on that system. Those days are gone. H. Peter Anvin announced that the gitolite tool would be used to update git trees from now on, and shell access would no longer be handed out as freely as it was.

The kernel.org folks also are instituting a cryptographic “web of trust”, so that people maintaining a git tree will be able to establish their identity when doing updates. If you're a developer who hacks the kernel in your spare time or for your employer and typically submits patches via e-mail, you won't need to be part of the web of trust; in fact, your work flow can continue unchanged. Only folks involved in maintaining projects on kernel.org are affected by these new policies.

Linus Torvalds has expressed some doubt that cryptographic signatures are as important as others believe. He's said, “Realistically, I checked a few signatures this time around due to the kernel.org issues, but at the same time, the thing that made me trust most of it was just looking at commits and the e-mail messages—the unconscious and non-cryptographic 'signature' of a person acting like you expect a person to act.”

Andi Kleen has resubmitted his patch that makes 3.0 kernels pretend to be 2.6 kernels, so binary-only software expecting to run on a 2.6 kernel still will run correctly under 3.0 kernels. It's an ugly pill to swallow. This time around, Linus Torvalds asked which binary-only software actually was breaking under 3.0, and a number of people replied, listing off several applications. Some HP management tools were among them. There also were a lot of nonbinary applications, including a number of Python scripts that performed an incorrect test for the current kernel version number.

Linus seems very reluctant to adopt this patch, especially considering that Andi has stated positively it's not just a short-term fix, but that 3.0 kernels would have to continue to masquerade as 2.6 kernels for the long term, in order to maintain compatibility with those binary-only tools.

I've realized I've missed out on a huge area of computational science—chemistry. Many packages exist for doing chemistry on your desktop. This article looks at a general tool called avogadro. It can do computations of energy and gradient values. Additionally, it can do analysis of molecular systems, interface to GAMESS and import and export from and to several file formats. There also are lots of options for generating pretty pictures of your totally new molecule that you hope will revolutionize the chemical industry.

When you first start avogadro, it opens up a new project consisting of one tab for a view of the molecule. Within this window, you can create a molecule in several different ways. If you want, you can build your molecule step by step, one atom at a time. You can click on the pencil at the top or press F8 to select the draw tool. With this, you can click and drag to draw atoms and bonds. To select different elements or different bond types, click on the Tool Settings button to get a second panel with those options available. To draw, click with the left mouse button. To erase, click with the right mouse button.

You also have the option of building it up from molecule fragments. Under the Build menu item, select Insert→Fragment. This pops up a window where you can select from among molecule fragments, such as carboxylic acids, ketones, alkanes or amino acids. You even can build a buckminsterfullerene with a single click.

As you build up the molecule, it appears in the view window. You also can insert a fragment by entering a SMILES text string. SMILES is the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry Specification. Check the Wikipedia entry for more details on its format.

There is also a peptide builder under the menu entry Build→Insert→Peptide. This dialog window lets you build up a peptide by selecting the amino acids, the terminating fragments and the structure of the peptide. The available structures are straight chain, alpha helix and beta sheet.

You can make global adjustments to your molecule by adjusting the hydrogen bonds. You can do a global replacement of changing hydrogens to methyl groups. You also can change the number of hydrogen atoms based on the pH of the molecule.

You can save this molecule in several different formats, including CML, GAMESS Input, Gaussian Input, MDL SDfile, PDB, NWChem Input, Sybyl Mol2 and XYZ.

Once you are done building your molecule, one of the first things you may want to do is get an idea of what it actually looks like. As a first approximation, you can use the Optimize Geometry function, located under the Extensions menu item. This actually goes through your molecule and adjusts the bond lengths and the bond angles to optimize your molecule's physical geometry. You can select what force field is used to do this calculation. Under the menu item Extensions→Molecular Mechanics→Setup Force Field, a new window pops up letting you choose which force field you want to use, along with the number of steps to take, the algorithm to use (either Steepest Descent or Conjugate Gradients) and the convergence threshold. Depending on your molecule's complexity, some settings may work better than others. For example, the MMFF94(s) field is good for organic chemistry and drug-like molecules. If you try to optimize the geometry and get odd-looking results, checking these options should be your first step. You can see the calculation's progress by clicking on the Messages tab at the bottom of the window.

Once you have optimized your geometry, you can calculate your molecule's energy by selecting Extensions→Molecular Dynamics→Calculate Energy.

There is a limited amount that you can do directly in avogadro in terms of actual quantum-level calculations. But, that's okay, because lots of really good programs exist that already do that very well. You can use avogadro to output files that can be used by these other programs as input files to do such higher-level computations. Under the Extension menu item you will find entries to build input files for GAMESS, Gaussian, MOLPRO, MOPAC, NWChem and Q-Chem. Each of those entries pops open a new dialog window where you can select the extra options for the to-be-created input file. This includes things like the number of processors to use, the type of calculation to do or the theory to use, for example. A preview window shows you what this export file will look like, so you can be sure you're getting what you were expecting. Once you're happy, click on the generate button at the bottom of the window to generate the input file for the external program of interest.

Once these calculations are done, you can import them back into avogadro to do some analysis. You can import trajectory files or vibration files. Once that data is imported, functions are available to graph this data in order to extract information and see what's happening. For files that contain molecular vibration information, you even can graph the results as a movie. You have some options in terms of the frame rate and so on, and once you are satisfied, you can save it as an AVI file.

You also can import data from experiments too. When studying chemicals, one common experiment is to look at the spectra of the chemical of interest. To start, click on the menu item Extensions→Spectra. This pops open a new window in which to do the analysis. At the bottom of the screen, you can click on Load Data. This lets you import data in two formats: either PWscf IR data or Turbomole IR data. You can select how this data is displayed, including producing publication-quality graphics.

Hopefully, this short introduction gives you some ideas for getting started. Lots of other chemistry programs exist that you can look at to offer more functions and calculations. Now you're ready to go out and do some quantum chemistry.

We've covered the cross-platform video player VLC in past issues, but if you're an OS X user, it's often preferable to use QuickTime. Because it's built into the operating system, QuickTime integrates with almost every aspect of the system. Unfortunately, QuickTime has limited playback support. Enter Perian. Perian is an open-source plugin for QuickTime that gives the native player the ability to play most popular video formats. The Perian Web site lists the following supported formats:

File formats: AVI, DIVX, FLV, MKV, GVI, VP6 and VFW.

Video types: MS-MPEG4 v1 and v2, DivX, 3ivx, H.264, Sorenson H.263, FLV/Sorenson Spark, FSV1, VP6, H263i, VP3, HuffYUV, FFVHuff, MPEG1 and MPEG2 video, Fraps, Snow, NuppelVideo, Techsmith Screen Capture and DosBox Capture.

Audio types: Windows Media Audio v1 and v2, Flash ADPCM, Xiph Vorbis (in Matroska), MPEG Layer I and II Audio, True Audio, DTS Coherent Acoustics and Nellymoser ASAO.

AVI support for AAC, AC3 Audio, H.264, MPEG4, VBR MP3 and more.

Subtitle support for SSA/ASS, SRT and SAMI.

Is Perian better than VLC? No, it's not better or worse; it's different. If you want to play unsupported multimedia formats with Apple's QuickTime player, Perian can make that happen. If you'd rather use a completely open-source player application, VLC fits the bill. Either way, open source saves the day with the ability to play back just about any file you'd ever want to play. Check out Perian at www.perian.org.

If you use a dedicated e-reader to read Linux Journal every month, chances are you want to read other material on it as well. Thanks to a free service called Instapaper, if you have an e-reader like the Linux-powered Kindle, you can take your favorite Web articles with you on the go, even if your destination doesn't have Internet access!

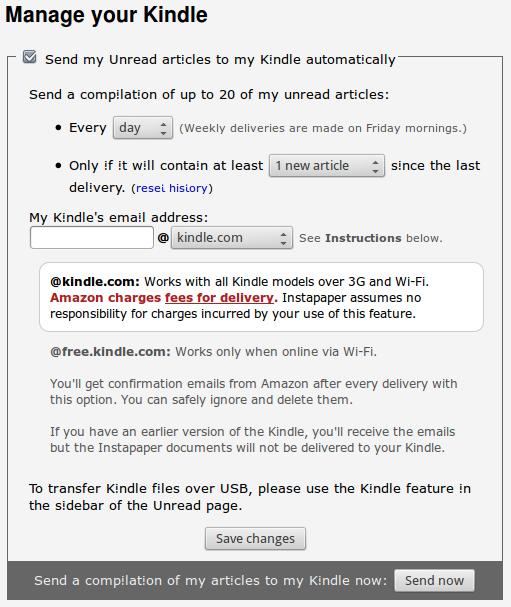

Instapaper works by giving you a bookmark to click any time you want to view a Web page later on your e-reader. Then, from your Internet-enabled mobile device, you can read the articles at your leisure. For those folks with a Kindle, Instapaper provides a free delivery service that sends batches of articles to your Amazon account. It's important to realize Amazon will charge you for 3G-based deliveries, but if your Kindle supports Wi-Fi, delivery is free as well.

Instapaper is great if you don't like to do the bulk of your reading in a Web browser, but still want to read the latest news from the Internet. The service is currently free, but you can become a subscriber for $1 a month and support the company. Instapaper is available at www.instapaper.com.

This past summer, I went to a beach resort in Mexico with my wife. It made sense to get into a little better shape so as not to cause any beached-whale rumors while I soaked in the rays. Typical geek that I am, I wanted to track my every move so I could see how much exercise I really was doing. And, I wanted to do that with technology.

Thankfully, RunKeeper is available for Android. RunKeeper is an exercise-tracking app that uses GPS to track your exercise. Thanks to geographical information over GPS, RunKeeper will track your distance, pace, time and even elevation. The free version provides lots of awesome features, and its social features also can help keep you accountable. (Although your Twitter followers might get tired of hearing about your daily walks to the park.)

Several other exercise apps are available, so if RunKeeper isn't your cup of tea, just search for “exercise” in the Marketplace, and you'll find a plethora of options. Keep in mind, however, that GPS-based exercise-tracking programs aren't much good in the northern winters, when running moves indoors to a treadmill.

Get the RunKeeper Android app at www.runkeeper.com/android.

If I'm not back in five minutes...just wait longer.

—Ace Ventura, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective

This is space. It's sometimes called the final frontier. (Except that of course you can't have a final frontier, because there'd be nothing for it to be a frontier to, but as frontiers go, it's pretty penultimate...)

—Terry Pratchett

I can picture in my mind a world without war, a world without hate. And I can picture us attacking that world, because they'd never expect it.

—“Deep Thoughts” with Jack Handey

Fantasy is the impossible made probable. Science fiction is the improbable made possible.

—Rod Sterling, The Twilight Zone

There's that word again, “heavy”. Why are things so heavy in the future? Is there a problem with the earth's gravitational pull?

—Emmet Brown, Back To The Future

This month, we bring you the results of 2011's Linux Journal Readers' Choice Awards. Every year, the awards give our readers the opportunity to support their favorite open-source software, development tools, languages, hardware and more.

It also gives readers an opportunity to discover new and popular technologies they may have not yet explored. To that end, I encourage you to check out some of this year's winners at LinuxJournal.com.

You consistently demonstrate your love for Python. These articles are a great place to read more:

“Python for Android”: www.linuxjournal.com/article/10940.

“Python Programming for Beginners”: www.linuxjournal.com/article/3946.

“Tech Tip: Really Simple HTTP Server with Python”: www.linuxjournal.com/content/tech-tip-really-simple-http-server-python.

Interested in Git for version control? Try: “Git—Revision Control Perfected”: www.linuxjournal.com/content/git-revision-control-perfected.

If you're into Puppet, “Automate System Administration Tasks with Puppet” is an oldie but goodie: www.linuxjournal.com/magazine/automate-system-administration-tasks-puppet

If HTML5 is your thing (and why wouldn't it be?), we have several great articles for you. Start with “Augmented Reality with HTML5” at www.linuxjournal.com/article/10920, and then do a quick search for HTML5 to pull up several gems.

You seem far more enthusiastic about GNOME 3 than our on-line columnist Michael Reed, so please feel free to discuss it with him in the comments to his article “GNOME 3.2 More Evolution than Revolution” at www.linuxjournal.com/content/gnome-32-more-evolution-revolution. Be nice though. We like Michael!

Many Linux users who have been GNOME fans for years find themselves in a sudden quandary. GNOME 3.0 has completely abandoned the desktop experience we've come to love during the years. That's not to say change is bad, it's just that many folks (even Linus Torvalds) don't really want to change.

As an Ubuntu user for several years, I'm accustomed to how well Canonical makes Linux on the desktop “just work”. Unfortunately, Ubuntu's alternative to the GNOME 3 switch is Unity. I want to like Unity. I've forced myself to use it to see if it might grow on me after a while. It hasn't. And, to make matters worse, version 11.10 won't have a classic GNOME option, which means I either need to bite the bullet and get used to Unity or go with an alternative.

Thankfully, XFCE has all the features I love about GNOME. No, XFCE isn't exactly like GNOME, but it feels more like GNOME 2 than GNOME 3 does! If you are like me and desperately want to have the old GNOME interface you know and love, I recommend checking out Xubuntu (the version of Ubuntu that uses XFCE). With minimal tweaking, it can look and feel like GNOME 2. Plus, XFCE has the ability to start GNOME (or KDE) services on login, which means GNOME-native apps usually “just work”.

The time may come when we're forced to adopt a new desktop model. For the time being, however, alternatives like XFCE or even LDXE offer familiar and highly functional desktop experiences. If you fear GNOME 3 and Unity, try XFCE. Download Xubuntu and check it out: www.xubuntu.org.