Web site vulnerabilities often occur in very non-obvious ways. Whether you're a Web developer or run a Web site, you need to understand how it's done and how to test your site.

Almost every week the media picks up on another case of sensitive data being retrieved from Web sites with bad security. Web application security never has been more important, yet many Web sites never have been audited for security in a meaningful way. Although careful application architecture can help minimize security risks in code, a complete approach to Web application security considers the entire life cycle of the application, from development to deployment. In order to test whether your Web site is truly secure, consider using the same tools attackers do.

Penetration testing is the art of assessing the security of a system by simulating an attack or series of attacks. The goal of the penetration test is not necessarily to exploit the system if a flaw is found, but to audit potential attack vectors stringently and provide data that can be used to evaluate the potential risk of an exploit, and to find a solution to secure the system.

The Samurai Web Testing Framework is a security-oriented distribution that focuses on penetration testing for Web applications. It includes a variety of graphical, command-line and browser-based tools to test for common Web vulnerabilities. It's available as a live CD image from samurai.inguardians.com.

In this article, I look at using Samurai to test for a couple of the top Web application security risks as defined by the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP). This is not specifically a list of attack vectors. Technically, many of the risks listed below are exploited using various forms of SQL injection. Rather, this list was developed by OWASP combining “threat agents, attack vectors, weaknesses, technical impacts and business impacts...to produce risks”. OWASP's top ten risks (www.owasp.org/index.php/Top_10):

Injection flaws.

Cross-site scripting.

Broken authentication and session management.

Insecure direct object references.

Cross-site request forgery.

Security misconfiguration.

Insecure cryptographic storage.

Failure to restrict URL access.

Insufficient transport layer protection.

Unvalidated redirects and forwards.

In the interests of keeping the scope of this article manageable, I focus on injection flaws and cross-site scripting.

Disclaimer: please do not try any of these examples on production Web sites. Linux Journal recommends that you set up a virtual environment with a copy of your Web site to test for vulnerabilities. Do not test over the Internet. Never use any of these examples on a Web site that is not yours. Linux Journal is not responsible for any damage to data or outages to services that may arise from following any of these examples.

Injection flaws occur when the application passes user input to an interpreter without checking it for possible malicious effects. Injection flaws can include operating system command injection, LDAP injection and injection of many other interpreters called by a Web application using dynamic queries. One of the most common injection vectors is SQL injection. Depending on the specific vulnerability, attackers could read passwords or credit-card numbers, insert data into the database that gives them access to the application or maliciously tamper with or delete data. In extreme cases, operating system files could be read or arbitrary system commands could be executed—meaning game over for the Web server.

Login forms are primary targets for SQL injection, as a successful exploit will give attackers access to the application. To start testing an application for SQL injection vulnerabilities, let's use some characters that have special meaning in SQL to try to generate an SQL error. The simplest test, using a single quote (') as the user name, failed to generate an error, so let's try a double quote followed by a single quote ("'):

SQL Error: You have an error in your SQL syntax; check the manual

that corresponds to your MySQL server version for the

right syntax to use near '"''' at line 1

SQL Statement: SELECT * FROM accounts

WHERE username='"'' AND password='"''

Not only is this form vulnerable to SQL injection, but also the error message has thrown up the exact SQL statement being used. This is all the information you need to break into this application, by using the following text in both the user name and password fields:

' or 1=1 --

This changes the original query to one that can match either the correct user name and password, or to test if 1=1. Because 1=1 will evaluate to true, the application accepts this as your login credentials and authenticates you. Even worse, assuming you're not attackers, once you're logged in, you now can see that you're the admin user. This is because the SQL query will look at each row, one by one, to see on which row the query returns true. Because you've tampered with it always to return true, MySQL will return the first row. Because the first user created is quite often the administrator or root user (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The first row of the users table often contains the administrator user.

Not all applications are going to prove so easy to break into—particularly those that do not divulge as much information about the database and table structure in the error message. An auditing tool will let you iterate over a range of possible strings quickly. w3af, the Web Application Attack and Audit Framework, has a range of plugins to assist in scanning for and exploiting vulnerabilities, including SQL injection.

Launch the w3af GUI from the Applications→Samurai→Discovery menu. Enter the Web site URL you'd like to test in the Target: field, and then expand the options under discovery in the plugin box. Scroll down until you find the webSpider plugin, and check its box to enable it. In the pane to the right, the options for the webSpider plugin will be shown. Tick onlyForward, and select Save Configuration. Now, scroll back to the top of the plugins box, and expand Audit. Scroll down to sqli and check its box to enable it.

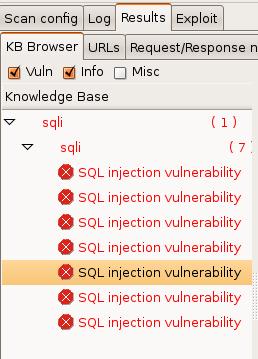

Once the scan is completed, you can look at the Results tab and see that w3af found seven separate places within the application that could be exploited by SQL injection (Figure 2).

Figure 2. w3af Results Tab, Showing Discovered Vulnerabilities

Another tool included with Samurai that can discover SQL injection vulnerabilities is Grendel-Scan. Launch Grendel-Scan from the Applications→Samurai→Discovery menu. Under Base URLs, insert the URL of the Web application you would like to test and click Add. Untick Enable Internal Proxy. Let's use Grendel's Web spidering module instead. Under Scan Output, select a directory for Grendel-Scan to store its output report. This directory must not exist. The application will expect to create it. Select Start Scan from the Scan menu to start.

The scan will take some minutes to complete, depending on the size of the Web application. Once finished, navigate to the designated output directory to view the report. Here, report.html tells you that among other issues, a possible SQL injection vulnerability was found (Figure 3). The clean output of Grendel-Scan makes it a great tool to send attractive and easy-to-read vulnerability reports to upper management as part of a reporting requirement.

Cross-site scripting can occur when the application accepts user input and sends it back to the browser without validating it for malicious code. There are two types of XSS attacks: reflected and stored. A stored attack injects code into the page that is persistent and will be activated by the victim's browser when requesting the page. A common example of a stored cross-site scripting attack would be a script that is injected through a comment field, forum post or guestbook. If the application doesn't guard against potentially malicious input data and allows the script to be stored, the browser of the next person to load the page will execute the malicious code.

By contrast, a reflected or nonpersistent cross-site scripting attack requires the victim to click on a link from another source. Here, instead of being stored in the Web application's database, the malicious script is encoded in the URL. XSS exploits can allow attackers to deface a Web site, redirect legitimate traffic to their own site or a site of their choice, and even steal session data through cookies.

This first test utilizes a formidable tool that enjoys wide popularity among attackers—a Web browser. Although automated tools can take the pain out of iterating over a long list of tests, the simplest method to start testing your site for XSS vulnerabilities is by using a browser. You'll need to find a page on the application you'd like to test that accepts user input and then displays it—something like a guestbook, comment field or even a search dialog that displays the search string as part of the results.

The canonical check for an XSS vulnerability is considered to be the snippet of code below:

<script>alert('xss!')</script>

If the Web site isn't properly filtering input, this script will execute in the browser and then display a pop-up message with the text “xss”. There's some bad news for my little Web application here. It's so vulnerable that this simplest of strings was able to exploit it (Figure 4).

Usually, at least some form of input filtering is employed, and this string won't get through intact. By examining the source of the generated page, you can try to diagnose what characters are being filtered to craft more sophisticated strings. If you inject the same string into a slightly more secure Web form, you can see by the result that the script tags are being stripped out and the single quotes are escaped:

Name: Me! Message: alert(\'XSS!\')

You could continue encoding different parts of the string and observing the results to try to get past the filter. Or, to speed up the process, you could use an automated tool. Samurai includes the XSS Me plugin for Firefox by Security Compass. Navigate to the page you'd like to test, then select XSS Me→Open XSS Me Sidebar from the Tools menu. Select Test all forms with top attacks from the sidebar. For the curious, the strings that the XSS Me uses can be viewed in Tools→XSS Me→Options→XSS Strings, and more strings can be added.

Figure 5 shows that XSS Me has discovered that this application is vulnerable to DOM-based XSS attacks. This is a particularly insidious way of exploiting an application, as it doesn't rely on the application embedding the malicious code in the HTML output.

Another tool that can scan for XSS vulnerabilities in Samurai is, again, w3af. This powerhouse tool is capable of scanning for and exploiting almost any vulnerability you care to name. Here, let's configure it to scan the Web application for XSS vulnerabilities.

Launch the w3af GUI from the Applications→Samurai→Discovery menu. Enter the Web site URL you'd like to test in the Target: field, and then expand the options under discovery in the plugin box. Scroll down until you find the webSpider plugin and check its box to enable it. In the pane to the right, the options for the webSpider plugin will be shown. Tick onlyForward and select Save Configuration. Now, scroll back to the top of the plugins box, and expand Audit. Scroll down to xss, and check its box to enable it (Figure 6).

Click Start to start the audit process. Depending on the size of the Web application, this could take a few minutes as the spider plugin discovers every URL, and then the audit plugin tests all applicable forms for XSS vulnerabilities. Once complete, navigate to the Results tab, which will itemize the vulnerabilities found.

Although useful, penetration testing is only part of the picture. To truly address these risks, applications must be designed, implemented and deployed with security in mind. Code analysis tools are helpful in locating places where application code deals with user inputs, so the code can be audited for input validation, strong output encoding and safe quote handling. Careful deployment using the principle of least privilege and employing chroot jails can help minimize the damage attackers can do if they gain access to your application. Never allow your database or Web server process to run as the root user.

Hopefully, this article can serve as a jumping off point to help you approach Web application security from a more active point of view, but there are many exploits and aspects of these two specific exploits that aren't covered here. For further reading, see the OWASP Wiki at www.owasp.org.

Special thanks to Adrian Crenshaw from irongeek.com, the author of our example application, Mutillidae. Mutillidae is a Web application designed to be deliberately vulnerable to the OWASP top ten in an easy-to-understand form for education purposes. Check out his site for some excellent resources on Web application security.