When was the last time you heard someone mention the browser wars? Most pundits love to point out that Internet Explorer's only real competition is Mozilla Firefox. One or two will give Opera a nod. But, what about the underdogs of the browser world?

Speed of lightning, power of thunder? What is this I hear? Mon Dieu, François! How on earth did you find that old Underdog clip? Ah, of course—YouTube. I am surprised, mon ami that you even know about this old cartoon—one, I confess, I enjoyed a great deal in my youth. Quoi? You don't know it? You were just doing some research for the issue's theme, underdogs? To be honest, I'm not exactly sure what our editors meant, but I don't think rescuing Sweet Polly Purebred from the evil Simon Bar Sinister was what they had in mind. Underdogs, François, refer to people (or animals or things) who are disadvantaged in some way. They may be smaller and not quite as strong as their opponent, so that in a contest or fight, they are expected to lose. People love to see the underdog win. But enough of this, François. Our guests are arriving as we speak.

Welcome once again, mes amis, to Chez Marcel, where fine wine is a naturally perfect match for fine Linux and open-source software. Please, take your seats and make yourselves comfortable while my faithful waiter attends to the wine. François, please head down to the cellar and bring back that 2006 Torbreck Barossa Valley Woodcutter's Shiraz we were, uhm, submitting to quality control earlier today.

Before you arrived, François and I were discussing the meaning of the word underdog. Cartoon characters aside, in the desktop Web browser world, you will find some true underdogs. I'm not talking about Firefox, and I'm sure most people no longer see Firefox as an underdog when compared to the Redmond OS's flagship browser. Instead, I want to show you some Web browsers worthy of the underdog label that you may well want to consider using. Despite not being as feature-rich as the heavyweights, these lightweight browsers have small memory footprints, make few demands on system resources and are, in many cases, as fast as lightning. Let me start with a text-only browser that, strangely enough, does graphics.

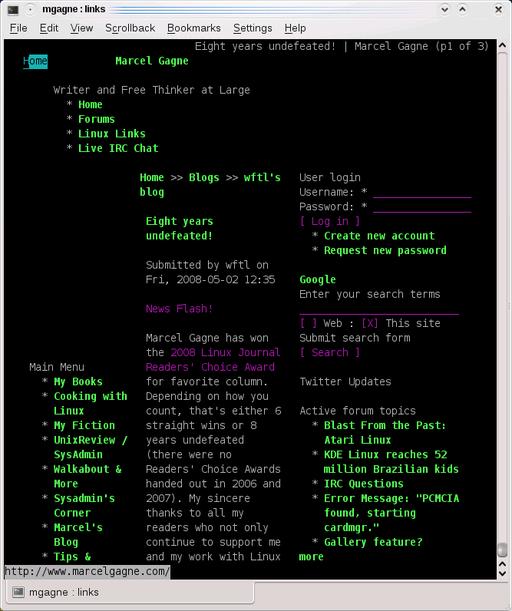

Links, created by Mikulas Patocka, is a text-only Web browser that is surprisingly rich in features (Figure 1). It can display tables and frames, and it supports colors, clickable links, SSL pages, background downloads and more. Sure, it works in text, but you have never seen pages load as quickly as you will when you decide to view the World Wide Web the way many of us first saw it—sans pictures. People doing research who want uncluttered information need to put away their graphical browsers and fire up Links. The effect of seeing only what you need, loaded in an instant, is a wonderful experience. Once you have used it, you always will make sure it is loaded on every Linux distribution you run.

Figure 1. Links is a perennial favorite for text-only Web browsing. When you can't get to a graphical desktop, nothing beats Links.

Links' popularity means you don't have to look far for it. Most distributions have it in their repositories. Source is, of course, available from links.sourceforge.net.

Although it's true that Links is a text browser, it does respond to mouse clicks. In a nongraphical environment, you navigate by using cursor keys, jump from link to link with the Tab key, page using the spacebar and follow a link by pressing Enter. In a text console running under a graphical desktop, things are a little different. When you see a link, simply click, and you will go there.

Did I say text-only? I may have been mistaken. Graphically speaking, Links isn't merely a text browser. An update to Links, available from Twibright labs at links.twibright.com, provides a graphical interface that works even if you aren't running a graphical desktop. That's right. This Links will work on your framebuffer console as well (Figure 2). Once again, you should have no trouble finding the package in your repositories. The difference is in the command. To run the text-only version of Links, use the command links. For a graphical version of Links, try links-graphic.

Ah, François, you have returned. Please pour for our guests. Enjoy, mes amis. This Shiraz has a wonderfully rich aroma, complexity and texture, along with black cherry draped over the signature Shiraz peppery flavor. Make sure you fill my glass as well, François.

Another alternative to the monster browsers of today, and one that is entirely graphical in nature, is Dillo. Created by Jorge Arellano Cid, Dillo's demands on your system are meager, and its performance is seriously snappy. It won't render complex pages or tables particularly well, but it does support image browsing and bookmarks. Dillo's small size, speed and tiny memory footprint can sometimes make up for its limited features. Figure 3 shows Dillo in action.

The current 0.8 branch of Dillo is no longer maintained, but it's still a mainstay in most major distributions' repositories. It's easy to find and install. A new version based on FLTK2 is where development is going at this stage. Those of you feeling a little brave and willing to do a little source code compiling are invited to download the development code from the site at www.dillo.org. The classic source is also available.

Finding a balance between the needs of offering a feature-rich browser while maintaining speed at a maximum and resources at a minimum is the driving force behind the final two items on tonight's menu.

Our next selection for tonight is Christian Dywan's Midori, a great little Web browser whose rendering engine uses WebKit instead of Gecko. For those who may not know, WebKit is an open-source rendering engine based on KHTML, the HTML rendering engine created by the fine people of the KDE Project. Midori (Figure 4) also features tabbed browsing, custom context menus, configurable interface, JavaScript plugins and, of course, peppy rendering, courtesy of WebKit.

Changes to Midori's interface and behavior are largely controlled via the Preferences dialog (Figure 5). Click Edit on the menu bar, and select Preferences. From there, you can set a default home page, change the look and feel (including default fonts), and more. You'll also find evidence of Midori's young age when you run into pages that don't yet allow edits.

Midori is, as I mentioned, a young browser. It's also a fascinating and promising project, and it's fast. Really fast. And, it's the only browser on my system to pass the Acid3 test (acid3.acidtests.org).

The final item on our menu is Hidetaka Iwai's Kazehakase, a graphical browser that uses the Mozilla Gecko rendering engine to display Web pages. As such, it doesn't lack for much when it comes to showing off Web sites as you expect to see them. Kazehakase, which means “Wind Doctor” is named after a short story by the Japanese author Sakaguchi Ango. This is a great little program that features tabbed browsing, customizable mouse gestures and keyboard shortcuts, RSS bookmarks and more (Figure 6).

Possibly the coolest thing about Kazehakase is its graded user interface. It's a great concept. By default, the user interface is kept as simple as possible, providing users with only the basics both in terms of menu options and configuration of system preferences. The user interface level (UI levels) can be set to beginner, medium or expert. At each level, you find additional hidden gems under the surface that let you fine-tune the browser. There are two ways to change the UI level. The first is by changing the preferences. To get to the system preferences, click Edit on the menu bar, then select Preference. The beginner UI preferences window appears with the main options to the right and a sidebar menu on the left (Figure 7).

Figure 7. On the left, you can see Kazehakase's basic (or beginner) preferences. To the right is the same dialog but in expert mode.

There are only four categories of simple changes here. If you change the UI level to expert, a much more complex and complete preferences menu appears, as shown on the right-hand side of Figure 7. If you choose, you also can toggle the UI level directly from the menu bar by clicking View and selecting your level of expertise from the UI level submenu (Figure 8).

Kazehakase isn't widely available in distribution repositories, so you may have to resort to the old extract-and-build five-step for that one. This is a great little browser and well worth checking out.

There you have it, mes amis, the underdogs of the browser world—some of them anyhow, as I am sure there are plenty more. Can any of them compete against the big guys? That depends on your needs and constraints. If fast as lightning trumps a bulked-up feature set, the underdogs win. The same is true on a small, underpowered machine. Researchers who are more interested in text may opt out of the graphical browsers entirely. Each underdog, you might say, can have its day.

Speaking of day, this one is nearly done, and the only browsing I intend to do after closing is in the wine cellar. Speaking of which, keep your glasses handy as François will happily refill them a final time. Raise your glasses, mes amis, and let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé! Bon appétit!