Enough with the cloud nonsense. Sure, you can buy in to some big commercial cloud, but odds are you've already got one of your own. Why not take advantage of it and get yourself backed up safely?

Our guests will be here any moment, François. What have you done with all the tables and chairs on the patio? Yes, I guessed you moved them to make room, which brings me to my second question. What are all these model rockets doing out here on the patio? Wait a minute. Are those USB Flash drives I see taped to the rocket bodies? Why, in the name of all that is free and open, are you planning to launch all those Flash drives? Quoi? What do you mean, you are doing what I asked you to do?

Mon Dieu! When I asked you to back up the restaurant's machines to our cloud, I didn't mean actual clouds. A cloud is just a fancy word for somebody else's network or network resources. More accurately, a cloud is a kind of marketing term to describe computing or storage resources provided by a vendor over the Internet. I was using the term in jest, partly because people seem rather obsessed with running their operating systems in the cloud, backing up their servers to the cloud and so on. The restaurant's network isn't on par with Google or Amazon, but we have plenty of storage space, mon ami. I see our guests arriving. Vite, François! Inside!

Good evening, everyone, and welcome to Chez Marcel, where exquisite wines are paired with the finest in Linux and open-source software. Please, take your seats and make yourselves comfortable while François cleans up his model rockets. We have a lovely 2006 Kim Crawford SP Flowers Sauvignon Blanc from New Zealand—a full-bodied dry white with intense flavor and a long finish...unforgettable. François, take those rockets to the cellar and return with the wine. Merci, mon ami.

While my faithful waiter fetches the wine, I probably should tell you that all those model rockets were an attempt at a cloud backup solution. There are, of course, numerous backup solutions you can use, from the simple and free to the complex and expensive, as well as everything in between. The technology behind most backup systems, however, tends to be much more limited. Using classic tools, such as tar and gzip, to back up and compress is still very common under the surface of much more complex tools. This is true even when using network resources. In the end, you are backing up from one machine to another. Many people I know, including those with small businesses, do this for their regular backups. Machine A backs to machine B, which backs to C, which backs to A. The machines, and their drives, are all part of a network. Hey, instant cloud, and you probably didn't know you had one.

This is where rsync, another popular backup tool, shows its worth. As the name implies, rsyncs keep a backup copy of your data, in sync with the original. It can do it locally, from one physical drive to another, or across your network. Because only those files that have been modified are transferred, the process can be very quick. You can do this with single files, whole directories and subdirectories, while maintaining file ownership and permissions, links, symbolic links and so on. rsync has its own transport, or you can use OpenSSH to secure the transfer, and (of course) there are some great front-end, graphical tools to make the process a little slicker.

You can find rsync at rsync.samba.org, but you probably don't even have to look that far. Many distributions load it when you install your system. If not, check your installation disks or simply pick it up from your distribution's repositories. Before I explain how to rsync your data to your own personal cloud, let me show you how easy it is to create a synchronized backup of your data from one directory to another (or one drive to another):

rsync -av important_stuff/ is_backup

In the above example, rsync copies everything in the directory important_stuff into another directory (or folder) called is_backup. Most of you will have figured out that the -v means verbose copy. The -a option hides some amount of complexity in that it is the same as using the -rlptgoD flags. In order, this means that rsync should do a recursive copy; copy symbolic links; preserve permissions, modification times and group and owner information; and, with the final D, copy special files (device and block). When you press Enter, files go scrolling by, after which you see something like this:

sending incremental file list ./ CookingJul08.tgz CookingJul2008_albums.odt CookingJul2008_albums.txt igal_page.png montage.png shalbum.png zenphoto_comment.png zenphoto_go.png zenphoto_login.png zenphoto_makepass.png zenphoto_setup.png zenphoto_theming_comment.png zenphoto_upload_photos.png zenphoto_view_album.png . . . . sent 46059880 bytes received 2753 bytes 6141684.40 bytes/sec total size is 46044132 speedup is 1.00

One other thing that rsync should be able to do in order to be completely useful is delete files. If you are mirroring files and directories, it stands to reason that you want the mirror to represent exactly what is on the original. If files have been deleted, you want them deleted on the backup server as well. This is where the --delete parameter comes into play. Using the earlier example, let's delete that tgz file from the original, then relaunch the command:

$ rsync -av --delete important_stuff/ is_backup sending incremental file list ./ deleting CookingJul08.tgz sent 4164 bytes received 25 bytes 8378.00 bytes/sec total size is 41911050 speedup is 10005.03

From here on, both directories will always be in sync. When doing network backups, this magic synchronization of files and directories is done using a client and server setup. At least one machine must play the role of server (although nothing is stopping you from running an rsync dæmon on every one of your machines). The server gets its information about who can access what from a configuration file called rsyncd.conf. You'll find that it probably lives in the /etc directory. The following partial listing is from one of my rsync servers:

hosts allow = 192.168.1.0/24

use chroot = no

max connections = 10

log file = /var/log/rsyncd.log

gid = nogroup

uid = nobody

[marcel]

path = /media/bigdrive/backups/marcel

read only = no

comment = Marcel's files

[francois]

path = /media/bigdrive/backups/francois

read only = no

comment = Files for the waiter

This configuration file is quite simple once you get the hang of it. Backup areas are identified by a name in square brackets (marcel, website, francois and so on). The chief bits of information there include the path to the disk area and some kind of comment. Notice that I specified read only = no, but I could just as easily have added that to the top section (the one without a name in square brackets). That's the global section. Anything put up there applies to all other sections, but it can be overridden. Pay particular attention to the gid and uid values; these are the group ID and user ID to which the file transfer takes place. The default is nobody, but you need to make sure that is correct for your system. One of my servers does not have a nobody group, but has a nogroup group instead.

The hosts allow section identifies my local subnet as being the only set of addresses from which transfers can take place. The log file line identifies a file to log information from the dæmon. You also can specify a maximum number of connections, specific users who are allowed to transfer files (auth users) and a whole lot more. Run man rsyncd.conf for the full details. When your configuration is set, you can launch the rsync dæmon, which, interestingly enough, is exactly the same program as the rsync command itself. Just do the following:

rsync --daemon

That's it. Now, it's time to put this setup to use. You might want to test your rsync connection by issuing the command:

rsync remote_host::

Note the double colon at the end of the server's name. The result should be something like this, assuming a server called thevault:

$ rsync thevault:: website All our websites francois Files for the waiter marcel Backup area for Marcel

Now, pretend I am on the server where my Web site files live. Using the following command, I can launch rsync to back up this entire area:

rsync -av /var/www thevault::website/ building file list ...

The format of the rsync command is rsync options source destination, which means I also could start the command from thevault, assuming my Web site machine also was running an rsync dæmon. The result would look more like this:

rsync -av localbackupdir websitemachine.dom::websites

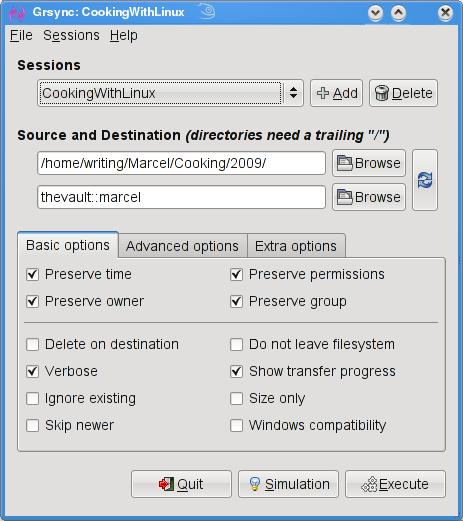

All this work at the command line is great, but there are some tools for making the process easier, particularly if you will be creating a number of rsync backups or if you want to get into more complex requirements, such as scheduled backups. A friendly graphical front end on your desktop also may be a greater incentive to perform regular backups or take a quick backup when you've added important data and a “right now” backup is desirable. The first tool I want to show you is Piero Orsoni's grsync (Figure 1).

Figure 1. grsync provides an easy-to-use interface with every rsync option you could want.

While providing a great front end to rsync, grsync also works as a teaching tool for the command-line version of the program, or at least it helps as a memory aid. Almost any command-line option available to rsync is covered in one of these three tabs: Basic options, Advanced options and Extra options. What makes it a learning tool is that if you pause over any of those check boxes with your mouse, a tooltip appears showing the command-line option with a brief description of its function.

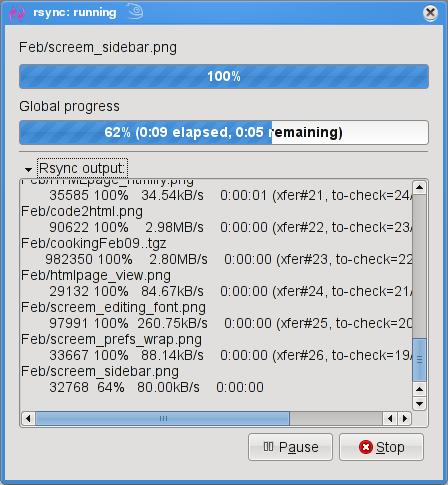

To start, click the Add button next to the session drop-down dialog and enter a name for your backup. You can define many different rsync backups here, and then launch them again at a later time. Clicking the Browse button brings up the standard Gtk2 file browser window from which you can select your local and destination folders. Unfortunately, you can't browse remote systems, but if you've already set up an rsync server, have no fear. You can enter it manually in the format I showed you earlier (for example, thevault::marcel/). When you are happy with the various options, click Execute. If you only think you are happy, click the Simulation button. (Chef Marcel loves a program with a sense of humor.) When you do click Execute, the program switches to a progress window (Figure 2), so you can see where you are in the process.

Figure 2. Once your grsync backup begins, it switches to a progress report view.

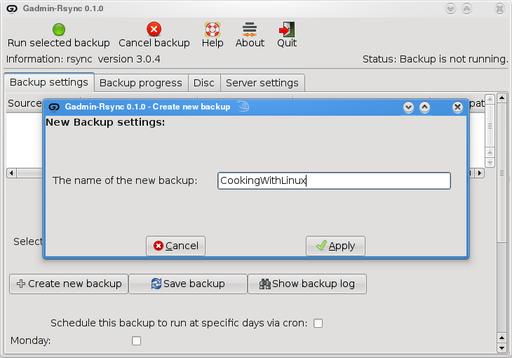

The next item on our rsync menu is Magnus Loef's GAdmin-Rsync. GAdmin-Rsync makes every aspect of creating an rsync backup a matter of filling in the blanks. What's more, the program creates backups using SSH by default, which means you can set up rsync backups to any machine to which you have secure shell access. This also means you don't actually need to have an rsync dæmon running on the remote machine if you have SSH access. Let me show you how it works.

When you start the program for the first time, you'll be asked for a name to give your new backup (Figure 3). You could back up the entire system or select specific folders of filesystems. Choose a name that makes sense to you based on what you want to back up. Enter a name, then click Apply to continue.

Figure 3. GAdmin-Rsync lets you define numerous backup configurations, each with its own identifier.

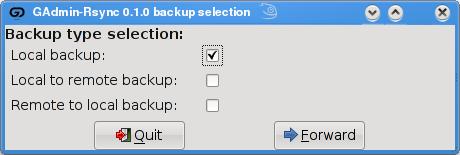

As you saw when we did this at the command line, rsync backups can be local, to a remote system or from a remote system. The next window looks for that very information (Figure 4). By default, local backup is checked. To back up to a remote server, select Local to remote backup. Because you can swap source and destination easily when using rsync, there's that third option. I routinely use a remote to local backup for my Web sites and remote systems. Click Forward to continue.

Figure 4. Your next step is to define the location of the backup.

Assuming you chose to back up to your cloud, your next step is to enter the server information (Figure 5). This includes the backup path on your networked server as well as your SSH key type and length. When you have entered this information, click Forward.

Now you're ready to start the rsync backup. Click the Backup Progress tab to watch all the action.

What is nice about this program is that you can (as with grsync) store a number of backup definitions, so you can choose to back up your documents, music or digital photographs when it suits you. GAdmin-Rsync goes further though. If you take a look down at the bottom of the window on the Backup settings tab, you'll notice the words “Schedule this backup to run at specific days via cron” and a check box (Figure 6). Check the box, then scroll down to choose the days you want the backup to run. A little further down, you can specify the time as well.

Well, mes amis, closing time has caught up to us, and at least for now, time is one thing we can't back up. Despite the hour, I am quite sure we can convince François to refill our glasses one final time before we go our separate ways. Please, mes amis, raise your glasses and let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé! Bon appétit!