In a world of Web 2.0 applications, AJAX applications and content management systems with countless plugins, you might think the humble Web site is a thing of the past. Not true. But, when working with these sites, we turn to the same tools over and over again. Time for something a little unusual, non?

I thought you said this Web site was basically a single page, François, and yet you've been at it for hours. Are you having trouble tuning in to those creative waves? Oh, I see, you haven't even started the page. Still trying to set up a PHP content management system, looking for plugins and trying out themes? Seems like a lot of work for a one-page site. That house your Aunt Guylaine is trying to sell will have sold itself before you get her page up on our site. Now, now, François, I'm not trying to be mean. I'm simply suggesting that you might be working a little too hard, and it is getting late. Our guests are already starting to arrive, mon ami. Look sharp.

Good evening, everyone, and welcome to Chez Marcel, where fine wine is paired with delectable open-source software. Please, sit and make yourselves comfortable. Tonight's wine is a Sella & Mosca Cannonau Sardegna Riserva 2005, a rather intense Italian red that certainly will capture your attention. François, please head to the wine cellar and bring up a couple cases.

When it comes to HTML and site creation tools, there's comfort in the familiar. KDE users create with Quanta Plus, and GNOME users code with Bluefish. Yet, plenty of other tools exist; some you may never have heard of. Tonight, I'd like to introduce you to a few. Of course, you don't always need to create a Web page. All you need is a Web version of something you already have. For instance, simple tools are available designed specifically to convert one or another document format into HTML. Suppose you wanted to show off your rather sweet Perl script in HTML format, with syntax highlighting. That might take some pretty tedious HTML coding in an editor. There is an easier way.

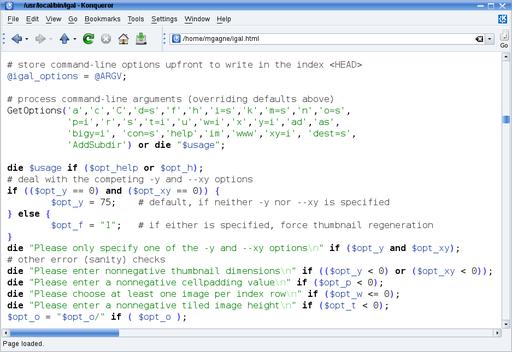

The faithful re-creation of code can be tough, especially with all those angle brackets, ampersands and other special characters that permeate many languages. For that, we have code2html, a rather clever little program that takes your code and turns it into great-looking HTML (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Perl script is converted to clean, easy-to-read HTML, courtesy of code2html. Extra points if you can identify the script.

The basic form of the command is:

code2html your_code > somefile.html

It certainly is possible that code2html won't be able to figure out what kind of code you are giving it. These are called modes in the program's notes, and you can display all the modes by calling code2html -m. Let's assume that the program couldn't make out a particular shell script:

code2html -o html-dark -l shellscript ↪/etc/rc.d/rc.local > ~/rc.html

Of course, I did add a couple additional flags. From the -m output, I found that the mode for a shell script was shellscript, which I passed using the -l flag. The -o flag tells the program to produce a dark background HTML page as opposed to the default white.

There are similar programs to generate HTML code from a variety of sources. Some operate locally to generate static pages, and others can act as CGI scripts and produce dynamic text (like man2html, for example).

What about the humble Microsoft Word, doomed forever to live in a proprietary format? Sure, you could find people with a copy of Microsoft Office and have them save the document as HTML, but why go through all that trouble? One very useful program I've used in the past is called wv. More accurately, Dom Lachowicz's wv is more of a collection of tools, including a library for creating filters within other programs. Some of these programs convert Word documents (2000, 97, 95 and others) into PDF (wvPDF), plain text (wvtext) and, yes, HTML (wvHtml), to name just a few. The real plus of using something like wvHtml is that you can batch-convert a whole collection of documents via a shell script.

To convert your .doc format file to HTML, use the following command:

wvHtml filename.doc newfile.html

If there are embedded images, they will be extracted with links added to the HTML file.

Eventually, however, you may need to do a little HTML coding yourself. Although it's not difficult to learn, basic HTML does require you to follow that particular language's syntax as you mark up your document for presentation. Even if you do know HTML, most people don't want to type out every tag and attribute manually. That's why we have HTML editors—to make that tedious work somewhat less tedious. In keeping with my theme of obscure, largely unknown Web creation tools, allow me to introduce a few HTML editors you likely have never heard of.

The first is HTMLpage, a simple HTML editor written in Python—and, I do mean simple. Regular visitors to this restaurant will know that I occasionally cover things for reasons that include fun as well as education. Given that this editor is basically a Python program, with plain-text code easily viewed and edited, it's also a great little program for learning and tweaking a little Python. Nevertheless, this oh-so-simple editor has some handy features, such as automatic table generation and conversion of links as well as basic text to HTML. There's a color widget for selecting and inserting color codes. The editor even supports drag and drop of page elements, such as graphics, directly into the editing window—all this in a few hundred lines of Python code.

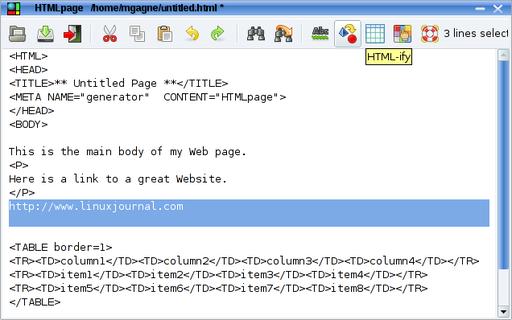

To use HTMLpage, simply extract the package into a folder of your choosing and execute the HTMLpage.py file from there. An editing window appears with the opening and closing HTML tags automatically inserted. From there, you can enter your text in between the body tags. Some things are pretty cool for such a simple program. For instance, enter your text, select it, and click the HTML-ify button. Paragraph and line breaks are taken care of automatically. Select a link (Figure 2), click that same button and the proper tags are inserted.

Figure 2. HTMLpage, though modest in design, has some interesting automatic features, like HTML-ify and Table-ify.

Want to create a table? Simply enter your text separated by tabs. On the second (and third and fourth) line, do the same until you have all your data. Select it, and then click the Table-ify button. Your information is inserted into a table automatically. When you click the HTML-ify button, just as when you click the Table-ify button, a little magic takes place beneath the surface. The result looks like what is shown in Figure 3.

Of course, if you are going to create something of any complexity, you will need something a little more interesting than HTMLpage. So, let's look at the second HTML editor you've probably never heard of.

While my faithful waiter refills your glasses, perhaps what you really need for that simple Web site or page is a spot of TEA.

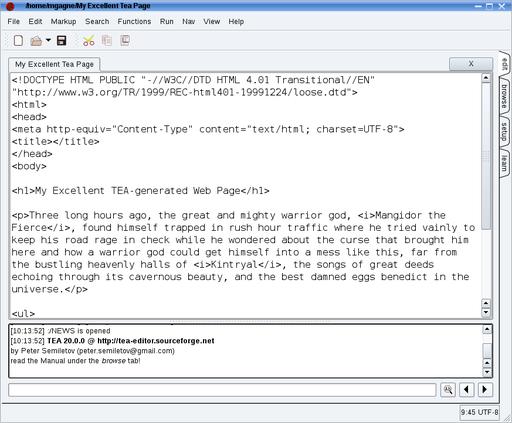

Peter Semiletov's TEA is a light, but full-featured HTML editor written in Qt (Figure 4). It's small, fast and contains a surprising number of features, including some you won't find in the larger, shinier Web site design tools. Aside from the obvious HTML tag edits, TEA has a tabbed layout, template and scripting support (Python, Perl, Ruby and so on), Bookmarks, syntax highlighting, drag and drop into the editing window (such as for images), Wikipedia editing and a whole lot more. There's even a Morse code translator—seriously.

Figure 4. The TEA HTML editor is available in both GTK and Qt. Active development, however, is Qt-only.

To try out the latest-and-greatest TEA, you'll likely have to build it from source (although some packages are available on the site), but that's relatively easy. Extract the source into a folder of your choice, and type qmake from inside that folder, followed by make install. The result is a single executable called tea. A slightly older version of TEA exists called teagtk (Peter recently shifted development from GTK to Qt). Although it's not as up to date, it should be in many repositories, just waiting to be downloaded.

Along the right-hand side of TEA's editing window, you'll see four tabs. These give you access to the editing window (which is itself multitabbed, one for each open document), TEA's built-in file browser, the setup page and, finally, a manual labeled learn. Below the main window, there's a scrolling status window that displays your most recent action. The file browser makes it easy to insert bookmarks anywhere inside your directory tree for quick access. TEA also has a special quick-access file called Crapbook (accessible under the File menu) into which you can scribble quick notes regarding your current project.

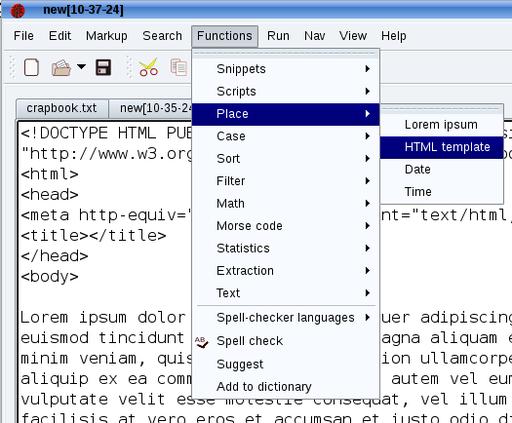

The best place to start, after clicking the New button, is in the function menu. While you can create and store templates to get you started on a project or page, clicking Function, then Place from the menu bar lets you insert a basic HTML template to start your document (Figure 5). Notice as well that all the menus are tear-off—there's a dashed line above each one. Simply click the dashed line and drag the menu to your desktop. You might want to do this with the Markup menu for basic HTML tagging.

Figure 5. TEA's menus are all tear-off. Simply click on the dashed line at the top of a menu and drag it to your desktop. And, yes, that says Morse code.

Let's move on to another editor you've probably never heard of. Screem, written by David Knight, is a great site creation tool written for the GNOME desktop environment (Figure 6). You can, of course, run it under KDE, as I am doing at this moment. If the name seems a bit frightening, cast your worries aside. Screem is an acronym for Site CReation and Editing Environment, and in that respect, it is aptly named. Some of Screem's features include a number of wizards to insert special characters (entities), generate a form, create a table or provide you with an easy way to select color.

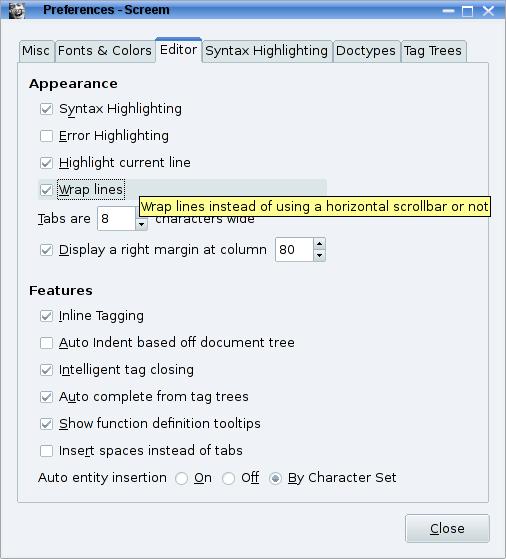

Before you get going on that first Web site, I am going to direct you to the Preferences dialog for a quick change of one of the default settings. Click Edit, then select Preferences. A six-tabbed window appears from which you can modify the default operation of much of the Screem's interface and features. There is one setting that I recommend you change right away and that's word wrap. Click the Editor tab and look for the check box labeled Wrap lines (Figure 7). Make sure it's checked on, and then click the Close button.

Figure 7. I'm guessing you'll want to make sure word wrap is turned on in the editor's Preferences dialog.

You can, if you want, take some time here to familiarize yourself with the other settings. Before I move on, however, let me direct you to one more that may interest you. Under the Misc tab, there is a timed backup feature (set at ten minutes by default) that you might want to activate. My personal favorite keyboard combination is Ctrl-S (used in most editors), and I tend to press it every couple minutes whether I need to or not. The autosave feature can take care of that habit.

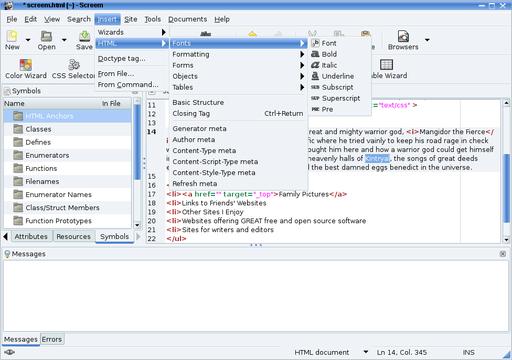

The edit window, where you type your text, is that big empty space on the left. When editing a page (Figure 8), you highlight text, click Insert, and then select your HTML markup from the submenu. Other markup elements, such as a link to another Web site, are best done using the wizards. These are on the second toolbar, but also under the same Insert menu.

Figure 8. The vast majority of Screem's functions and markup are found in the menus. The toolbars are reserved for core tools and Wizards.

On the right, there is a multitabbed sidebar. The tabs access a built-in file manager, a tag tree from which you can jump to any tag in any part of the document quickly, an attributes view that further defines all tags and their attributes, and more.

As you may have noticed, mes amis, the clock is telling us that closing time is upon us. While my faithful waiter refills your glasses a final time, remember this. The free and open-source software landscape is extremely rich with countless projects and programs available for your downloading pleasure. The easy path is certainly the one that installs the most popular programs, such as Quanta, the KDE HTML editor, or Bluefish, the GNOME favorite. Yet, there are many other projects, and as with a bottle of wine, it can be fun and educational to try those you've never encountered before. You even may discover a new favorite. Please, mes amis, raise your glasses and let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé! Bon appétit!