Have you ever found yourself working on Windows—for whatever reason—and reached for one of your favorite applications from the free software world only to remember that it is not available on Windows?

It is not a problem for some of the best-known free software applications, such as Firefox, Thunderbird, OpenOffice.org, GIMP or Pidgin. However, for some popular Linux applications, such as those from the KDE desktop software project, cross-platform support only recently became a possibility. KDE relies on the Qt toolkit from Nokia, which has long been available under the GPL for operating systems such as Linux that use the X Window System, but it was available under proprietary licenses for Windows only until the most recent series, Qt4. With the release of a GPL Qt for Windows, KDE developers started work on porting the libraries and applications to Windows, and the KDE on Windows Project was born. The project tracks the main KDE releases on Linux and normally has Windows versions of the applications available shortly after.

It is easy to try out KDE applications on Windows. Simply go to the project Web site (windows.kde.org), download and run the installer (Figure 1). You'll be presented with a few choices to make, such as the installation mode (a simple “End User” mode with a flat list of applications or the “Package Manager” mode that is categorized like many of the Linux package managers). You also are given the option of whether to install packages made with the Microsoft compiler or those made with a free software alternative—as many users are likely neither to care about nor understand this option, it may have been better to hide it in an advanced tab.

Next, you are presented with a choice of download mirrors, followed by the choice of which version of KDE software to install. It's hard to imagine why you wouldn't simply want the latest stable release, but the installer gives you a few options and, oddly, seems to preselect the oldest by default.

In the next step, you are presented with a list of applications and software groups available to install, or you can select everything (Figure 2). The installer then takes care of downloading and installing the software, and you don't need to make any further interventions. I did find that the speed of the various mirrors varied greatly; some were up to ten times faster than others. If you're short of time and things seem to be going slowly, it may be worth canceling the download and trying another mirror. The installer is intelligent enough to re-use what you already have downloaded, so you don't really lose anything in this way. When the installation is complete, your new KDE applications are available in a KDE Release subsection of the Windows application menu.

The main KDE 4 distribution for Linux is split into large modules—for example, Marble, a desktop globe application, is part of the KDE Education module with many other applications for subjects ranging from chemistry to astronomy. This works fine on Linux, where most of what you need is installed with your chosen distribution. But, if you're on Windows and want a desktop globe but have no interest in chemistry or physics, there are clear benefits in preserving your download bandwidth and hard-drive space by not downloading everything else. Patrick Spendrin, a member of both the KDE on Windows and Marble projects, says they recognize this issue: “as one can see, we are already working on splitting up packages into smaller parts, so that each application can be installed separately.” Many modules already have been split, so you can install the photo management application digiKam, individual games and key parts of the KDE software development kit separately from their companion applications. The productivity suite KOffice will be split up in a similar way in the near future, and Patrick hopes that the Education module will follow shortly afterward.

Overall, the installation process will feel familiar and easy if you've used Linux in the past. However, if you have used only Windows, the process of using a single installer to install whatever applications you want may seem a little strange. After all, most applications for Windows are installed by downloading a single self-contained executable file that installs the application and everything it needs to run in one go. The KDE on Windows installation process reflects the fact that KDE applications share a lot of code in common libraries.

Patrick explains that individual self-contained installers simply would not make sense at this stage: “the base libraries for a KDE application are around 200MB, so each single application installer would be probably this size.” A version of Marble, however, is available from its Web site as a self-contained installer—the map widget is pure Qt, so it is possible to maintain both a Qt and KDE user interface wrapping that widget. The pure Qt version is small enough to be packaged in this way.

As Torsten Rahn, Marble's original author and core developer puts it, having a standalone installer for the full KDE version of Marble “would increase the time a user needs to download and install Marble; installing the Qt version takes less than a minute.” It might be possible in the future to package a common runtime environment and provide applications as separate executables, similar to the approach taken by Java applications, but Patrick notes that this would take time, as “it would be a lot different from the current Linux-like layout.” In any case, the current approach has some advantages, because it makes you aware of other available applications and allows you to try them out simply by marking an extra check box.

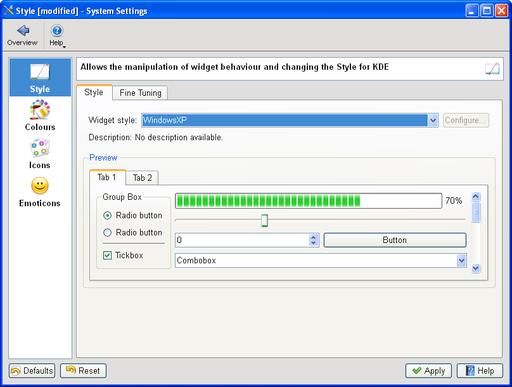

The KDE 4 Windows install comes with a slimmed-down version of the System Settings configuration module (Figure 3), which will be familiar to you if you've used KDE 4 on Linux. Here, you can adjust KDE 4 notifications and default applications in addition to language and regional settings. However, these apply only to the KDE applications, so you can encounter slightly odd situations. For example, if you open an image from Windows Explorer, it will be shown by the Windows Picture and Fax Viewer, but if you open the same file from KDE 4's Dolphin file manager, it will be opened with the KDE image viewer, Gwenview. Of course, you can use the Windows control panel to make Windows prefer KDE applications for opening images and documents and change the file associations for Dolphin so that it will use other Windows programs that you have installed, but you will need to make adjustments in both places to get consistent behavior.

Figure 3. The KDE System Settings module lets you adapt the look and feel of KDE applications to match your system.

System Settings also allows you to choose a selection of themes for your KDE applications, including some that tie in well with the Classic and Luna themes in Windows XP. At present, KDE 4 doesn't include special themes for Windows Vista or Windows 7. However, Windows users are accustomed to using mismatching software from many different vendors, and the KDE applications fit in as well as anything else.

Most of the applications I tried seemed just fine, at least to start with. Konqueror, for example, correctly displayed the selection of major Web sites I visited (Figure 4). However, after using the applications for a while, I began to notice a less-than-perfect integration with the Windows environment. Okular, the KDE document viewer, used the default Windows dialog for open and save, with common Windows folders, such as Desktop and My Documents, available on the left-hand panel. However, other applications, such as KWord, used the KDE file dialog which, in common with the Dolphin file manager, has links on the left-hand panel to Home and Root. These labels probably will not mean a lot to a Windows user unfamiliar with a traditional Linux filesystem layout, and it would be nice to see Dolphin and KDE dialogs modified to show standard Windows folders, such as Desktop and My Documents instead.

digiKam, the photo management application, is one of the real highlights of the KDE world on Linux (Figure 5). On Windows, it started fine, found all my images and allowed me to view a full-screen slideshow. I was able to use its powerful editing tool to crop a photo and adjust the color levels of an image, but when saving the modifications, I received an error that the save location was invalid. digiKam was attempting to prepend a forward slash (as found in a Linux filesystem) to the save location, so that it read “/C:/Documents and Settings...”. A small error, but one that makes practical use of the application difficult.

KOffice2, still experimental on Linux, seemed to run quite well on Windows. I was able to create a document, save it in OpenDocument format and then open it in Okular. Windows users who primarily use Microsoft Office and don't want to use another office suite might consider Okular as a lightweight OpenDocument viewer.

One of my favorite KDE applications on Linux is Kopete, the universal messaging application (Figure 6). I was able to log in to my Windows Live Messenger account and chat to my contacts, but the XMPP protocol (used by Google Talk) wasn't available. Integration with KDE's secure password storage system, KWallet, also seemed imperfect, as I had to go through two rounds of unlocking the wallet before Kopete appeared to have access to the account passwords.

Figure 6. Kopete works well with the Windows Live Messenger service but currently lacks XMPP support on Windows.

Dolphin, the file manager, seemed to work well (Figure 7), and its bread-crumb navigation structure made rapid switches between folders easy. It felt faster than Windows Explorer at loading thumbnails of images, and the preview pane provides excellent file overviews without having to open a dedicated application. If I spent a lot of time on Windows, I would be tempted to try Dolphin as an Explorer replacement. As mentioned previously, Konqueror also handled everything I threw at it.

One notable application missing from the KDE installer is Amarok, the popular music player. The Amarok Web site explains that the Windows port is highly experimental and has been omitted from the KDE 4.3 release of the KDE on Windows installer, although it was available on Windows with KDE 4.2. In fact, no music or video player was available from the KDE installer for version 4.3, which is a shame, as the Phonon technology developed by KDE and integrated into Qt should make it easier than ever before to make such applications truly cross-platform.

KDE 4 comes with a great selection of simple games built in, including the likes of Hangman, Battleships and a few more exotic options, such as Mahjongg (Figures 8 and 9). Windows includes its own applications for playing many of these games, but the KDE alternatives were highly impressive with beautiful artwork. I encountered few problems that would give any indication that they hadn't been designed for Windows in the first place—only some problems saving partially completed games due to differences between the Linux and Windows filesystem structures.

The desktop shell in KDE 4 on Linux is provided by Plasma, a flexible, integrated replacement for the separate desktop, widget and taskbar applications of KDE 3. It is possible to run Plasma as the desktop shell on Windows, but some major features are missing—such as a taskbar—and you need to make some changes to the Windows Registry to try it out. In fact, trying Plasma on Windows really is not a good idea on any machine that you care about, because once you have made the switch, you cannot easily revert it from within your KDE Plasma desktop session. The safest way to try Plasma on Windows is to use a new (and disposable) user account in Windows running in a virtual machine. If you do try it (see the Replacing the Windows Desktop Shell with KDE's Plasma sidebar for instructions), you'll be presented with a pretty KDE desktop (Figure 10) to which you can add a few of your favorite widgets, such as a clock or the KDE menu, run a few KDE applications and, well, that's about it. Windows programs are entirely inaccessible. Although there is a certain wow factor to having an almost complete KDE 4 desktop on your Windows machine, using it is not really practical in any serious way at present.

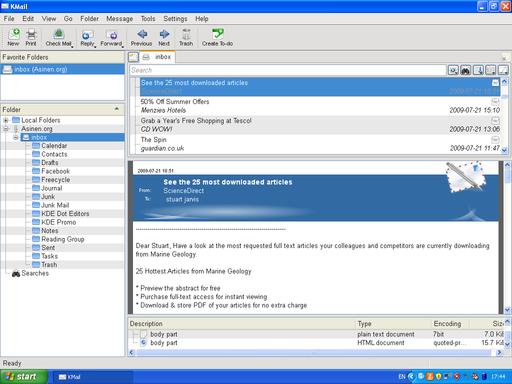

Some of the KDE applications are competing for your attention against better-known alternatives that you easily can install from a single executable file. KDE's Konqueror Web browser, although a fine application, finds itself in a very crowded market for Windows browsers with Internet Explorer already installed and the likes of Firefox, Opera, Safari and Google Chrome all available as alternatives. The potential for some other applications to become popular on Windows is, however, much higher. Kopete faces only Pidgin and the proprietary Trillian messenger as serious competition in the market for multiprotocol messaging clients. Okular is a lightweight but well featured alternative to Adobe Reader. Marble is almost in a class of its own—the nearest competitor perhaps being Google Earth. Kontact, the Personal Information Management suite, also has potential as a compelling cross-platform alternative to existing solutions (Figure 11). Mozilla Thunderbird is a clear competitor, but it lacks comprehensive calendar functionality. Benjamin Dietrich, working in IT support at a German university, who currently has to support many different mail applications across the various computing platforms, believes Kontact could “provide one solution, once it is as mature as it is on Linux”. However, a way to distribute Kontact as a self-contained installer easily would add to its appeal: “a single binary installer would be perfect.”

Figure 11. KMail, part of the KDE Kontact Personal Information Management suite, was able to connect to my mail server and download my e-mail.

The spread of KDE applications to Windows also has had benefits for the wider KDE Project. Amarok's integration with the Last.fm music service was largely put together by a developer who used Windows rather than Linux. It is unlikely that he would have become involved if it had not been possible at the time to run Amarok on Windows. Getting exposure to users on Windows also gives KDE the potential to attract users to trying KDE 4 on Linux and should make the transition for such users easier if they already know some of the applications.

The KDE on Windows Project still is quite young, and there are plenty of rough edges in many of the applications and some notable gaps in the application line-up. However, the installation process works well and is straightforward for anyone who has used a package manager on Linux. Although the installation process is different from that of most Windows applications, the installer is sufficiently well designed that it should not cause problems for most Windows users. The recent and continuing work to split up applications so that users can install exactly what they want also lowers the barriers to trying out KDE applications in Windows. Some of the applications have great potential to fill gaps in the Windows application world, particularly as free software alternatives to proprietary applications. As the project Web site freely admits, many of the applications may not yet be ready for day-to-day use, but they are well worth checking out and will only get better.