Think Java's the only game in town when it comes to programming Android apps? Think again.

Mobile app development for smartphones is hot. This is no more prevalent than in the Android space where the activity level oftentimes is frenzied. However, when it comes to building a “real” Android app, it seems there's only one programming choice: Java (although it is possible with a lot more work to use C/C++ with Android's Native Development Kit). That said, Google wisely chose the popular Java programming technology upon which to base its Android SDK, which runs a customized VM.

By and large, this has been a smart strategy, as (unlike another popular smartphone) there's no need to own specific hardware and software to get started with app development on Android. All you need is a PC (or laptop) running Linux, Windows or Mac OS X, together with a copy of Java and the free Android SDK. Google provides emulator downloads for all the Android platform releases, and there's even a free plugin for Eclipse to start you off and point you in the right direction.

That's great—assuming, of course, you're a fan of Java. If, like me, you'd rather eat glass than sit down to write some Java code in Eclipse, it would appear that you are out of luck when it comes to implementing your next project on Android. But, this is not the case. There's a rather wonderful project called the Scripting Layer for Android (SL4A) that is bringing scripting languages to the Android platform and providing a working alternative to Java development.

In this article, I walk through the steps involved in preparing your computer for Android development with SL4A, then show how to write, test and run a simple script written in Python on your Android device.

The Scripting Layer for Android is one of the many projects to see life as a direct result of Google's policy of allocating 20% of its employees' time to “pet projects”. Damon Kohler works for Google, and he created SL4A to scratch his own itch when it came to programming Android. SL4A provides a high-level interface to Android's underlying Java technologies, exposing a subset of the API to scripting languages.

Python was one of the first languages to be supported on SL4A, but contributed interpreters also are available for Perl, JRuby, Lua, BeanShell, JavaScript and Tcl. In its default state, SL4A comes pre-installed with a working version of the shell. SL4A's API is designed to be portable across scripting languages, so if you like what you see in this article but wish I'd used Perl instead of Python, the API calls I use here should work exactly as shown with the Perl interpreter. It's true that I'm very much a fan of Perl, but I'm equally comfortable in Python, and, as Python is the SL4A “standard”, I stick with Python throughout this article. Just be aware that you don't have to.

To get started, you need a copy of the Android SDK running on your computer, and you need a Java VM. Although you aren't going to program your Android app with Java, you still need a Java runtime upon which to execute the Android emulator, which is part of the SDK. The inclusion of the Android emulator gives you a sandboxed testbed to play in while you create your app.

Before proceeding, you need to make sure a Java VM is installed on your Linux system. On my system (running a recent Xubuntu), I entered the following commands and was told neither program was available to me:

$ javac -version $ java -version

Xubuntu suggested that I might like to use apt-get to install openjdk-6-jdk, which sounded reasonable to me, so that's what I did:

$ sudo apt-get openjdk-6-jdk

If you are running a distro that's not derived from Debian, search your software repository for a similar package and install it before proceeding.

With Java in place, it's now time to get the Android SDK. Downloads of the SDK are available for Mac OS X, Windows and Linux. Pop on over to Google's Android Developer site (see Resources) and grab the latest SDK tarball for Linux.

With the SDK downloaded, simply unpack the tarball within a directory of your choice (the filename you have may be different from the one I use here, but don't worry, yours is likely a later version of the SDK):

$ tar zxvf android-sdk_r07-linux_x86.tgz

This command created a new directory called android-sdk-linux_x86, which I renamed to Android. This newly created directory has a bunch of subdirectories within it. Don't be overwhelmed by all the stuff that's in there. Only one subdirectory is of interest to you at this stage, and it's called tools.

Within the tools directory, only two programs are of interest to you. The adb utility allows you to transfer files to (and from) your Android emulator (more on this utility later). The android tool lets you prepare and run an emulator for any number of the current Android releases, and that's what you do next:

$ cd Android/tools $ ./android

The android command starts the Android SDK and AVD Manager, which is a tool that creates Android emulators for any number of Android virtual devices. At the moment, there are no virtual devices, so you need to create one. However, before this can happen, you need to install a target Android API package. To do that, click on the Installed Packages tab, then press the Update All button. In the dialog that appears, click Accept All and then press the Install button.

The resulting download takes a while, so drag yourself away from your computer and head off into the kitchen to make a nice cup of coffee. Depending on your download speed, you may have time to make a quick sandwich too.

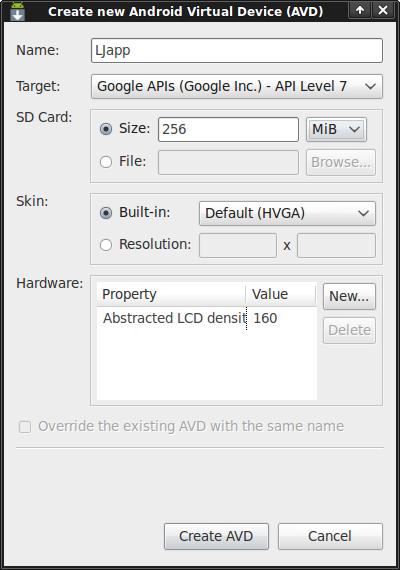

With the download(s) complete, let's create an Android Virtual Device (AVD). An AVD is a virtual version of an Android device that you can run on the emulator. Select the Virtual Devices tab, then click on the New button. A dialog appears that you can use to set the characteristics of your AVD. Figure 1 shows that I've given my AVD a name (LJapp), selected an API target (API Level 7, which is Android 2.1) and set my virtual SD card to 256 meg. When you have made your selections, click on the Create AVD button to initialize your AVD.

Figure 1. Setting the defaults for your emulated Android virtual device.

If you return to the Virtual Devices tab, your LJapp AVD now should exist. Select the AVD and press the Start button, then select the Launch button from the displayed dialog. The emulator starts to load, and after a few seconds, you see the opening screen for your emulated Android device (Figure 2). Note that the emulator runs much more slowly than the actual physical phone, so it may take a while to get to the Android startup screen. Your mileage will vary, depending on the speed of your desktop's processor.

Note: throughout the remainder of this article, I use the word “tap” to refer to using the mouse to click within the emulator. There is no mouse pointer on your physical Android device (that's what your finger is for), but the emulator needs something, so the mouse pointer “emulates” your finger, hence the use of the word tap to describe the action required. When you see me use the word tap, think click.

Getting the SL4A on your emulator is straightforward. Start by tapping the Android browser and surfing to the SL4A Web site: code.google.com/p/android-scripting.

When the SL4A Web page appears, tap on the square graphic (the QR Code) to access the download URL for SL4A. The download should begin immediately, and once it completes, tap the downloaded package name (which is sl4a_r3.apk at the time of this writing) to install SL4A. Go ahead and tap on the Install button, then tap on the Open button to start the app. You'll be asked to participate in usage tracking (it's up to you, and it's optional), and then SL4A informs you that you have “No matches found” under your Scripts listing. That's okay; you've yet to install any scripts. SL4A now is ready for Python.

Return to the Android browser and double-tap the screen to enlarge the Web page. Locate the Featured Downloads part of the page on the right, and tap on the download arrow beside the python_for_android_r1.apk link. As before, let the download complete before tapping on the downloaded file to install it. When you're ready, tap the Install button to confirm the installation of the interpreter. When this completes, tap on the Open button, then tap on the big Install button to complete the installation. The Python for Android app downloads, extracts and installs the Python support files from the SL4A Web site and adds them into SL4A. The entire process should take only a minute or two to complete. If it takes longer than a few minutes, take a deep breath, and remember that the emulator is much slower than your physical device.

When the installation completes, you'll be presented with an Uninstall button. Don't tap this button! If you do, you'll remove the Python interpreter that you've just installed. Instead, tap on the emulator's home button (the little house icon) to return to the Android main screen, tap the tab at the bottom of the screen to see the list of installed apps, and note that SL4A has been added to your emulator (Figure 3).

Go ahead and tap the SL4A icon that now displays the list of installed Python scripts. Tapping the hello_world.py script pops up the SL4A run menu (Figure 4). Looking from left to right, the menu icons have the following meaning: 1) run the script at the Python shell, which is useful when debugging; 2) run the script “natively”; 3) edit the script in SL4A's built-in text editor, which is useful only for the most trivial of changes; 4) rename the script; and 5) delete the script. To test your installation quickly, tap the second menu icon, which I like to refer to as the “run wheel”. After a second or two, a message saying “Hello, Android!” appears on screen for a few seconds then disappears.

Figure 4. SL4A Menu Icons

If that worked, tap the test.py script, then tap the run wheel. This runs a longer-running script that showcases some of the facilities available to you as a Python programmer working on Android. Again, bear in mind that the emulator runs slowly, so be patient and wait for the various Android interface elements to appear.

Your Android emulator now is ready to run your custom Python script, so let's create one. Before you do though, note that the published SL4A API is a subset of the full Android API, so certain features either are not available, in the process of being made available or fully supported (see Resources for a link to the current list). Don't let this put you off. What's there is more than enough to produce usable Android apps in Python.

To get a feel for Python running on SL4A, let's port an existing script to the phone. The script in question is based on some code from Chapter 2 of O'Reilly Media's Head First Programming, which I cowrote with David Griffiths in 2009. This simple script connects to the Web site of a fictitious company called Beans'R'Us to grab the company's home page and extract the current price of coffee beans from the page's HTML. The code is straightforward, grabbing the HTML page from the server, searching for the pricing data, extracting it from the HTML page and then displaying it on screen:

from urllib import urlencode

from urllib2 import urlopen

pg = urlopen("http://www.beans-r-us.biz/prices.html")

text = pg.read().decode("utf8")

where = text.find('>$')

start_of_price = where + 2

end_of_price = start_of_price + 4

price = float(text[start_of_price:end_of_price])

print "The current price of coffee is:", price

This is Python 2 code, which is a deliberate choice, as the Python that comes with SL4A is the 2.6.2 release. To take this program for a spin, either load it into Python's IDLE tool or execute it from the command line:

$ python LJapp-cmd.py The current price of coffee is: 5.52

As you can see, this small script displays the currently published price of coffee beans.

Turning this script into an Android app is just a matter of deciding on the Android UI elements you want to use, as the core functionality does not need to change. The Python on SL4A is fully functional, so the facilities you are used to with standard Python also are available on your smartphone.

To make this script more Android-like, let's display a friendly message on startup as well as one on exit. The makeToast() API call provides this functionality.

The dialogCreateSpinnerProgress() API call lets you display an Android spinner dialog, assuming you then remember to call the dialogShow() API call to make it visible. Let's display a spinner prior to requesting the Web page from the Beans'R'Us server, then dismiss the spinner dialog with the dialogDismiss() API call, once we have the data processed. And, let's vibrate the phone at this point too, just for the fun of it.

To conclude the script, use the dialogCreateAlert(), dialogSetItems() and dialogSetPositiveButtonText() API calls to display the price of beans within an Android dialog. To exit, simply tap the OK button.

Here's the Python code from earlier with the calls to the SL4A API added in:

import android

from urllib import urlencode

from urllib2 import urlopen

app = android.Android()

app.makeToast("Hello from LJapp")

appTitle = "LJapp"

appMsg = "Checking the price of coffee..."

app.dialogCreateSpinnerProgress(appTitle, appMsg)

app.dialogShow()

pg = urlopen("http://www.beans-r-us.biz/prices.html")

text = pg.read().decode("utf8")

where = text.find('>$')

start_of_price = where + 2

end_of_price = start_of_price + 4

price = float(text[start_of_price:end_of_price])

app.dialogDismiss()

app.vibrate()

appMsg = "The current price of coffee beans:"

app.dialogCreateAlert(appMsg)

app.dialogSetItems([price])

app.dialogSetPositiveButtonText('OK')

app.dialogShow()

resp = app.dialogGetResponse().result

app.makeToast("Bye!")

Other than the addition of the Android UI code, no other changes are required to the code from earlier, other than removing the earlier script's call to print (which is no longer required).

To transfer your Python script to the emulator for testing, copy your code file into your Android directory, then use the adb utility within the tools directory to push your file to the SL4A scripts directory on the emulator:

$ tools/adb push LJapp.py /sdcard/sl4a/scripts 6 KB/s (748 bytes in 0.116s)

With the file transferred, check the list of scripts within SL4A and notice the addition of LJapp.py near the top of the list.

Go on, tap your app name, then tap the run wheel. After a moment, you should see the spinner dialog appear while your script contacts the Beans'R'Us Web site and requests the current price of coffee (Figure 5). Shortly thereafter, the current price appears in another dialog (Figure 6). Congratulations! The script has been ported to your Android virtual device.

To run a Python script on your physical Android device, install SL4A together with Python for Android on your handset, then transfer your script.

To install SL4A on your physical Android device, enable the Unknown Sources option in your device's Application settings. This setting is required to enable the installation of non-Market apps on your phone. With this done, you can follow the same steps you used when installing SL4A and Python on your emulator. To speed things up a little, install Barcode Scanner from the Android Market and use it to “read” the QR Codes from your desktop screen.

There are a number of ways to get your script onto a real phone. I've found the success of using something like Bluetooth connectivity or USB cabling arrangements can very much depend on the hardware on which you're running. What works on one handset, doesn't on another, and so on. Your mileage may vary depending on your actual device. When I need to transfer a file, I've come to rely on a solution that works no matter which handset I use (as long as the handset can talk to a local Wi-Fi network). What I do is switch on the OpenSSH server on my development PC running Linux, then use the AndFTP file transfer app on the handset to scp files from the desktop to the phone. AndFTP is available from the Android Market as a free download and installs in minutes. Once I connect to my desktop with AndFTP, I can navigate to a directory of my choice, mark the files that I want, then download them to my SD card on the handset.

AndFTP works well, and I've come to depend on it for all my Android file transfers (see Resources). Just be sure to transfer your scripts to /sdcard/sl4a/scripts on the phone to ensure that your script names appear within the SL4A list of scripts.

With your script file transferred to your physical device, start SL4A as before, tap your app's name and tap the run wheel. As expected, your app runs just as it did on the emulator, only faster! I haven't included a screenshot of the app running on a real phone for two reasons. First, it looks exactly the same as it did in the emulator, and second, it's running on your device, so you can take a look at it there!

There's one further kink to SL4A that might interest you. The project includes draft instructions on creating a standalone, downloadable Android APK package (see Resources). Once created, the APK file bundles your custom Python script with information that allows other Android users to install Python for Android automatically onto their handsets and then run your app from the smartphone's main menu of apps. Describing the process of creating the APK likely would take another article, so I leave it to the brave among you to try out the instructions on the SL4A Wiki. To see and learn a little about one such successfully created APK, check out Split Hitter on the Web (see Resources).

Programming your app in Java is not the only option on Android. With SL4A, very capable scripting languages come to Android, taking the platform to a new level of hackability. If you can, get involved. More people means more eyeballs, and more eyeballs means more help and more code. Official support from Google will come if enough programmers get involved, which can only help raise the project's profile within Google's HQ. SL4A is already a good project, and I can only imagine the great project it will be with “official status” bestowed on it by Google. Let's hope this happens sooner rather than later.

You can learn lots more from the wiki documentation hosted at the SL4A Web site. Be sure to browse the Tutorials section of the wiki for links to what others are doing with SL4A. There's also an active (and very friendly) SL4A mailing list that Damon uses to announce new versions, track feature requests, report patches and spread the word about SL4A. If you build an app for Android using SL4A, join the list, and I'll see you there.

The scripts for this article were tested on an Android Milestone handset running release 2.1 of Android OS. The handset was kindly supplied by The Institute of Technology, Carlow, in Ireland.