The git and quilt tools were developed by Linus Torvalds and Andrew Morton for the same reason—to help organize patches. But part of Andrew's motivation in developing quilt was to avoid having to adapt his work habits to git. So, what do you get if you cross those two tools together? Apparently, you get StGit (stacked git), a Python script developed by Catalin Marinas and various others. It emulates quilt's ability to push and pop patches onto and off of a stack, but it does so on top of a full git repository. Thus, users can take advantage of the full range of git features, in addition to the pushing and popping features of quilt.

Large numbers of occurrences of the big kernel lock (BKL) are being expunged from the kernel. This isn't exactly news, but the pace of BKL patches seems to have stepped up lately. The basic pattern seems to be to push the BKL out of the core code and into specific drivers. This way, only a single piece of code relies on a given occurrence of the BKL. This lets the developers replace just that occurrence with something that does a different kind of locking that works for just that bit of code. The whole problem with eradicating the BKL is that the true locking requirements of anything that uses it are really very different from each other. So, if a lot of stuff depends on a single instance of the BKL, it's just impossible to recode that instance of the BKL to be less heavy-handed and still work for everyone. That's one reason why various folks used to say getting rid of the BKL would be nearly impossible. But lately, thanks to this whole process, folks like Thomas Gleixner and Jan Blunk and others are ripping the BKL out of the kernel in big fistfuls.

On systems with tons of CPUs, just listing the boot messages on the screen can cause big delays in the boot process and produce so much output, any information that actually might be useful for debugging is simply buried under tons of other data. Mike Travis calculated that with 4,096 processors and a console baud rate of 56K, the boot messages would take almost an hour and a half just to display. He's posted some patches and worked with various folks like Andi Kleen and Ingo Molnar to help reduce the number of less-relevant messages that come through during startup.

Relicensing kernel code is tricky. You need to get permission from everyone who's submitted patches, because those people hold the copyright on their own contributions and have (modulo some legal fuzziness) released their code under the same license as the rest of the code, or under the licensing that they specify when they submit the patch. So, when Mathieu Desnoyers wanted to dual-license portions of the tracepoint code under the GPL and the LPGL, and other portions under the GPL and BSD licenses, he had to ask all the contributors for permission.

In the old days, that would be a nonstarter, because identifying all contributors would involve combing through mailing-list logs and Usenet logs, and even then, there wouldn't be any guarantee that everyone had been found. With the advent revision control for the kernel and the Signed-Off-By headers that are now standard with all patch submissions, it's now trivial to list everyone who's contributed to a piece of the kernel, as far back as the revision control records go.

Even so, actually getting everyone's permission is not always a done deal. In this case, Ingo Molnar rejected Mathieu's request, putting Mathieu in the position of either having to abandon the project, persuade Ingo to change his mind or extract Ingo's code and relicense the remainder, which would be very difficult. It's unclear how this particular case will turn out, but it's at least possible the relicensing will take place.

You often may need to compare one version of a file to an earlier one or check one file against a reference file. Linux provides several tools for doing this, depending on how deep a comparison you need to make.

The most common task involves comparing two text files. The tool of choice for this task is diff. With diff, you can compare two files line by line. By default, diff notices any differences between the two text files, no matter how small. This could be as simple as a space character being changed into a tab character from one file to the next. The file will look the same to a user, but diff will find that difference. The real power of diff comes from the options available to ignore certain kinds of differences between files. In the above example, you could ignore that change from a space character to a tab character by using the -b or --ignore-space-change options, which tell diff to ignore any differences in the amount of whitespace from one file to the next.

What about blank lines? The -B or --ignore-blank-lines options tell diff to ignore any changes in the number of blank lines from one file to the next. In this way, diff effectively looks only at the actual characters when comparing the files, narrowing diff's focus to the actual content.

What if that's not good enough for your situation? You may need to compare files where one was entered with Caps Lock turned on for some reason, or maybe the terminal being used was misconfigured. You may not want diff to report simple differences in case as “real” differences. In this situation, use the -i or --ignore-case options.

What if you're working with files from a Windows box? Everyone who works on both Linux and Windows has run into the issue with line endings on text files. Linux expects only a single newline character, while Windows uses a carriage return and a newline character. diff can ignore this with the --strip-trailing-cr option.

diff's output can take a few different formats. The default contains the line that is different, along with a number of lines right before and after the line in question. These extra lines are called context and can be set with the “-c”, “-C” or “--context=” options and the number of lines to use for context. This default output can be used by the patch program to change one file into the other. In this way, you can create source code patches to upgrade code from one version to the next. diff also can output differences between files that can be used by ed as a script with the -e or --ed options. diff also will output an RCS-format diff with the option -n or --rcs. Another option is to print out the differences in two columns, side by side, with the -y or --side-by-side options.

The diff utility compares only two files. What if you need to compare three files? diff3 comes to the rescue. This utility compares three files and prints out the diff statements. Again, you can use the -e option to print out a script suitable for the ed editor.

What if you simply want to see two files and how they differ? Another utility might be just what you are looking for, comm. With no other options, comm takes two files and prints out three columns. The first column contains lines unique to the first file, the second column contains lines unique to the second file, and the third column contains lines common to both files. You can suppress each of these columns selectively with the options -1, -2 and -3. They suppress columns 1, 2 or 3, respectively.

Although this works great for text files, what if you need to compare two binary files? You need some way to compare each and every byte in each file. Use the cmp utility, which does a byte-by-byte comparison of two files. The default output is a printout of which byte and line contains the difference. If you want to see what the byte values are, use the -b option. The -l option gives even more detail, printing out the byte count and the byte value from the two files.

With these utilities, you can start to get a better handle on how your files are changing. Here's hoping you keep control of your files!

One of the biggest arguments used against Linux in grade-school-level education is that we aren't teaching kids to use the applications they'll need in the “real world”. As the Technology Director for a K–12 school district, I've heard that argument many times. After all these years, I still don't buy it. Truthfully, to give kids a well-rounded education, we should expose them to as many different types of technology as we can. Children should be comfortable using whatever tool is at their disposal to accomplish a given task. This isn't a new concept by any stretch of the imagination. For some reason, when it comes to computers, however, the “Microsoft Mantra” is all too prevalent.

Think about some other subject areas:

Language: teachers begin teaching grammar to young kids. They start with the simple concepts, like differentiating between nouns and verbs, and move on to tougher things. By the time students are finished in high school, they've likely been given many different types of writing assignments. The concepts they've learned allow them to write well as they continue in life. Guess what though? I never once was taught to blog in school. It just didn't exist. Thankfully, because I was taught the concepts of writing and grammar, I'm able to pull off the crazy world of blogging as if I were specifically trained for it.

Mathematics: just like with language, mathematics are taught with fundamentals. Specific problems are assigned (remember story problems?), but it's very clear that everything we learned in school was meant to be extrapolated upon.

Reading: I didn't go to the most prestigious school in the country. Heck, I didn't even go to the best school in the area. I am very certain, however, that no school assigns every book ever written to their students. Even if they did, more books are published every day. Again, it's the concept of reading that we learn, not specific books.

Driver's Ed: my first car was a 1978 Volkswagen Diesel Rabbit. It was a four-speed manual transmission, and it had the touchiest clutch I've ever driven. In driver's ed, however, I drove a cute little Dodge with an automatic. Sure, when I finally got a car, I had to learn a few new things, but my driver's education and driver's license prepared me perfectly fine. The rules, procedures and, yes, concepts were all the same.

So why are computers different?

I think there are a few valid arguments for specific applications being taught in schools. For vocational programs, especially if they are computer-related, a firm grasp of the specific applications that will be used is slightly advantageous. Even with that, however, it's important to teach concepts, because programs change all the time.

Higher-level education (college and so on) is certainly the time to begin specializing in specific areas. Some of those areas require certain applications and/or operating systems. Accountants, for example, might be expected to know how to use QuickBooks. Graphic designers probably would be expected to know Adobe Photoshop inside and out.

At the grade-school level though, we need to teach children not only how to use technology, but also how to learn to use technology. If we can offer students the use of Windows, Linux and Macintosh, and teach them Web 2.0, handheld computing and application concepts, we prepare them to succeed. Isn't that what we ultimately want for kids? For them to succeed in whatever they do?

Linux is the perfect tool for education. It plays well with other operating systems, and it offers such a wide variety of applications that it's silly not to expose children to its usage. Oh, and there's also that little thing called cost. For many schools, that alone can seal the deal. Linux offers more, costs less and even can fit well with existing tools. Why in the world wouldn't schools want Linux?

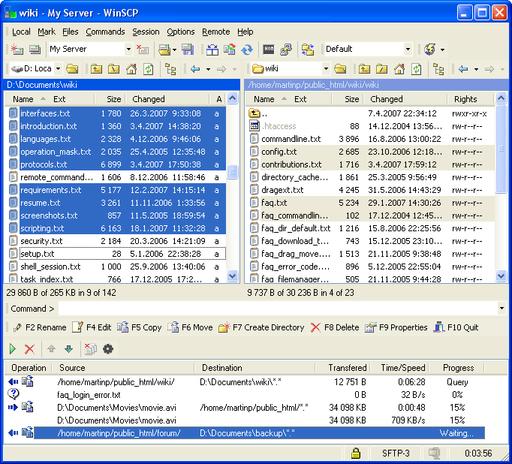

WinSCP is an open-source SFTP, FTP and SCP client for Windows. It provides two GUI interfaces: an Explorer-style interface and a Commander-style interface. You remember Norton Commander, right? In addition, it provides a command-line interface with scripting capability.

WinSCP provides all the expected file operations: uploading, downloading, renaming, deleting, creating directories and so on. It also has the ability to synchronize local and remote directories. You can edit remote files using a local editor. It even gives you the ability to find files on the remote system. The GUI interfaces provide Windows integration: drag and drop, desktop and quick launch icons, “Send To” support and so on.

WinSCP optionally allows you to store configuration information in a configuration file rather than in the registry for making your WinSCP configuration portable. WinSCP also provides U3 support, which is a proprietary method for formatting USB drives and auto-launching applications from them.

WinSCP has been translated into numerous languages. The current stable release is 4.1.9, but version 4.2 may be available by the time you read this (at the time of this writing, the fourth beta version of 4.2 is available).

WinSCP Commander Interface (from winscp.net)

1. Windows XP percent market share: 70.48

2. Windows Vista percent market share: 18.83

3. Windows 7 percent market share (12 days after release): 2.15

4. Mac OS X (all versions) percent market share: 5.27

5. Linux (all versions) percent market share: 0.96

6. iPhone percent market share (O/S market): 0.37

7. Millions of Google hits for Windows: 7,330

8. Millions of Google hits for Linux: 287

9. Millions of Google hits for iPhone: 367

10. Number of preferred “search” languages supported by Google: 45

11. Number of user interface languages supported by Google: 129

12. Number of official languages of sovereign countries: 116

13. Number of sovereign countries: 203

14. Number of Linux 1.0 kernels released: 1

15. Number of Linux 1.2 kernels released: 14

16. Number of Linux 2.0 kernels released: 41

17. Number of Linux 2.2 kernels released: 27

18. Number of Linux 2.4 kernels released: 71

19. Number of Linux 2.6 kernels released (as of 2.6.31.5): 328

20. Sum of above statistics: 2,057.06

7–9: www.google.com

10, 11: www.google.com/preferences

12: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_official_languages

13: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Countries_of_the_world

14–19: www.kernel.org/pub/linux/kernel

20: OpenOffice.org Calc

Few things are harder to put up with than the annoyance of a good example.

—Mark Twain

It won't be covered in the book. The source code has to be useful for something after all.

—Larry Wall

The first 90 percent of the task takes 90 percent of the time, and the last 10 percent takes the other 90 percent of the time.

—The Ninety:Ten Rule

Strange as it seems, no amount of learning can cure stupidity, and higher education positively fortifies it.

—Stephen Vizinczey, An Innocent Millionaire (1983)

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at an Elingsh uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht frist and lsat ltteer is at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae we do not raed ervey lteter by it slef but the wrod as a wlohe.

—Unknown

I am patient with stupidity but not with those who are proud of it.

—Edith Sitwell, quoted in The Last Years of a Rebel (1965)

Even with modern Linux distributions, the inconsistency with onboard audio devices makes using headphones and microphones a hit-or-miss venture. When things work, they work great, but when things don't work, it's generally tough to get them going.

Thankfully, there is an audio standard that seems to work pretty consistently across operating systems: USB. Although the thought of purchasing additional hardware to get sound into or out of your Linux machine might seem a bit frustrating, USB audio devices tend to have better sound quality than the cheap onboard audio devices that come with most laptops and desktops.

Now, because I've given you this tip, you'll probably never need to use it. Still, it's good to know USB audio is very supported under Linux, and the devices are fairly standard. Plus, it's easy to add multiple audio devices with USB audio, which makes things like podcasting much easier!

Late last year, getting a Google Wave invite was reminiscent of getting a Cabbage Patch Kid in 1983. It was the newest gizmo everyone just had to have. As a geek, I was one of the kids begging the loudest. Thankfully, one of our readers from across the pond (Paul Howard, thanks!) sent me an invite, and I cleared my schedule for the product that was going to change the way I communicate. Only, it didn't.

I'll admit, some of the reasons are not Google's fault. First, off, it wasn't even in beta yet. I also didn't really have anything I wanted to communicate with anyone. Even with those two things in mind, I did expect it to be fun to experiment with. Quite frankly, it seemed more cumbersome than helpful.

In watching the demonstrations on the Google Web site, it seems apparent Google Wave was designed to solve some problems we've all faced in e-mail. Where I think Google may have gone wrong, however, is in trying to solve a problem with additional technology that really we've all learned to manage anyway. Sure, Google Wave allows conversations to take place in one section, so everyone can see what's going on, but we've all solved that years ago with “reply all” and “forward”. Yes, Wave allows for embedded photos, videos and so on, but let's be honest, we've all been attaching files and/or links for years.

So what do you think? Am I off-base with my assessment? Is Google Wave changing the way you communicate? If so, I'd love to hear about it. You'll have to send me an e-mail though, because even though I got my Google version of the Cabbage Patch Kid, mine is still in the box.

Sometimes you need to step away from the desktop. Bear with me on this for a sec. Seriously.

Of all the Linux Journal staff members, I may be the least able to separate myself from my electronic life. Now and then I do find it is nice to go back to old-school methods of organizing myself. I ditch the mobile device, the Google apps, the multiple workspaces and use an old-fashioned, awesome Linux Journal wall calendar.

See, we have this other Web site at www.linuxjournalstore.com where you can get all kinds of cool stuff. So you if you'd like a super-cool tricked-out office like I have, kick it old-school with me. Pick up a 2010 calendar and let your geek flag fly.