How to implement a Nagios-to-SMS service.

I'm a big fan of the Nagios network monitoring system and rely on it to tell me if something goes wrong with the systems for which I am responsible. I have made a large investment in time configuring Nagios to monitor exactly what I am interested in, and this effort would be wasted if Nagios detected a problem, but failed to communicate that problem to me. To make Nagios more robust, I wanted to make sure that its alerting mechanism did not depend on connections to the Internet—this would include the physical connection itself and internal and external services, such as e-mail, routing and DNS.

I have relied on e-mail-based systems in the past to deliver alerts; however, my dilemma was that if I was not getting e-mail, I did not know if this meant everything was okay or if there was some problem preventing me from getting the e-mail alerts, such as a down Internet connection or another kind of e-mail failure. I found that I became uneasy after long periods of silence and felt compelled to “poll” the system to make sure everything was okay.

On the other hand, I felt that if my alerting system was robust and I could trust it, my thinking would become “no news is good news”, and the absence of alerts would mean everything was fine.

I've found that the Short Message Service (SMS) text service available on GSM cellular networks meets my requirements for a trusted alerting server. It is generally available and is unlikely to go down. A major disaster certainly could take down or overwhelm the cellular service, but I figure I would be aware of such an event and probably would have bigger and more pressing concerns than network management at that point.

There are several different ways to implement a Nagios-to-SMS service, and I certainly have not explored them all. This article describes the system I am using, which is the MultiTech Systems MultiModem iSMS Intelligent SMS server (Figure 1) in combination with a public domain Perl script running on a Linux-based Nagios server.

I selected this hardware and software combination for the following reasons:

Another company had done all the required work to integrate the iSMS device with Nagios, clearly documented the process and made this freely available on the Web, including the Perl script described in this article.

A major feature of the Perl script is the ability to “ACK” or acknowledge a Nagios alert. This means you don't have to have any kind of IP connection to your Nagios server to perform acknowledgements. The ability to acknowledge alerts is helpful when you are off the IP network, as it stops any future alerts and can prevent the alerts from going to others if you have configured Nagios to do this. The script also can force a service or host back to an “OK” state if desired.

The iSMS device is a standalone “appliance” and does not depend on any infrastructure other than a (local) Ethernet connection, GSM cellular service and electrical power. Most other products in this area are similar to traditional analog modems in that they have serial connections hard-wired to a specific host. As the iSMS is connected via Ethernet, it can be accessed and shared by multiple hosts. The particular model I used has a single GSM modem, but four- or eight-modem versions are also available.

Other Nagios users are using conventional mobile phone handsets in this role, but I feel that consumer-level power supplies and some kind of jury-rigged mounting of a phone in a machine room would undermine the reliability I want. The iSMS has a robust metal case and can be attached securely to a rack. The power plug is threaded to the chassis to prevent accidental unplugging.

The iSMS has a Web-based administration interface and supports multiple methods of communication, including a “Telnet” interface to connect directly to the GSM modem for use of “AT” commands and multiple APIs. These include both TCP and HTTP APIs for sending and receiving SMS messages or querying the status of queued messages. Certainly, you could use Web-based or e-mail-based tools to create a similar alerting functionality, but SMS is somewhat unique in that it does not require an IP connection and is generally available wherever a modern cellular infrastructure exists.

As you can see in Figure 1, the iSMS is packaged in a sturdy metal enclosure. I used large plastic wire ties to mount the iSMS to a horizontal rack post, but it also can be mounted with screws. The antenna is visible on the top, and there is a little hatch on the bottom where the Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card is plugged in.

The product is generally available, and I simply used a price comparison site to find the cheapest one, as I didn't feel I needed support from the vendor. MultiTech made several changes to its product while I was in the midst of writing this article. These changes included renaming the product, updating the firmware version and lowering the price. The iSMS previously was named SMSFinder, and you will see this reflected in the name of the Perl script and in other places. The firmware update required some changes in the Perl code. The original product was priced around $700, but it's now available in the $400 range. This article describes the more recent version of the iSMS and Perl script.

I did not shop around between the different carriers for SMS service, as my company already had a corporate account with AT&T. I initially tried to walk into an AT&T retail store to buy service for the iSMS, but I was unable to purchase a service package that did not include voice. I ended up doing all the ordering and setup over the phone with AT&T corporate. I was able to get the SIM card at the retail store, which saved me from having to wait for the card to be mailed to my location. AT&T calls its text-only SMS service telemetry. It may make the ordering process easier if you use this terminology with your carrier.

Once you reach the correct ordering department, all you should need to do is read them two numbers: the first identifies the iSMS, and the second identifies the SIM card. The number for the iSMS is the International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) number printed on the iSMS chassis label. The second number, the Integrated Circuit Card ID (ICC-ID) is printed on the SIM card. Once I had communicated these numbers to the carrier, I was able to establish the service and send a test message within a few minutes. Make sure you make note of the subscriber number given to you, as this will be the source of SMS alerts and the destination for your “ACK” and “OK” responses. It is handy to associate a contact name with this number for caller-ID purposes on your mobile phone (for example, “Nagios”). With the service I purchased, the one-time setup fee was $18, and the monthly charge is about $9, depending on usage.

I wanted the iSMS and the Nagios server to be able to send messages for as long as possible if there were a problem with network connectivity or power. In my situation, this meant locating the iSMS, the Nagios server and their shared Ethernet switch all in the same computer room and plugged in to the same redundant UPS. Of course, I could eliminate the switch from this configuration by using an Ethernet crossover cable to link the iSMS and the Nagios server directly, but that would limit communication to the one server. It also would eliminate most of the advantages over the hard-wired GSM modems that I was trying to improve upon.

The Perl script can be found on the MonitoringExchange site (www.monitoringexchange.org) or the Nagios Wiki (www.nagioswiki.org). Searching for “smsfinder” should get you to the correct place. The documentation for the script includes installation instructions, example Nagios configuration files and screenshots of the iSMS Web user interface. The author used an interesting approach to create a single script that serves three different purposes. The script checks to see which filename was used to call the script and then performs a completely different function depending on which name was used. The script has three names:

smssend.pl: a Nagios “command” used to send messages about hosts and services via SMS.

smsack.cgi: a CGI script used by the iSMS to acknowledge alerts it has received via an SMS message sent by a mobile phone.

check_smsfinder.pl: a typical Nagios “plugin” or “check” script invoked by Nagios on a scheduled basis to monitor the health of the iSMS device itself.

I stored the actual script as /usr/local/nagios/smsack/smsack.cgi and made two symbolic links to it with the following names/paths:

/usr/local/nagios/smsack/sendsms.pl

/usr/local/nagios/libexec/check_smsfinder.pl

Apache will want to execute an actual file as a CGI, while Nagios will not care about the symbolic links. Figure 2 provides an overview of how the script interacts with the other components of the system.

The least complex use of the script is when it is called check_smsfinder.pl. Nagios runs this check script at scheduled intervals, and the script queries a status page on the iSMS via HTTP to make sure it is running okay. The script returns the exit status back to Nagios. The performance data includes the signal level for the GSM modem, the model number and the firmware version.

The next use of the script is when it is called as sendsms.pl by Nagios. In this form, it is used to send host and service alerts and acknowledgements to the iSMS for delivery to mobile users. The script uses the “HTTP Send API” to request that it transmit the SMS message. The iSMS queues the request and returns a message ID. The end user can query the iSMS with the message ID to find out if the SMS message was sent successfully or failed for some reason. When invoked as sendsms.pl, the script has a --noma option, which will query the iSMS after queuing the message to get its status. This takes slightly longer to execute, as the script has to wait for confirmation that the message actually was sent (or failed). The documentation refers to “NoMa” but does not explain why the option was named that way.

The most complicated use of the script is when it runs as the smsack.cgi CGI script under Apache. The recipient of an SMS alert can send the entire message back to the iSMS with the string “ACK” or “OK” prepended to the message text. When this SMS message is received by the iSMS, it uses the “HTTP Receive API” to call the smsack.cgi CGI script with the ACK message. The smsack.cgi CGI script parses the message text, determines whether it is a host or service being acknowledged, verifies that the sender's phone number is in the Nagios object cache and then uses the Nagios “external command” interface to signal Nagios. Nagios then tries to match the host or service name with one it knows about, and if this match is successful, it acknowledges the problem. The script also creates a note on the host or service page indicating that the problem was acknowledged by the sender's mobile number.

The acknowledge feature expects the entire SMS alert message to be sent back to the iSMS with the “ACK” text prepended. I found the best way to do this on both older text-based and newer graphical mobile phones was to “forward” the entire message received from Nagios back to the Nagios phone number and then insert the ACK text at the beginning of the message.

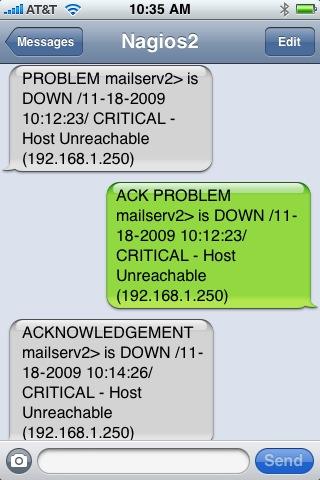

Figure 3. Apple iPhone Screenshot

Figure 3 shows a screenshot from an Apple iPhone. The initial “PROBLEM” alert received from the iSMS is at the top (shown in gray). The message forwarded back to the iSMS with the prepended “ACK” is in the middle (shown in green), and the receipt of the acknowledgment sent from the iSMS is at the bottom (shown in gray). This entire transaction can be accomplished in less than a minute.

I was able to get everything running in a day or two, but I did have to resolve several issues as part of the installation. I also discovered several problems that required changes to the Perl script. Therefore, it's important to test the scripts.

You can run the check_smsfinder.pl and sendsms.pl scripts on the command line to view their output directly. For example:

% /usr/local/nagios/libexec/check_smsfinder.pl \

-H 192.168.1.50 -u nagios -p secret

OK: GSM signal strength is 100.0% - \

model: SF100-G - \

firmware: 1.31|loginID=1607132337 strength=100.0%;40;20;;

% /usr/local/nagios/smsack/sendsms.pl \

--noma -H 192.168.1.50 -u nagios -p secret \

-n 14155551212 -m 'this is a SMS from nagios'

"this%20is%20a%20SMS%20from%20nagios" to 14155551212 \

via 192.168.1.50 send successfully. MessageID: 37

The smsack.cgi script is a little harder to debug than the command-line scripts, but the usual Apache log files access_log and error_log are useful in that they will contain the HTTP response codes when the CGI is invoked by the iSMS. You also can use the method described below under “Network Capture” to look for problems with the CGI script.

In many places within Nagios, the Perl script and the iSMS device contain debugging information. Knowing where those are will help you with your installation.

The iSMS can send helpful debugging messages to a remote host via syslog. The Nagios server would be an ideal destination for the messages, as all logging can be consolidated in once place. The remote syslog host is specified in the iSMS Web GUI. The iSMS syslog messages use the LOG_LOCAL0 facility. I added a local0.* /var/log/isms entry to my /etc/syslog.conf file to capture all messages. The log file will record all SMS messages sent and received by the iSMS, for example:

Nov 23 09:27:59 smsgw MultiModemiSMS modem: sentlog:

[SENT TO] : 14155551212 : [MSG] : this is a SMS from Nagios

The log also contains any authentication failures. This is useful because the check_smsfinder.pl and sendsms.pl scripts authenticate themselves to the iSMS every time they run.

The iSMS has a concept of an “Inbox” for SMS messages received from mobile users and an “Outbox” for SMS messages being sent out from the iSMS. You can examine these boxes via the iSMS Web interface to find out whether a message actually was received or transmitted.

Nagios logs to the file nagios.log, which is typically found in the /usr/local/nagios/var directory. You can use this log to verify that Nagios is generating an alert for a problem and that a command has been used to send an SMS (notify-host-by-sms):

[1258664139] HOST NOTIFICATION:

epearce-sms;mailserv2;DOWN;notify-host-by-sms;CRITICAL -

Host Unreachable (192.168.1.250)

The Nagios log also will show the results of smsack.cgi running after getting the “ACK” back from a mobile user:

[1258500602] EXTERNAL COMMAND:

ACKNOWLEDGE_HOST_PROBLEM;mailserv2;1;1;1;14155551212;

Acknowledged by 14155551212 at 09/11/17 15:29:57

ACK PROBLEM mailserv2> is DOWN /11-17-2009 15:28:21/ CRITICAL -

Host Unreachable(192.168.1.250)

The smsfinder scripts log to smsfinder.log (also in the Nagios var directory). This file will contain debugging information for the sendsms.pl and smsack.cgi uses of the script. The lines containing “SMSsend” show the status of sendsms.pl when it is being run by Nagios. For example:

2009/11/19 12:55:39 SMSsend:

"PROBLEM...mailserv...is...DOWN...CRITICAL..."

to 14155551212 via 192.168.1.250 queued successfully.

MessageID: 14

Lines containing “SMSreceived” and “SMSverify” will show the progress in parsing any acknowledgement SMS messages received by the smsack.cgi script:

2009/11/12 09:15:41 SMSreceived:

username=nagios&password=secret&XMLDATA=

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="ISO-8859-1"?>

<Message Notification>

<SenderNumber>14155551212</SenderNumber>

<Message>

ACK PROBLEM HostAlert mailserv2 192.168.1.250

/AllServices is DOWN

/11-12-2009 09:11:46/ CRITICAL -

Host Unreachable (192.168.1.250)

</Message>

<Date>09/11/12</Date>

<Time>09:15:36</Time>

</Message Notification>

2009/11/12 09:15:41 SMSverify

status = ACKed - ACCEPTED:

From=14155551212 Received=09/11/12 09:15:36

Status=ACK Host=mailserv2 Service=AllServices

MSG="ACK PROBLEM ... Host Unreachable (192.168.1.250)"

I initially had multiple overlapping “Directory” statements in the Nagios section of the Apache configuration file. The net effect was a “Permission denied” when the CGI was being run. I figured this out by using the method described below and by looking at the Apache access_log and error_log files.

If you think there is some communication problem with the script, you can monitor the traffic between Nagios, Apache and the iSMS by listening on the network. I used tcpdump to capture the HTTP traffic and see error messages:

% tcpdump -v -s 0 -w /tmp/cap host 192.168.1.50

In this example, I used the -v option for verbose output, the -s 0 option to capture as much of the packet as possible and the -w option to write the captured traffic to the /tmp/cap file. The “host” keyword indicates that I want all traffic to and from the IP address of the iSMS (192.168.1.50). I ran this command on the machine hosting both Nagios and Apache, so it should see all communication between these services and the iSMS. I then generated some SMS messages traffic by causing Nagios to send out a “PROBLEM” message, which I then acknowledged via my mobile phone. You should see the number following “Got” incrementing as packets are being captured:

tcpdump: listening on eth0, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet),

capture size 65535 bytes

Got 22

I then interrupted the capture and converted the captured data to plain text:

% tcpdump -A -r /tmp/cap > /tmp/txt

The -A option writes out ASCII text, and the -r option reads capture data from a file. Examining the /tmp/txt file allows you to see the entire HTTP transaction between Nagios, the iSMS and the CGI script:

12:50:09.434851 IP nagios.46058 > smsgw.http:

P 1:266(265) ack 1 win 46

<nop,nop,timestamp 2801435752 1987587011>

GET /sendmsg?user=nagios&passwd=secret...text=ACKNOWLEDGEMENT...

12:50:09.501524 IP smsgw.http > nagios.46058:

P 1:29(28) ack 266 win 6432

<nop,nop,timestamp 1987587017 2801435752>

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

ID: 2078

In this capture, you can see that the sendsms.pl script invoked by Nagios (hostname nagios) has sent an HTTP GET to the iSMS (hostname smsgw) containing the Nagios “ACKNOWLEDGEMENT” message. The “ID: 2078” response from the iSMS back to Nagios indicates that the message has been queued for sending and that the ID for this SMS message is 2078. You also might note that the user name and password for the iSMS “nagios” account is being sent in the clear—not perfect, but I think this is a pretty low security risk, as this transaction is internal to the company network.

My original iSMS came with version 1.20 firmware. This worked fine with the original Perl script, but it had a problem in that it was somewhat “single user”. For example, if you happened to be logged in to the iSMS Web user interface while the check_smsfinder.pl script ran, it would return a bad status, and Nagios would create an alert for the device. Upgrading to the newer firmware fixed this problem, but broke the check_smsfinder.pl script. The Perl script has been updated, but the version of the script now is tied to the firmware version running on the iSMS.

Because this is a Perl script, it can be modified easily. If you do not like the format of the message being sent out by Nagios, you can change this in the Nagios “command” definition—for example, “notify-host-by-sms” and also change the Perl script to parse whatever format of a message you want to send back from your phone. The script authors have changed their message format over time to make it easier to parse, as problems were discovered with whitespace in service names and host alerts that would change format depending on whether the host definition contained an IP address (such as in the case of DHCP clients).

I am very pleased with how this alerting service has worked out. The iSMS has been solid since the moment I installed it, and the associated script has worked perfectly once I tweaked my Nagios setup to match it. I have high confidence that I will get alerts regardless of the nature of the problem.

Thanks to Birger Schmidt and his colleagues from NETWAYS GmbH (www.netways.de) for writing the original script, updating it and taking the time to review this article, and to Chris Reilley (www.reilleydesign.com) for Figure 2.