Linux visual effects artists around the world create a new sci-fi classic.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is a re-invention of the 1951 science-fiction film classic. Keanu Reeves stars as the benevolent visiting alien Klaatu, come to Earth to warn us to change our barbaric ways or face destruction.

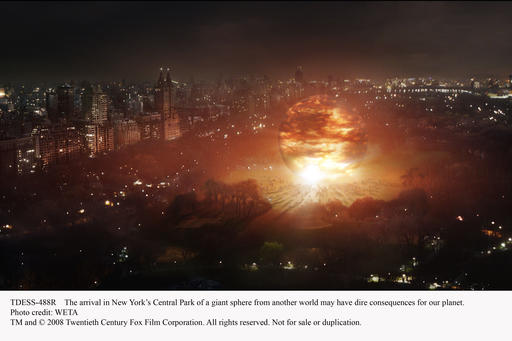

The arrival in New York's Central Park of a giant sphere from another world may have dire consequences for our planet. Photo credit: WETA.

Klaatu's (Keanu Reeves) arrival on Earth via a giant sphere triggers a global upheaval. Photo credit: WETA.

Ten years ago, Titanic was the first film to use Linux in a big way. Today, Linux dominates big-budget visual effects and 3-D animation. Ever since The Matrix, it's become routine to have several visual-effects companies working on the same film. A visual effects supervisor at the studio, in this case Fox, selects which companies will create the visual effects.

“I came in and met with the director Scott Derrickson”, says The Day the Earth Stood Still Visual Effects Supervisor Jeffrey A. Okun. “In Scott's opinion, and one I agree with, the day of visual effect as star of the movie is gone. He wanted to focus on story. He wanted spectacular effects that were invisible. When dealing with spaceships, aliens and giant robots, that's a bit of a challenge.”

“Weta was our primary group on the film that did 220 shots on the film”, says Okun. “Then Cinesite. We had Flash Filmworks and CosFX. Later on we added Hammerhead and Hydraulx, a company called At the Post, and a couple other little companies. Weta handled the Sphere, the alien, the robot and the Swarm. It's all particle systems based on chaos theory. That means it's render-intensive.”

“There's a shot of the Sphere that we call the super-sphere shot”, says Okun. “That starts in the swamp and takes you to various Spheres activating around the world. That took 30 days to render. That's pretty crazy. It's around 1,100 frames. It's an amazing shot. You don't want to show it to the director at the end of the day and have him say, 'That's not really our sphere'...which is what happened. We came up with a patch system at Weta Digital where we could render a section and patch it over the offending thing. This particular patch took three days to render.”

“Linux is an integral part of what we do here at Weta”, says Production Engineering Lead Peter Capelluto. “It's very well suited for the dynamic needs of the visual-effects industry. Our department would have a much more difficult time accomplishing our goals with any other operating system.”

“Weta predominantly uses Linux for our workstations and also for our renderfarm and servers”, says Capelluto. “There are a few applications that require the use of Mac OS X, Windows and Irix. Whenever possible, we use Linux. The open-source nature of Linux and the many Linux applications are a major advantage. We also prefer it for stability, low cost, access control, multiuser capabilities, control and flexibility.” Capelluto's department develops pipeline software, such as the digital asset management system and the distributed resource management system for their renderfarm.

“We have 500 IBM Blade Servers, 2,560 HP BL2x220C Blade Servers and 1,000 workstations”, says Weta Digital Systems Department Lead Adam Shand. “Ubuntu is our primary render and desktop distro. We also use CentOS, RHEL and Debian.” The workstations are IBM and HP. Weta uses NetApp DataOnTap, NetApp GX, BluArc, Panasas and SGI file servers. Storage is mostly NAS, not SAN. For open-source apps, they use Apache, Perl, Python, MySQL, PostgresSQL, Bind, OpenOffice.org, CUPS, OpenLDAP, Samba, Firefox, Thunderbird, Django, Cacti, Cricket, MRTG and Sun Gridware.

“We're big fans of open-source code here at Weta”, says Capelluto. “We're utilizing Sun's Grid Engine for distributed resource management and have helped them fix a number of bugs. It's very powerful to be able to improve upon open-source software and to fix any problems you encounter.”

“When your supervisor is in New Zealand and your editor is in Los Angeles, it makes things a bit harder”, says Cinesite Visual Effects Producer Ken Dailey, who is based in London. “I'd talk to Jeff every day and make sure he has the right Quicktimes, that everyone is looking at the same stuff. Time was the biggest challenge. The reaper shot in New York came very late. I think we had three weeks from the time we got the plates. We shared Maya models with Weta. We sent them our reaper model and they shared models with us.”

“We did about 60 shots”, says Dailey. “We did where Klaatu is being interrogated, which shows how he can take control of electrical systems. Later in the movie, there's a sequence where the military decides to attack Gort in Central Park with drones. We had 3-D tanks and explosions. We did the big tilt-down from space at the beginning of the movie.”

“We're principally using Maya, Shake and RenderMan”, says Dailey. “Shake is running on Linux. Maya is running mostly on Windows. We use a bit of Photoshop on Windows.” Cinesite uses Maya on Linux and Windows. However, the range of available plugins is far greater on Windows. The 3-D painting package MudBox is the main one. That's recently been bought by Autodesk and may be coming to Linux.

“We have about 80 desktop systems running Linux”, says Cinesite Senior Systems Administrator Danny Smith. “We have at least a couple hundred render systems. All of those are IBM Blade systems. We have about 40 Windows systems as well. Our principal requirement for Windows is Photoshop. There's no way to run Photoshop reliably in its latest release on Linux with CrossOver. The main reason for Photoshop is the color depth—the full 16 bits we require for film work in matte painting and dealing with textures.”

“CinePaint was looked at in the past, back when it was Film Gimp”, says Smith. “Our biggest problem with it is finding people with the skills to use it. People walking in the door already know Photoshop. People would be more interested in GIMP or CinePaint if it was more like Photoshop. If we could find a tool that reduces our Photoshop costs, a lot of people would be very happy. We have 20 or 30 seats of Photoshop.”

“Shake is a product that's being discontinued”, says Smith. “Even though we've done the site buyout, as soon as Apple launches a competing product, they have the right to discontinue our use of Shake. The likely successor is Nuke. We're trying to get people up to speed with Nuke and doing more and more with it. It takes time to train people. It's slowed down our adoption.”

“We mostly run Red Hat Fedora”, says Smith. “We're on version 4, migrating to 8. We've experimented with SUSE. The reason to stay with Red Hat is support from software vendors. We're paying for that support, and it's mission-critical.”

For dailies playback, Cinesite is using the Windows system Scratch from Assimilate. Scratch also is being used by the Avid editors in Los Angeles on the Fox lot. Smith had the Linux SpecSoft RaveHD dailies system at his prior company, but considers the California startup too far away to support London. Cinesite also uses FrameCycler on Linux for movie playback. They have NetApps and Isilon file servers.

“We had Flash Filmworks handle a hundred shots, 3-D helicopters and stuff like that”, says Okun. Flash Film Works, based in Los Angeles, has its desktops set up to dual-boot. “This was one of the rare occasions where most of the workstations stayed in Windows”, says Flash Film Works Technology Chief Dan Novy. “That's mostly because we weren't doing a lot of fluid dynamics simulations. The renders were 80% Windows. I didn't need the high performance that I normally use 64-bit Fedora for. The file servers are all Linux. I have a specialized Shake station that has The Foundry Furnace suite on it for doing automation.”

Even running Windows, they still are using open-source tools. “Fusion 5 added Python in addition to its Lua-based Ion scripting”, says Novy. “That can do a lot more automation, getting renders to the editor automatically, that sort of thing.” Fusion recently has become available on Linux, but Lightwave is Windows. Flash Film Works likes Lightwave's free render nodes. A Maya RenderMan node would cost them $4,000–$5,000; Mental Ray costs $1,200.

“I personally run Ubuntu on my laptops”, says Novy. “But, for setting up file servers, I'm so used to the Red Hat paradigm. We have one Isilon cluster, a FreeBSD variant. Each node is 1.4TB. I have five nodes and one backup. It's old, and I'm leaning toward BluArc to replace it. We have about 100 CPUs on the farm and about 50 desktops.” Flash Film Works backs up its data to Blu-ray.

“Hammerhead did a handful of really difficult and excellent shots”, says Okun. “They did one really difficult 3-D helicopter with the Secretary of State on it. They did a matte painting that was really 'saving the day' that had an automobile factory. They did the trooper-healing shot.”

“Hammerhead uses Linux for all of our graphics workstations for our visual-effects artists, as well as for our render boxes, and file servers”, says Hammerhead Visual Effects Supervisor Thomas Dadras. “I feel that Linux is the best possible environment for visual-effects production because it's so incredibly customizable and scalable. We utilize a full spectrum of in-house scripts, aliases and environment variables that enable artists to easily navigate the file systems for the many shows that we have in-house at any given time.”

Hammerhead uses Maya with RenderMan and Mental Ray for rendering, Shake and Nuke for 2-D compositing and rotoscoping, Photoshop for texture painting and matte painting, and SynthEyes for 3-D tracking. They've internally developed software for 2-D and 3-D tracking and rotoscoping.

“The company size fluctuates between ten to 25 people depending on the amount of work”, says Dadras. “We currently have 17 people. We have nine artist desktop-Linux workstations, all with dual monitors. The capacity of our Isilon server is 17TB. We also have an older SGI file server, about 5TB in size. We currently have 22 render blades on our renderfarm.”

“All our workstations and render nodes are running on CentOS 5”, says Hammerhead Systems Administrator Fatima Mojaddidy. Hammerhead has eight Macs that are used by producers and coordinators for running software such as Filemaker. A few of the Macs also are used in production with Photoshop and SynthEyes.

“Hydraulx stepped in right near the end”, says Okun. “They did the most amazing job of creating an army out of eight jeeps and 50 people. They were the only other people on the show to deal with any particle systems stuff.”

“All our workstations, our entire facility is now Linux”, says Hydraulx Visual Effects Supervisor Colin Strause. “We use Inferno and Flame, Shake, Maya, Photoshop, a little bit of After Effects, Combustion, Synflex for cloth simulations, Real Flow for fluid stuff and Massive. Everything after that is our own custom tools. We use GIMP for doing mid-level painting stuff—quick texture stuff. We've gone dual-boot on most of our Linux machines, so modelers and texture modelers can run Z-brush and Photoshop.”

“We have more than 500TB on the SAN network”, says Strause. “We have a Think Logical KVM switch, based on fibre, that will route your monitor, keyboard, mouse and tablet. You can take any machine in the building—our 25 Inferno stations or three big Final Cut Bays—and route it to any other machine in the building or up into the screening room.” (The screening room has a 23'-wide screen.)

“Our sequence takes place where the Swarm escapes from a missile silo where they were storing Gort”, says Strause. “The US military has hundreds of tanks and soldiers and missile launchers there in case something bad happens. The Swarm takes out the whole army. We were able to rent a handful of vehicles...some M-1 Abrams, some Bradley Fighting Vehicles, a bunch of Hummers with 50-caliber machine guns on the top and troop transport trucks.”

“We had only six to seven weeks to do the entire sequence”, says Strause. “Normally, you'd have three or four months. The other problem we had was matching all the Swarm dynamics that Weta did. Each company has such a unique pipeline, there's very little we can share. We looked at the trailer from Apple.com to figure it out and reverse-engineer their Swarm effects to create them from scratch for our shot.”

“With all the fires in Los Angeles, we couldn't shoot the weapons”, says Strause. “So for all the weapons you see firing, we had to add CG shell casings, and we created all the tracers and muzzle flashes with fluid simulations.”

“When a 60-ton tank shoots, it's going to shake the ground, so all the dust comes into the air”, says Strause. “When the tanks fire, we have all the correct dynamics, such as the heavy tank tread jiggling on the suspension. We went through YouTube, which is great, and found all these videos that guys had taken in Iraq of their tanks shooting. It was an amazing reference.”

“On set, we have a Sphere-On camera that lets you take 360-degree HDRI images”, says Strause. “We use these super-high dynamic images for photometric lighting, trying to re-create how the real light behaves in the real world in our digital environment. When we have a real tank and a CG tank right next to it, we have to use a much fancier technique to make it all look photo-real.”

Hydraulx photographed the vehicles at a desert location in Los Angeles, then modeled everything in Maya. Camera tracking uses Linux Boujou software, brought into Mental Ray for lighting and shading.

“We use digital crowd simulation software called Massive”, says Strause. “We've written some custom tools that let us get the stuff into Maya so we can render it in our Mental Ray pipeline. We have soldiers with guns and they're running. The soldiers avoid the moving vehicles automatically. It's all done with this neural network.”

“We have a custom version of Piranha here that we use for all our dailies”, says Strause. “We have it on every single Linux machine. We have an elaborate database, based on MySQL, that's our shot management and render manager. We can dynamically build edits. We can take an EDL of an off-line, and whenever people mark a new daily that they want to look at in the cut, they can hit View and Cut, and it will dynamically build off an XML file all the different QuickTimes, load Piranha and dynamically build the cut. We use Shake to build the QuickTimes as a job on our Linux renderfarm.”

“Linux is the OS of choice for the film industry”, says Autodesk Television Industry Manager Bruno Sargeant. “Linux leverages the processing power of current workstations and allows Flame and Inferno to reach performance previously obtainable only with supercomputers like SGI.”

Even more important than Linux are the artists using Linux. “Computers are machines, and they're no different from a paintbrush”, says Okun. “It's the artist running the computer who makes the difference.”