Configure your own custom desktop and plug it in to any PC to re-create your working environment wherever you go.

Most of us work with multiple Linux machines these days, and we are used to hopping between them. However, there are times when you want to separate your Linux desktop experience from your physical desktop PC. You would like a Linux desktop that lives on a USB key that you can move freely among PCs. To explain this better, let me describe two problems I've recently addressed with a small, portable Linux distro:

I don't always work from the same location. Carrying a portable laptop computer around is one way of having my Linux desktop wherever I need it, but another way is to have a small Linux desktop on my keyring. When I arrive at a new work location, I can plug the USB key in to any available PC, boot Linux quickly and continue working right where I left off. The live Linux on the key runs entirely in memory and uses the key for persistent storage. I don't need a lot of storage (most of my data lives in the cloud), but I do need to be able to use a unique set of application packages so I have the tools I need to do my work.

I have a Netbook that bit the dust a few months ago. The failure was in the hard disk, and this particular generation of Netbook uses a 1.6" hard disk. If you can find a replacement drive that size, the price is such that it's cheaper to purchase a new Netbook. I'd like to be able to run my Linux desktop even on this machine, which is otherwise a brick.

To address these problems, I needed a Linux distro with the following characteristics:

Small enough to fit on a USB key.

Bootable on a variety of machines (all PC architectures).

Ability to run in memory only, given target machines would all have 1GB or more.

Quick booting.

Application package compatibility with a major Linux distro.

So, why not just run a desktop distro from a USB stick? That, in fact, was my first solution, and most desktop distros make it really easy to create a live USB installation, including persistence to storage on the USB drive. For example, Ubuntu 10.10 (and every Ubuntu release since 9.04) comes with the usb-creator tool that creates a live USB installation for you given the related .iso file.

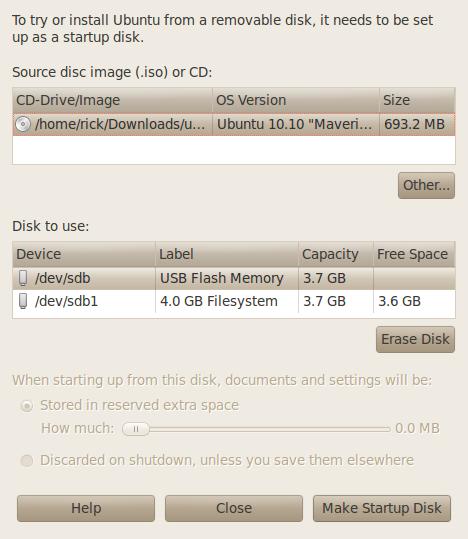

To create an Ubuntu 10.10 live USB installation, first download the .iso file for the desktop version from the Ubuntu Web site (www.ubuntu.com/desktop/get-ubuntu/download). After the download, plug in a USB stick (2GB or larger), and select System→Administration→Startup Disk Creator from the Ubuntu menu. Select the downloaded .iso and the target USB device—in the case shown here, it's /dev/sdb1. When you click Make Startup Disk, Ubuntu copies all the needed files to the stick and makes it bootable.

Figure 1. Make Startup Disk

You'll get a confirmation box, and then you've got your portable Ubuntu. If that meets your needs, you're all set. You can boot it on another machine, install applications using sudo apt-get install, and do pretty much anything you would do on your desktop, limited only by the available storage on the USB stick.

But, you may have needs that go beyond what you get with a standard off-the-shelf desktop. Because this is Linux Journal, you almost certainly have custom needs and preferences, and fortunately, there are ways to create your very own portable desktop distribution.

Puppy Linux, in particular, is built with customization in mind. If you've never heard of it, you may want to take a look at Louis Iacona's article “Puppy Linux” in the April 2008 issue (www.linuxjournal.com/article/9932). You also should visit www.puppylinux.com. Barry Kauler created Puppy Linux in 2003, and he has continued to develop it and build a community of developers for it since then. Lately, Barry has focused more on customization capabilities for the platform, resulting in the Woof tool, which builds Puppy-like distributions.

Puppy Linux has many other desirable features, including:

Runs entirely from memory, so it's very fast.

Very small memory footprint (100–110MB).

Support for a wide variety of hardware devices.

Compatibility with packages from other distributions (including Ubuntu).

User interface that's intended to be approachable.

There also are some features that might not be desirable, depending on your application:

Runs entirely in memory, so all active programs have to fit.

User runs as root, so there's the potential to screw up.

Hardware device support not as complete as major distros.

Even with the tools that Puppy Linux provides, building your own distribution isn't for the novice. You need to be comfortable using the Linux command line, have a suitable build environment and a broadband Internet connection. Additionally the tools still are under development, so expect that things are not entirely complete (such as reports and so on), and that some combinations of configuration choices just may not work yet. The best news is there's a very active community of Puppy and Woof users you can reach for help at puppylinux.org.

Building your distribution proceeds in five stages, with each stage having a number of steps:

Create a Puppy Linux host system. The Woof tool works only when run under Puppy Linux, so the first thing you need to do is create a host system that runs PL.

Use your PL host to download the Woof tool.

Use the woof_gui tool to configure the files that Woof will use to build your distribution.

Build your distribution.

Install your distribution on a bootable USB key.

Barry and the PL community have made this stage extremely easy. Simply download the latest Puppy Linux .iso file (LuPu 5.1.1 at the time of this writing) from one of the repositories listed on puppylinux.org, and write the .iso to a bootable CD. On Ubuntu, you can use System→Administration→Startup Disk Creator to burn the CD. For Windows, the PL site recommends the BurnCDCC utility.

Once you have your PL CD, you need to boot it on a Linux system. Puppy Linux runs completely from memory, but Woof needs 10GB of file space to do the build, so you'll want to use the underlying hard disk. Unfortunately, Woof works only with an ext3 or ext4 filesystem, so a Windows disk won't work for you. When PL boots, it should display a desktop and allow you to start the SNS utility to configure your network connection.

At this point, you could use the Puppy Linux Install utility (on the desktop) to create a PL USB key. If you like PL as it comes preconfigured, or just want to install a few additional applications from .deb packages, you can stop here, without going through the full build of a distribution. You also could install Puppy Linux to your hard disk if you want, but you don't have to.

PL comes with its own version control system called Bones. The first thing you want to do is create a directory called woof-tree somewhere on your hard disk. In the setup I used, PL sees my Linux hard disk as /dev/sda1.

Now you can open a PL terminal window (Menu→Utility→Urxvt terminal emulator), and note that you're running as root (#). In my setup, I cd'd to my Linux home directory and created woof-tree:

# cd /mnt/sda1/home/rick # mkdir woof-tree # cd woof-tree

Once that's done, you first tell bones which repository:

# bones setup

You can fill in anything you like for local_username; the Download URL is bkhome.org/bones/woof.

Now, enter:

# bones download

And, bones will do just that—download and unpack the current set of Woof files.

Once that's done, it's a good time to read the downloaded file README.txt, which you'll find in woof-tree. This file contains the latest information about the tools and also serves as the help file for the next stage.

Bones downloaded a number of files into woof-tree, including some configuration files with names beginning in DISTRO_, some other files and scripts, and six numbered scripts: 0pre, 0setup, 1download, 2createpackages, 3builddistro and 4quirkybuild, which isn't used for Puppy Linux builds.

You can edit the configuration files and use Woof from the command line to build your distribution, but I'll warn you that it's a bit daunting. Luckily, Barry and friends have provided a GUI interface to the build system that helps you through the process:

# ./woof_gui

The tabs at the top of this utility correspond to the steps in building a distribution. The tabs mirror the Woof configuration files and allow you to customize your distribution. To create your distribution, you move left to right through the tabs, making choices and executing the required builds.

The Specifications tab shows the high-level settings for the distribution to be built. At the time of this writing, woof comes preconfigured to build Wary, one of the derivatives of Puppy Linux. Notice the “Previous templates” section about two-thirds of the way down. From this pull-down, you can select a number of previously defined (and proven) build templates, which minimizes the choices you have to make and the possibility of specifying something that won't work. I chose “Ubuntu Lucid Lynx LuPu”. If you make changes, select UPDATE OVERALL SPECS at the bottom to update the corresponding configuration files. You may get some errors about missing files—at this point, all of those should be configured for loading when Woof does the build.

The next tab, PET repos, tells Woof where to find the PET packages and databases it needs for the build. PET is the native package format used by Puppy Linux and Woof. It is optimized so the packages are small and quickly loadable. Unless you want to add a PET package that isn't part of the standard Puppy PET repositories, you shouldn't have to change this tab. If you need to modify the list of repositories, click Edit, and you will be put into the text editor to edit the DISTRO_PET_REPOS configuration file. The Help: Repositories button will give you the format for the file. If you do make any changes, click UPDATE PET REPOS to save the updates.

The next tab, Compat repos, gives Woof the on-line locations for packages and databases compatible with the entry “Compatible-distro”, that you made on the Specifications tab. If you need to modify the list of compatible package locations, click the appropriate Edit button, and you will be put into the editor to edit the DISTRO_COMPAT_REPOS configuration file. Again, the format is available with the Help button, and if you make changes, you need to click UPDATE COMPAT-DISTRO REPOS to save them.

The next tab, Download dbs, executes the script (0setup) to download the PET and compatible package databases from the last two tabs. The top half of the tab shows the PET databases selected and those that are actually available locally. The bottom half does the same for compatible databases. If the selected and local lists do not agree (which is likely at this point), click on the UPDATE LOCAL DB FILES button, and the files will be downloaded. This can take a while to complete.

The next tab, Choose pkgs, is where you see the PET and compatible packages included in your build. There are separate buttons to edit the list of PET packages and the list of compatible distro packages, but at the time of this writing, these editors have not been implemented. No matter, you can change the package selection by directly editing DISTRO_PKGS_SPECS-<compatible distro>. The format of the file is given as a comment in the file itself. At the time of this writing, the CHECK DEPENDENCIES button also has not been implemented, so be sure the dependencies for any additions are included, so the build can complete successfully.

The Download pkgs tab executes the script (1download) that actually downloads the packages you specified for your distribution. Again, this takes a while. The script first checks to be sure the on-line package locations are reachable, then downloads each of the packages needed. Downloading can take several hours, so a small control panel dialog box pops up to let you pause, resume or quit the script. If a package already exists in the local location, it does not download again, so the script also can be used to restart a download or update the set of packages when a change is made. The REPORT feature on the tab is not yet implemented, but the results are in a file called DOWNLOAD-FAILS-PET or DOWNLOAD-FAILS-<distro> in the woof-tree directory.

Here is where you get to use your Linux deductive skills if there were any problems in downloading the packages. In my case, the download for AbiWord failed—the script was looking for a prebuilt PET package, abiword-2.8.3-lupu.pet. A quick grep of the Packages* files shows that the script expected to find it in puppy-5-official. Rerunning the Download, the problem is quickly apparent—abiword-2.8.3 fails to download because of a broken link, and discussions on puppylinux.org confirm that there are some issues with AbiWord packages. I could find the .pet or .deb packages and copy them in by hand, but to tell the truth, I don't need AbiWord in my distribution, so instead, I edited DISTRO_PKGS_SPECS-ubuntu-lucid and changed the abiword entry from “yes” to “no”. Download pkgs confirms that everything is successfully downloaded.

The Build pkgs tab executes the script (2createpackages) that takes the distro packages you downloaded (Ubuntu .deb packages in this example) and converts them to PET packages. At the end of this step, you have a complete collection of PET packages for your distribution.

Kernel options offers you a choice of Linux kernels and some options for paring down the kernel size. Depending on your concern about kernel size, your need for the specific modules mentioned and your willingness to experiment, you can choose whether to include them.

Build distro is the final tab that uses all of the collected configuration and packages to build your custom distribution. You get a chance to choose simplified filenames on this tab, but reading the quite thorough Help file, there doesn't seem to be a solid reason for doing so. Clicking on BUILD DISTRO starts the build. As the build proceeds, you are given some options (moving modules to a separate file to improve boot time, default theme, text shadowing, Xorg drivers and executable stripping). You can experiment or take the default (the prompts will tell you if the default is not safe). When the .iso file is complete, you have the option of burning a CD—you'll need it, even to make a USB key. Then, you're asked if you want to build a devx file, which you'll need if you plan to do compiles and builds with your distribution. When the script is done, you'll find your distro's .iso (and the .iso's MD5) in the directory sandbox3.

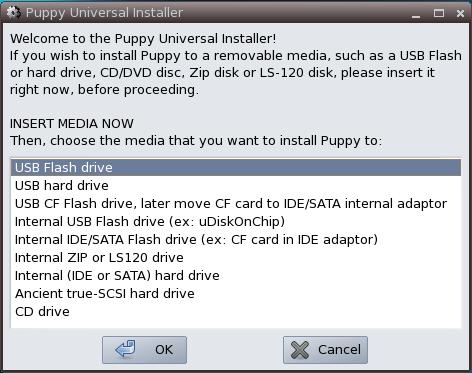

Puppy Linux includes a USB drive installer that's very easy to use, but it knows how to install only the version that is running. That's why you needed to make a CD of your distro earlier. Boot that CD and plug in a USB drive. Click on install on the desktop. Choose Universal Installer from the first page.

Figure 13. Puppy Universal Installer

Click OK twice. The dialog is self-explanatory, with options to correct things should a problem arise, and plenty of confirmation before actually writing to the USB drive.

Congratulations, you've just created your own Linux distribution, which you can hang on your keyring and boot on just about any PC you find. As long as the PC has at least 256MB and can boot from USB, you can boot your Linux desktop, do your work and not affect the underlying system.

So, there are several ways to get Linux on your keyring:

Use the USB drive version of a major distro.

Use a smaller, compatible distro, like Puppy Linux.

Create your own unique distro using Woof.

With that many options, you can trade-off customization against effort to get exactly the right solution for your needs.