People unfamiliar with Rockbox often make the assumption that because it's an open-source project providing an operating system (or firmware) for digital audio players, it must be based on GNU/Linux. In this article, I set the record straight and tell you what Rockbox really is, and why you might be interested in it.

Let me start by disabusing you of the notion that Rockbox is Linux of some flavor, or that it started out that way. It's not. You are, of course, reading Linux Journal, so you could be forgiven for thinking it is, but I just want to make sure you are aware right from the get-go that it isn't. With that small formality out of the way, let me get on to what it actually is, which is a replacement firmware for a growing number of digital audio players.

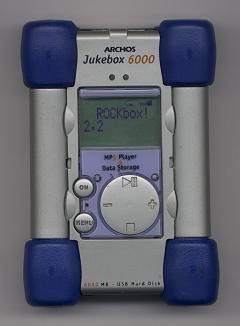

Back in 2001 or so, Rockbox started life as a replacement firmware for just one digital audio player (DAP), which was the Archos Jukebox (sometimes referred to as the Archos Player, Figure 1). A few owners of this very early device were left feeling dissatisfied with the buggy firmware that came with the device, and also felt it was lacking some important features. Those folks decided they could do better, and so Rockbox was born. That original device was very limited in what it could be made to do when compared with modern DAPs. It featured a very slow 11MHz CPU and, therefore, had to include a dedicated chip for decoding MP3 audio. This meant that in the early days of Rockbox, the only music format it could play was limited to MP3 or uncompressed PCM Audio (WAV). These days, that list has expanded greatly, and the firmware now plays some 27 formats. Those of us associated with the project are fairly confident (not to say a little smug) that this is way more than any other firmware made by anyone, be it open or closed, anywhere in the world.

Figure 1. Original Archos Player (Photographer: Björn Stenbeg)

Of course, in addition to now supporting this rather large and, in not a few cases, esoteric list of formats, Rockbox runs on a vastly larger variety of players these days too. The list of supported DAPs has grown steadily over the years, with the iRiver H100 series being the first software codec target that was added sometime in 2004, and from there growing to include other players made by Apple, Archos, Cowon, iRiver, Logick, Meizu, MPIO, Olympus, Onda, Packard Bell, Philips, Samsung, SanDisk, Tatung and Toshiba. Among these players, the architectures on which Rockbox has to run necessarily has been extended too, from the original SH1 in the Archos player, to ColdFire, ARM and even MIPS hardware.

Porting Rockbox to new players is a time-consuming business, and doing so varies from just plain hard to nearly impossible. Where a player falls in this scale of difficulty depends on a number of factors, but the main influences tend to be how easy the manufacturer has made it to get custom code running on the device and how much documentation exists for the underlying hardware. On a great many of the players on which Rockbox runs, reverse engineering of the hardware has been done purely by Rockbox hackers; however, a large hat tip in the direction of the iPodLinux (IPL) Project is due, without whose extensive reverse engineering of the early range of iPods running on PortalPlayer hardware, the current Rockbox port to those players probably would not have been possible.

The PortalPlayer platform is notorious among embedded hackers as having no publicly available documentation, so each and every piece of functionality on those devices using it has had to be painstakingly worked out, and the IPL hackers spent a great deal of time doing this. Coming back to the first point, about how easy it is to run custom code at all, the more recent iPods (since the second generation of the iPod Nano, in fact) have raised the bar still higher, because the device requires the code it executes to be both signed and encrypted in hardware before it will run. Back when Apple launched this device, hope was very low in the Rockbox community that it ever would be possible to get a port running on it. However, a flaw in the original firmware turned up last year that allowed some very talented folks to get code running, and now there's a port of Rockbox running on that device too. Other platforms have proved somewhat easier—for instance, the Toshiba Gigabeat F had hardware for which documentation was relatively simple to come by.

Rockbox's driving philosophy always has been to provide the best portable music player experience that it can. As mentioned previously, 27 codecs is just part of that. Although it allows end users to navigate their music collection via a database based on the music's metadata content these days, it originally started with just a file browser—a feature that remains a firm favorite with the core of the Rockbox Project team. Every action to play back music requires a playlist, as this is how Rockbox works. Creation of playlists can be done on the fly where the end user isn't even aware it has happened. Or, they can be constructed manually either within Rockbox itself or in the user's favorite music management program, assuming it can generate standard M3U format files.

Another key feature the firmware offers is bookmarking—invaluable for those who listen to audio books and need to keep track of where they are within the file when they shut down their players. Rockbox allows users to keep many such bookmarks, letting them skip around between multiple files with ease.

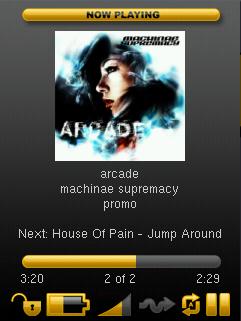

One of the oldest features in Rockbox, which has only improved over time, is the customizable While Playing Screen (WPS). In the very early text-only versions of Rockbox, this allowed users to choose what information about the currently playing tune they wanted displayed. In the most recent versions of Rockbox, this now allows users to decide where, or indeed if, they want Album Art displayed, along with all the various pieces of metadata, or have a colorful backdrop and pretty much anything they want (Figure 2).

Another favorite feature, particularly with Rockbox users who are sight-impaired, is the implementation of a voice feedback system. Once this is turned on, all menus within the Rockbox interface announce themselves to the user, so the entire interface can be navigated without needing to see the screen. In its default state, this also allows the player to spell out filenames, so users can navigate their music collection. This can be enhanced further with the use of speex format .talk files, which are pre-generated with a PC-based tool and allow the player actually to speak the names of files and directories.

A somewhat more recent feature, added in the last couple years, has brought movie playback to a large quantity of supported Rockbox players. Once you have transcoded your movie of choice and resized it to fit on the device's screen, you can watch MPEG1 and MPEG2 movies at your leisure, all made possible by Rockbox's rich plugin API.

The features I've highlighted here barely scratch the surface of what is possible with Rockbox, and if you are at all interested in discovering more, check out the rather comprehensive manual available on the Rockbox home page (www.rockbox.org). The project couldn't possibly provide all the features it does without standing on the shoulders of a number of other open-source giants. A great deal of the codecs that Rockbox uses are derived from other open-source codebases. The folks that provide that code have helped by providing countless hours of their own work that Rockbox has built on. Libmad, ffmpeg, flac, vorbis, speex, wavpack, libmpeg2 and libmtp are just a few of the other teams that all deserve the heartfelt gratitude of the current Rockbox user base, because without them, virtually all of their favorite music wouldn't play back as well on the Rockbox platform.

Figure 2. The While Playing Screen Used by Rockbox's Default Theme

Rockbox has been fortunate enough to have been accepted to the Google Summer of Code program during the last few years, and this year is no exception. Perhaps one of the most interesting projects that is being kindly funded by Google's deep pockets is that of “Rockbox as an Application” or RaaA.

Increasingly, consumer electronics devices that are capable of music playback are shipping with very capable operating systems already, and it makes little sense to replace an entire operating system just to get superior music playback on such a device. Because there has been code in the Rockbox repository for a long time to build a “Rockbox Simulator”, which runs on a PC using SDL, an opportunity to turn this into a real application that could execute on Android, Symbian, Maemo or even Windows Mobile (god forbid!) already existed, and now is being put into action. The aim of this project is to separate the playback engine from the firmware portion of the code, allowing you to install Rockbox on your phone without sacrificing its ability to make phone calls or surf the Web. It's thought that this is a better idea than trying to add a network stack and all the other goodies you'd need to make Rockbox a convincing alternative OS on your mobile phone. In actual fact, someone forked Rockbox's simulator a few years ago to the Motorola RockR series of phones in just this way, but sadly, the folks responsible for this port never gave the project any decent code back, and that particular set of targets remains unsupported in the trunk of the Rockbox codebase.

The majority of Rockbox's codebase is written in C, but there's a smattering of routines written in assembly code where it makes sense to squeeze the absolute last ounce of performance out of the player. Most of those routines are in the codecs, where every clock cycle counts, especially with some of the heavyweight formats like Monkey's Audio, which even the most powerful Rockbox players struggle with at maximum compression.

The Rockbox kernel has been written from the ground up, and among its features there are two things that probably will stand out as substantially different to people who are familiar with other modern OS kernels. First, because the vast majority of Rockbox-capable DAPs do not possess an MMU, Rockbox's kernel does not feature any method of dynamic memory allocation. This has been a contentious issue in the Rockbox community for a long time now, and new developers constantly bring it up. The lack of MMU is, of course, not a complete showstopper. It's perfectly possible to come up with a malloc implementation that does not require an MMU, and this is often the point they make. The reason the project has resisted it historically, and continues to do so to this day, is that any implementation requires a pool of free memory from which to allocate. The Rockbox old guard all argue that this is a waste of precious resources on the often extremely memory-constrained platforms on which Rockbox executes, and that every piece of available memory should be used to buffer as much music as possible. This means people coming to programming for Rockbox for the first time have to get used to thinking about statically allocating all the memory they need at compile time, a mode of programming foreign to most developers these days.

The second interesting feature in the Rockbox kernel is the threading model, which is cooperative rather than preemptive. This is mainly a historical artifact these days, and there has been repeated discussion about moving to a preemptive model, which so far has failed to reach a conclusion. In the meantime, this means, again, that anything designed to run on the Rockbox kernel has to have its execution thought about carefully and must consciously yield to other threads at opportune moments if it is to play nicely with the rest of the system.

As highlighted previously, Rockbox provides a rich plugin API that can be used via either compiled C code or in up-to-date versions via a growing library of LUA functions. A few support programs also go with Rockbox, not the least of which is the Rockbox Utility, a multiplatform installation tool. This is written in C++ using the Qt toolkit, and a version for all three major PC operating systems is maintained in statically linked form to make using it as easy as possible. There are some 92 people currently listed as having commit access to the central Subversion repository for Rockbox, with 40 of those active at the current moment. In addition to them, there is a sizable community of patch authors, artists and general helpers contributing to both the project's health and also to its vibrant and friendly atmosphere.

For those not skilled with a text editor and compiler, additions to and maintenance of the documentation are always welcome. Although it would be foolish to claim that the documentation is perfect, most of those involved in the project would say that as far as most open-source projects go, the documentation is pretty good. In addition to the manual and the wiki, which provide the static documentation for the project, there are numerous other ways for people to find and receive help. There are two active mailing lists, one aimed at the end user, which has proved to be perhaps the most popular support option for the community of blind users, and another where those who are interested in Rockbox development can exchange ideas. The Rockbox forums also are extremely active, and indeed, a lot of the Rockbox “staff” have made their entrance into the community by helping out others here. As with most other open-source projects, there is also an extremely active IRC channel on the Freenode network (www.freenode.net)—#rockbox is active for most of the day due to the community's diverse geographical (and some might say insomniacal!) nature. The channel is logged to make sure all discussions are searchable in case a developer misses something critical or otherwise interesting, and these logs are published on the project's Web site. Also, never let it be said that the Rockbox community is slow to adopt new technology. Recently @rockboxcommits has made its debut on Twitter for those who are keen to keep track of every change in the source code repository!