The Linux scheduler is pretty controversial, in large part because contributors can test their code and find it to be faster than someone else's code, and that other person can run tests showing the exact opposite! It all depends on what you test for. Some tests examine only how many processes can be created in the shortest amount of time. Other tests try to mimic interactive behavior and examine how smooth that behavior is. When you add to this the fact that the scheduler needs to work as well as possible for the full range of computer hardware that might be running Linux, the problem becomes far more complex. It's no small wonder that disagreements become heated, and some contributors choose to go off and code on their own and abandon the quest to elevate their scheduler to the status of Official Linux Scheduler.

In that spirit, Con Kolivas has been quietly writing BFS (Brain F*** Scheduler), incorporating everything he's learned about schedulers over the years. But, his work recently got the attention of Ingo Molnar, maintainer of the current in-kernel scheduler, and the ensuing discussion highlighted some of the issues surrounding scheduler coding. For example, one of Con's main goals with his scheduler was to make the user interface as smooth as possible for desktop systems—that is, systems with eight CPUs or thereabouts. He wanted to play games, listen to music and do other highly interactive things, without having a jerky display. His technique was (among other things) to abandon support for systems that had thousands of CPUs onboard.

Clearly, Linux has to support both small and large systems, so Con's scheduler wouldn't work as the primary in-kernel process scheduler. And, because Linus Torvalds has said he doesn't want to include multiple schedulers in the kernel, it's unlikely that Con's code ever could be included in the official tree. So he's been coding it up on his own, working with a small group of interested users who don't mind patching their kernels to get the smoothest possible performance.

It seems like a very cool project. Maybe at some point, his code will be offered as an option to desktop users. But for the moment, the kernel has to stay with the scheduler that supports the most systems and that attempts to have the broadest possible range of decent performance.

The VMware folks are discontinuing VMI support. Virtualization features in hardware are making it pointless to try to do the same thing in software. Hardware virtualization probably will be everywhere soon, they say, so there's no reason for VMI to emulate multiple CPUs in software anymore. Alok Kataria asked on VMware's behalf about the best way to deprecate and remove the VMI code from the kernel. As it turned out, the best way is going to be to keep supporting it for another year or so, until it truly has no more users. In the meantime, VMI is being added to various lists of features that are soon to be removed, and code is being added to alert users that they should brace for the time when VMI no longer will be available. Kudos to VMware for working with the kernel folks to find the best way to do this. It's nice to see industry paying attention to open-source methods.

CPUidle is a new project by Arun R. Bharadwaj that attempts to save power on PowerPCs by recognizing when CPUs are idle enough to put into low power modes. It does this by analyzing the current system usage and essentially making educated guesses about what's going to happen in the near future. In addition to being a cool and useful project, we can look forward to many future flame wars surrounding exactly how to determine when to put a CPU into a low power mode, as hardware designs and software usage patterns become more and more complex.

Jakub Narebski took a survey of Git users and made the results available at tinyurl.com/GitSurvey2009Analyze. Thousands of people participated, virtually all of whom are happy with it. It's interesting to see that 22% of respondents use Git under Windows. If you haven't tried Git yet, or if it's been a while, you really should check it out. It takes a problem that stumped many people for years and makes it look easy. The flame wars, the bitter competition between projects and the venomous BitKeeper disputes have all melted away. Git is a tool of peace.

Whether you love Netbooks or hate Netbooks, there's no doubt that Intel currently owns the market when it comes to providing the hardware. Unfortunately, Intel's attempts to make CPUs that consume less power also have resulted in Netbook computers that are painfully slow. And, don't get me started on the GMA500 video chipset. (Actually, feel free to read my rant on the Linux Journal Web site regarding the GMA500 chipset at www.linuxjournal.com/content/how-kick-your-friends-face-gma500.)

Thankfully for users, while Intel works to tweak its Atom line of processors, other companies are working to enter the Netbook market too. Unfortunately for Intel, one particular company has more experience with low-power, high-performance computing than Intel could ever fathom—ARM. Ironically, while Intel keeps pushing its clock speeds down to save a bit of power, ARM has been ramping its speeds up. Intel's latest Atom processor, at the time of this writing, has a whittled-down speed of 1.3GHz; the new ARM-based CPUs are around 2GHz.

Certainly, Intel has reason to fret as the embedded market, which is dominated by ARM, begins to scale up to the Netbook market. The real fear, however, should be that once ARM invades the Netbook and notebook markets, there is no reason for it to stop. Imagine racks of servers with ARM-based CPUs operating at Intel-class speeds while sipping electricity and staying cool enough to run without heatsinks. Oh yeah, guess who else might be a little afraid? That's right. Windows doesn't run on the ARM architecture, but Linux sure does.

In the November 2009 issue, I looked at some tools used by computational scientists when they are doing pre- and post-processing on their data. This month, I examine ways to automate this work even further. Let's start with the assumption that we have a number of steps that need to be done and that they need to be done on a large number of data files.

The first step is to find out which files need to be processed. The most obvious way to do that is simply to create the list of files manually. Doing it this way is the most time-intensive, and as with all manual operations, it can lead to mistakes due to human error. This step lends itself to automating, so it should be automated. The most popular utility for creating lists of files is the find command, which finds files based on a number of different filters.

The most common filter is the filename. You can use find to locate where a certain class of files lives on your drive. Let's say you have a group of data files that need to be processed, all ending in .dat. The find command to search for them would be the following:

find . -name "*.dat" -print

The first option tells find where to start looking for files. In this case, you are telling find to start looking in the current directory. You also could give it any directory path, and it would start its search at that location. The second option, -name, tells find what to filter on. In this case, you are telling find to filter based on the filename. This filter is actually a filename pattern, "*.dat". This pattern needs to be quoted so the shell doesn't try to expand the * character. The last option, -print, tells find to print the search results to standard output. You can redirect this to a file or pipe it to another command. By default, find separates the filenames with new-line characters. A problem can occur if you have odd characters in your filenames, like blanks or new lines, and you feed this as input to another program. To help mitigate that issue, use the -print0 option instead of -print. This tells find to separate the results with a null character rather than a new-line character.

There are many other filter options. The first one to be aware of is -iname. This is like -name, except that it is case-insensitive. There also is a group of filter options around time: -amin n and -atime n filter based on access time. -amin n looks for files that were accessed n minutes ago. -amin +n looks for files that were accessed more than n minutes ago, and -amin -n looks for files that were accessed less than n minutes ago. The -atime n option looks for files that were accessed n*24 hours ago. Again, +n and -n behave the same way. The same tests can be made using -cmin n and -ctime n to test the file's created time, and -mmin n and -mtime n test the modified time of a file. The last filter option to use in this instance is -newer filename. This option checks to see whether the files being searched for are newer than some reference file named filename. This might be useful if you want to generate a list of files that have been created since your last processing run.

Now that you have your list of files, what do you do with it? This is where you can use another command called xargs. xargs, in its simplest configuration, takes lines of input and runs some command for each line. This simplest use looks like this:

xargs -I {} run_command {}

Here, xargs reads lines of input from standard input. The -I {} option tells xargs to replace any subsequent appearances of {} with the line of input that was just read in. Using {} isn't mandatory. You can use any characters to act as placeholders. In this example, xargs executes run_command {} for each line of input, substituting the input line into the place held by {}. If you dump your list of files into a text file, you can tell xargs to use it rather than standard input by using the -a filename option. Also, xargs will break input on blanks, not just new-line characters. This means if your filenames have blanks in them, xargs will not behave correctly. In this case, you can use the -0, which tells xargs to use the null character as the delimiter between chunks of input. This matches with the -print0 option to find from above. If you aren't sure whether the given command should be run on every file listed, you can use the -p option. This tells xargs to prompt you for confirmation before each command is run. The last option to xargs that might be useful is -P n. This option tells xargs to run n number of commands in parallel, with the default value for n being 1. So, if you have a lightly loaded dual-core machine, you might want to try using -P 2 to see if the processing happens a bit faster. Or on a quad-core machine, you might want to try -P 4.

Putting this all together, let's look at a hypothetical job you may have to do. Let's say that you have a series of data files, ending in .dat, scattered about your home directory. You ran a processing job last week and named the file containing the list of filenames to be processed list1.txt. Now, you want to process all the data files that have been created since then. To do so, you could run the following commands:

find ~ -name "*.dat" -newer list1.txt -print >list2.txt

xargs -a list2.txt -I {} run_processing {}

This way, you would have a list of the files that had just been processed stored in the file list2.txt, for future reference. If some of the filenames contain blanks or other white-space characters, you would probably run the following instead:

find ~ -name "*.dat" -newer list1.txt -print0 >list2.txt

xargs -a list2.txt -I {} -0 run_processing {}

Hopefully, this helps you automate some of the routine work that needs to be done, so you can get to more interesting results. Go forth and automate.

It's obvious to most Linux users that Digital Rights Management (DRM) is a really bad idea. It's not just because DRM-encoded media usually won't play with our operating system, but rather because we understand the value of openness. The really sad part is that DRM, at least on some level, is attempting to do a good thing.

Take Wil Wheaton for example. You may know Wil from television or movie acting, but he's also a successful writer. Along with writing books, he often performs them and sells the audiobook version of his work. Because Wil is against DRM, his books are available as unrestricted MP3 files. That's great for those of us who like to listen to such things on Linux or a non-iPod MP3 player. Unfortunately, some users confuse DRM-free with copyright-free. When otherwise decent individuals don't think through the ramifications of redistributing someone's copyrighted work, you end up with situations like this: tinyurl.com/stealfromwil.

If you put yourself in Mr Wheaton's shoes for a second, you can see how tempting it is for authors—and, more important, publishing companies—to DRM-encode their work. Theoretically, if a piece of media is “protected” with DRM, only those people who purchase the rights to enjoy it can enjoy it. Unfortunately, as everyone but the big companies that insist on using it know, all it manages to do is punish the honest people. People who have tried to play Amazon Video on Demand videos on their Linux desktops or listen to Audible audiobooks on their no-name MP3 players know exactly what I mean.

The truth of the matter is, if people are dishonest enough to use copyrighted materials they haven't paid for, DRM does little more than give them an “excuse” for their pirating ways. Right now, users are given the choice of paying money for limited, restricted access to media, or to download illegally fully functional, cross-platform, unrestricted media for free from torrent sites. I have two messages for two different groups:

Media publishing companies: make it easy for users to buy access to your media, and make that media flexible, archive-able and affordable. Yes, people will pirate your stuff—just like they do now. The difference will be that your honest clients won't hate you, and you'll actually gain some clients because you will be offering what people really want.

Frustrated users: look, I'm with you. DRM frustrates me too. Although I'm not expecting to convert those among us who choose to pirate media, I would hope that we'd all support those companies (and individuals, in Wil Wheaton's case) that “get it”. The only way we'll be part of the solution when it comes to eliminating DRM is actually to buy non-DRM stuff. At the very least, every time you pirate something because you can't buy it legitimately, e-mail the companies and let them know. If they see lost sales, perhaps they will rethink their approach to digital media.

I could go on and on about the insanity of Blu-ray DRM and the like, but I don't have the energy. Plus, I want to go watch the hi-def movie I just ripped on my Linux laptop. I'll have to remember to e-mail the movie producer about my morally justifiable, but legally questionable ways....

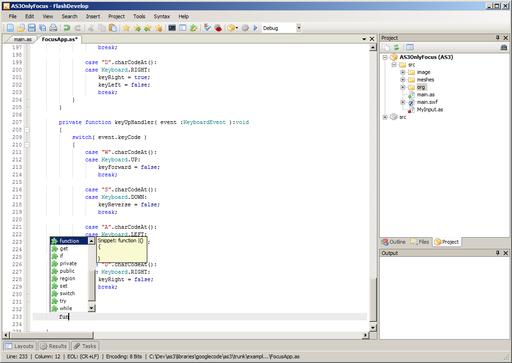

FlashDevelop is a free and open-source code editor designed for developing Flash applications. It supports code snippets, code completion, code navigation, code generation, bookmarks, task handling and syntax highlighting for ActionScript 2 and 3, MXML and haXe. It contains an integrated Project Manager and project templates to get your projects off the ground quickly.

FlashDevelop integrates with the Flash CS3, Flex SDK, Mtasc and haXe compilers. It can execute the compiler and parse error/warning output for quick access to the offending code. FlashDevelop has a plugin architecture for extending it and integrating it with other tools as well.

The editing power behind FlashDevelop is provided by the open-source Scintilla editor library. The Scintilla library was first released in 1999 and provides the editing capabilities in a number of open-source projects, such as Notepad++, Notepad2 and Open Komodo.

FlashDevelop is a .NET 2.0 application, and it runs on Windows XP and newer versions of Windows. Currently, the only way to run it on Linux or OS X is via virtualization software—which is to say, it currently will not run on Mono. FlashDevelop is released under the MIT License. The current version is 3.0.4.

FlashDevelop Code Snippets (from flashdevelop.org)

1. Year that the :) emoticon was invented (September 19): 1982

2. Year the Internet was first proposed (May 22): 1973

3. Twitter year-over-year percent growth rate (February 2008 to February 2009): 1,382

4. Twitter monthly visitors in millions: 7.0

5. Facebook monthly visitors in millions: 65.7

6. MySpace monthly visitors in millions: 54.1

7. Club Penguin (Disney not Linux) monthly visitors in millions: 6.1

8. Percent of Twitter users that fizzle out during the first month: 60

9. Percent of Twitter users that fizzled out before Oprah: 70

10. Percent of Facebook and MySpace users that fizzle out: 30

11. Percent of US farms that had Internet access in 1999: 20

12. Percent of US farms that had Internet access in 2007: 57

13. Percent of US farms that had Internet access in 2009: 59

14. Percent of US farms that use satellite for Internet access: 13

15. Percent of US farms that use cable for Internet access: 13

16. Percent of crop farms that use computers in their business: 45

17. Percent of livestock farms that use computers in their business: 37

18. Number of LJ issues since the first National Debt figure appeared (September 2008): 17

19. Change in the debt since then (trillions of dollars): $2.54

20. Average debt change per issue (billions of dollars): $149.7

1, 2: www.distant.ca/UselessFacts

3–10: Nielsen Online

11–17: NASS (National Agriculture Statistics Service)

19–20: Math

The Itanium approach...was supposed to be so terrific—until it turned out that the wished-for compilers were basically impossible to write.

—Donald Knuth

This continues to be one of the great fiascos of the last 50 years.

—John C. Dvorak, in “How the Itanium Killed the Computer Industry” (2009)

We decided to innovate our way through this downturn, so that we would be further ahead of our competitors when things turn up.

—Steve Jobs, as the 2001 recession was fading

IBM is the company that is notable for going the other direction. IBM's footprint is more narrow today than it was when I started. I am not sure that has been to the long-term benefit of their shareholders.

—Steve Ballmer (during the last ten years, IBM's share price has increased by 30%, and Microsoft's has decreased by 30%)

We're in it to win it....IBM, we're looking forward to competing with you in the hardware business.

—Larry Ellison (in a response to IBM's spreading of FUD over Sun's future after the Oracle buyout)

The longer this takes, the more money Sun is going to lose.

—Larry Ellison (Sun's revenues have fallen dramatically since the buyout was announced. Sun is losing about $100 million a month as European regulators delay approving the buyout)

We act as though comfort and luxury were the chief requirements of life, when all that we need to make us happy is something to be enthusiastic about.

—Einstein

While we haven't won yet, Red Hat will continue fighting for the good of technology and for the good of innovation.

—Jim Whitehurst, President and CEO, Red Hat (referring to the Bilski case)

At the Linux Journal Web site, we've been providing tech tips for quite some time. Although there seems to be no end to the tips we come up with (thanks in part to user contributions), lately we've decided to step it up a notch. We certainly will continue to provide command-line tips, GUI shortcuts and unconventional Linux tips, but we're also adding some practical real-world tips as well. Whether you need to brush up on cable-crimping skills or figure out how to track down a rogue DHCP server, you'll want to catch our new tech tips.

As always, you can find our videos on our main Web site: www.linuxjournal.com.

See you there!

Now that you are fully immersed in all things ham-related, join us on-line for more ham radio discussions at www.linuxjournal.com/forums/hot-topics/ham-radio. Correspond with other Linux enthusiasts who share an interest in Amateur Radio and discuss related open-source projects. Drop us a note in the forum, and let us know what projects you are working on, more about your radio interests and any advice you may have for other operators.

Further resources also are available at www.linuxjournal.com/ham. Whether you are a newcomer or an experienced ham, we hope you'll find LinuxJournal.com to be a valuable resource as you delve further into your radio operations.