Your data isn't safe on public networks. You may not even realize the extent to which that statement is true.

Imagine this: you're sitting in your local coffee shop sucking down your morning caffeine fix before heading into the office. You catch up on your work e-mail, you check Facebook and you upload that financial report to your company's FTP server. Overall, it's been a constructive morning. By the time you get to work, there's a whirlwind of chaos throughout the office. That incredibly sensitive financial report you uploaded was somehow leaked to the public, and your boss is outraged by the crass and unprofessional e-mail you just sent him. Was there some hacker lurking in the shadows that broke into your company's network and decided to lay the blame on you? More than likely not. This mischievous ne'er-do-well probably was sitting in the coffee shop you stopped at and seized the opportunity.

Without some form of countermeasures, your data isn't safe on public networks. This example is a worst-case scenario on the far end of the spectrum, but it isn't so far-fetched. There are people out there who are capable of stealing your data. The best defense is to know what you can lose, how it can get lost and how to defend against it.

Packet sniffing, or packet analysis, is the process of capturing any data passed over the local network and looking for any information that may be useful. Most of the time, we system administrators use packet sniffing to troubleshoot network problems (like finding out why traffic is so slow in one part of the network) or to detect intrusions or compromised workstations (like a workstation that is connected to a remote machine on port 6667 continuously when you don't use IRC clients), and that is what this type of analysis originally was designed for. But, that didn't stop people from finding more creative ways to use these tools. The focus quickly moved away from its original intent—so much so that packet sniffers are considered security tools instead of network tools now.

Finding out what someone on your network is doing on the Internet is not some arcane and mystifying talent anymore. Tools like Wireshark, Ettercap or NetworkMiner give anybody the ability to sniff network traffic with a little practice or training. These tools have become increasingly easy to use and continue to make things easier to comprehend, which makes them more usable by a broader user base.

Now, you know that these tools are out there, but how exactly do they work? First, packet sniffing is a passive technique. No one actually is attacking your computer and delving through all those files that you don't want anyone to access. It's a lot like eavesdropping. My computer is just listening in on the conversation that your computer is having with the gateway.

Typically, when people think of network traffic, they think that it goes directly from their computers to the router or switch and up to the gateway and then out to the Internet, where it routes similarly until it gets to the specified destination. This is mostly true except for one fundamental detail. Your computer isn't directly sending the data anywhere. It broadcasts the data in packets that have the destination in the header. Every node on your network (or switch) receives the packet, determines whether it is the intended recipient and then either accepts the packet or ignores it.

For example, let's say you're loading the Web page http://example.com on your computer “PC”. Your computer sends the request by basically shouting “Hey! Somebody get me http://example.com!”, which most nodes simply will ignore. Your switch will pass it on to where it eventually will be received by example.com, which will pass back its index page to the router, which then shouts “Hey! I have http://example.com for PC!”, which again will be ignored by everyone except you. If others were on your switch with a packet sniffer, they'd receive all that traffic and be able to look at it.

Picture it like having a conversation in a bar. You can have a conversation with someone about anything, but other people are around who potentially can eavesdrop on that conversation, and although you thought the conversation was private, eavesdroppers can make use of that information in any way they see fit.

Most of the Internet runs in plain text, which means that most of the information you look at is viewable by someone with a packet sniffer. This information ranges from the benign to the sensitive. You should take note that all of this data is vulnerable only through an unencrypted connection, so if the site you are using has some form of encryption like SSL, your data is less vulnerable.

The most devastating data, and the stuff most people are concerned with, is user credentials. Your user name and password for any given site are passed in the clear for anyone to gather. This can be especially crippling if you use the same password for all your accounts on-line. It doesn't matter how secure your bank Web site is if you use the same password for that account and for your Twitter account. Further, if you type your credit-card information into an unsecure Web page, it is just as vulnerable, although there aren't many (if any) sites that continue this practice for that exact reason.

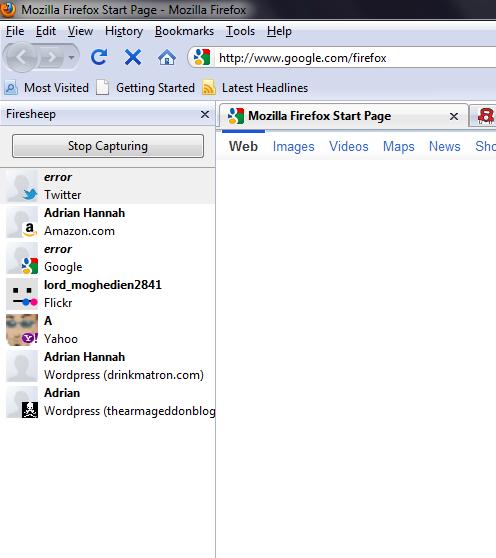

There is a technique in the security world called session hijacking where an attacker uses a packet sniffer to gain access to a victim's session on a particular Web site by stealing the victim's session cookie for that site. For instance, say I was sniffing traffic on the network, and you logged in to Facebook and left the Remember Me On This Computer check box checked. That signals Facebook to send you a session cookie that your browser stores. I potentially could collect that cookie through packet sniffing, add it to my browser and then have access to your Facebook account. This is such a trivial task that it can be scripted easily (someone even has made a Firefox extension that will do it automatically), and there still aren't many Web sites that encrypt their traffic to the end user, making it a significant problem when using the public Internet.

Figure 3. A Firefox Extension Designed to Gather Unencrypted Session Cookies from the Network

Packet sniffers exist that are specifically designed for monitoring what you are up to on the Internet. They will rebuild the exact Web page you are looking at, photos you're browsing, videos you're watching, and even files you're downloading. These applications are tailored to look through a string of packet captures to find various packet streams and reassemble them on the fly. My roommate in college whipped up something that would display the contents of my browser in real time on his computer (a scary revelation indeed).

E-mail is another one of those things that people tend to get up in arms about because there's an assumption of privacy in e-mail that is derived from the regular mail system. Your e-mail is sent out and viewable, just like anything else that emanates from your computer of the network. E-mail sniffing is what made the FBI's Carnivore program so infamous.

Since every packet bears a destination address in its header, it's possible that someone could sniff the network just to gather a browsing history of everyone on that segment. This may not be very insidious, but it's gathered data, and there's always someone willing to pay for all sorts of data.

I'm sure you're currently seconds from taking a pair of scissors to your network cable and swearing off the Internet for life, but fear not! There are less-drastic measures you can take to prevent such sensitive data loss. None of these precautions is the magic cure for eavesdroppers, but using even one of them will make you a less-desirable target. There's an old joke that says that when you're being chased by a bear, you don't need to outrun the bear, just the guy in front of you. You don't have to have the most secure computer on the block, just more secure than somebody else's. As with most network security, if people really want your data, they can get at it. However, most of the time, attackers aren't targeting a specific person, they're looking for targets of opportunity, so the more secure you are, the less likely you are to be such a target.

The first defense against eavesdropping is the Secure Socket Layer (SSL) used by most Web pages that handle sensitive information. This forces all the content shared back and forth between you and the site to be encrypted. Some sites use SSL for their login pages only. Most sites don't even use SSL at all. It's easy to tell—the URL in the address bar will start with https instead of http. Some sites offer you some choice in the matter. For instance, Google allows you to turn SSL on all the time within Gmail, thus encrypting all your e-mail traffic.

Modern network switches are designed to pass data intelligently to avoid packet collisions and excessive network traffic. If a packet is broadcast that is not intended for one of the nodes attached to it, the router will not rebroadcast to the local nodes. Likewise, if a packet is broadcast locally that is intended for another local node, the switch will not rebroadcast to the outside network. This forces strict segmentation on a network. For us, this means that someone using a packet sniffer on a switched network will not see any traffic from hosts not attached to the same switch. This doesn't mean much on small-scale networks, like you have at your house, but on a larger scale, it means that somebody can't sit in the breakroom sniffing traffic three floors up from the accounting department.

Wireless network encryption has come a long way in its short lifespan—going from no encryption to Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) encryption to Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) encryption. Wireless networks don't provide the same segmentation that the previously mentioned switches provide, meaning that any packet transmitted on a wireless access point gets rebroadcast to everyone else on the access point. Even though your traffic is encrypted under WEP, this encryption protects only the data from users not connected to that wireless network. The encryption scheme and key are identical for all users, so all your “encrypted” data is decryptable by anyone on the network, making your data essentially unencrypted. WPA solves this issue by isolating all users on the network and giving them a different encryption scheme even when the key is the same.

If you have SSH access to a computer outside your current network (which I'm sure most of us do), you can tunnel all your traffic through an SSH connection. You essentially are using the encryption of the SSH connection to protect all your data from eavesdroppers. There are two apparent downsides to this technique. First, you're connection speed will drop, because now instead of going from you to the destination and back, your traffic will go from you to the SSH server to the destination and back. Second, your data is transmitted unencrypted from the remote end, so if that machine is vulnerable to packet sniffing, your data is no safer than it was at your local machine.

Virtual private networks are intended to allow users access to a network that otherwise would be inaccessible. However, they also can be used to protect your traffic, because VPN connections are encrypted. You can set up a private VPN for yourself just for this purpose, but it will have the same disadvantages as SSH tunneling. If you work for a company that has a VPN, you may be allowed to use it for this purpose, but your traffic will fall under the same policy and rules that you have in your office, so be careful what you use it for.