Look (and listen) in on the OLPC's laptop audio designs.

In January of this year, I received an XO laptop from the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) Project, thanks to a kindly recommendation from my friend Dr Richard Boulanger, professor of music synthesis at the Berklee College of Music. Rick knows that I maintain a private teaching studio and that many of my students are youngsters who would love to play with the XO. He also knows that I have a twin interest in Csound and Linux audio development, two rather significant aspects of the machine. Thus, this article focuses on my experiences so far with the XO's audio subsystem and its sound and music software. My students have had only brief exposure to the machine, but I conclude with some remarks concerning their interaction with the XO and its audio capabilities.

There's plenty of material on the Web that describes the XO in minute detail, so here I recap only the most salient features of the machine.

The XO laptop (Figure 1) is small and lightweight without feeling flimsy or poorly constructed, and the few mobile parts are connected firmly at their joints. The display swings up from the base and can be rotated 180 degrees left or right in its upright position. It also can be tilted slightly backward. The keyboard is a single rubber membrane, designed for kid-size fingers, but ham-handed adults like yours truly can plug in a USB keyboard if necessary. A two-button touchpanel replaces the mouse, though currently only one panel and one button are active. That's not a problem, because only the pointer control and an entry button are required to navigate the GUI.

I'm impressed by the thought that has gone into the design of the XO. At every level, I find consideration for the user's experience, from the design of its battery pack to the excellence of its display resolution. In fact, when I've shown the machine to friends, they've all especially admired the handle and wondered aloud why their laptops didn't include one.

On the software side, the XO is powered by a modified version of Fedora Core with a 2.6.22 Linux kernel. The GUI is the renowned Sugar, a Python-based graphic interface that is singularly unlike the typical Linux desktops with which I'm familiar, and the Linux command-line is easily available at any time.

The XO's CPU is a 433MHz AMD Geode LX-700. The laptop's multimedia capabilities are provided by the Geode CS5535/CS5536 companion chipset. According to the Wikipedia page on the Geode, the CS5535 is a “...Southbridge for Geode GX and Geode LX...[that] integrates four USB ports, one ATA-66 UDMA controller, one infrared communication port, one AC97 controller, one SMBUS controller, one LPC port, as well as GPIO, Power Management, and legacy functional blocks”. The processor's AC97 controller is of central importance to this article, along with the possibilities afforded by the USB support, so let's consider exactly what that AC97 is and what it does.

In 1997, Intel developed an audio codec to provide high-quality audio services for motherboards, modems and sound hardware. The AC97 defines a high-quality audio architecture with a sampling rate of up to 96kHz for stereo and 48kHz for multichannel digital audio recording and playback, with bit depths up to 20 bits. The AC97 became very popular with manufacturers and is found on most desktop machines, though it has been superseded recently by Intel's HDA (high-definition audio). The codec is divided into a digital controller and an analog stream handler, effectively combining the analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog converters in a single package (an appealing feature for hardware designers). By the way, Intel's use of the word codec here refers to the encoding/decoding of analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog streams, as distinct from binary compression/decompression codecs such as MP3, Ogg or WMA/WMV.

The AC97 implementation for the CS5535 comes from an integrated Analog Devices AD1888 chipset that provides up to six channels of digital or analog audio output. The AD1888 is notable also for its direct connection to the core CPU, a cost-saving factor that accords nicely with the XO's overall design. The XO also uses another Analog Devices chipset (the SSM2211) for audio amplification.

So much for audio on the inside. On the outside, we find an integrated microphone, two integrated speakers and jacks for stereo audio output (to headphones or other speakers) and for a monaural microphone-level input. The jacks are standard consumer-grade sound-card connectors that take 3.5mm mini-plugs, and I'm happy to report that connections to those jacks are firm and steady. The jack functions also are redefinable with the alsamixer utility, but I did not experiment with this feature. See the OLPC Wiki page on the XO's audio hardware for more information about redefining the audio I/O ports.

The XO also includes three USB ports. Obviously, these ports can be used to expand the machine's audio capabilities by adding a MIDI interface or a higher-quality digital audio interface.

My machine runs the ALSA sound system in version 1.0.14. Running dmesg reports that the ALSA device list consists of the CS5535 audio hardware at base address 0x1480 on IRQ5, and modinfo reports that the cs5535audio driver includes only one significant option, a workaround for certain faulty AC97 implementations.

Under normal circumstances, ALSA is completely transparent to the user. Activities (that is, the XO's programs) access the kernel sound services with no intervention from the user, and sound pours forth from the speakers. The expected ALSA utilities are all available from the command prompt, though only to the root user. Alsamixer correctly identifies the CS5535 as the sound card and the AD1888 as the audio chipset, and the range of mixer controls is impressive, particularly with regard to the surround sound capabilities of the AC97. Given this transparency, there isn't much else to add regarding ALSA on the XO. However, readers who want to know more details about the CS5535 audio driver should read the papers by Jaya Kumar, developer of the cs5535audio driver (see Resources for links to his presentations at the Linux Audio Conference 2007 and at FOSS/India 2006).

The XO is designed for the explorative mind. With regard to basic sound, the default system provides activities for simple audio recording and playback in various formats. However, the system's real audio attractions are found in the TamTam activities.

TamTam is a suite of four programs designed for exploring and experimenting with sound and music creation. At first glance, they may seem to be attractive toys, but I can verify that these applications are powerful enough to keep experienced musicians busy with their possibilities. The TamTam designers have created a unique blend of Python and Csound and presented the concoction to the user in an interface that completely conceals its technical foundations. The GUIs are easy to comprehend, and users need no knowledge of Csound or Python or even music to start composing, jamming and making their own sounds.

Alas, there isn't space in this article to describe each program in the suite fully, so I present each application briefly and advise interested readers to listen to the XO audio demos I've posted at linux-sound.org (see Resources).

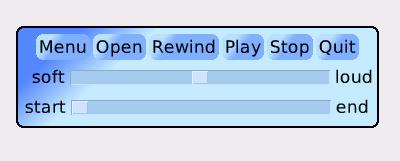

The TamTam Mini (Figure 2) is an introductory-level program for very young users. The Mini is essentially a preset-style synthesizer played with the computer's keyboard. Users select an instrument from the display, and then play it by pressing the keys Z through M (lower octave) and Q through I (higher octave). A drum set can be added to create a looping play-along beat (with the start/stop button), and further controls include sliders for master volume, tempo, beat complexity and number of beats per bar. Sliders also are included for balance (that is, panning) and a reverb effect. All controls are usable in real time, and users' jams can be recorded for later playback. Finally, in accord with the XO's design philosophy, Mini also supports collaborative play between multiple machines, with all players synchronized to a shared beat. TamTam's Mini may be simple in its operation, but it is a sophisticated learning tool that succeeds at being instructional and fun—a winning design for enticing children into learning more about music and sound.

The TamTam Jam (Figure 3) is the XO's main music performance activity. As with the Mini, users select sounds from the display and play them via the computer keyboard. A beatbox-style drum machine is available for accompaniment grooves, and a sequencer is provided for recording phrases played on the keyboard. Jam also is targeted at younger users, but it is a much more sophisticated program. Polyphonic playing is supported, and users have full control over the accompanying sequences and their instrumentation. A virtual band can be formed with a drum set and up to five instruments, and each instrument is coupled to a series of sequence loops selected from the Loops display. These loops can be added or deleted in real time, and right-clicking on the loop invokes its editor. The loop editor controls the number of beats within the loop and its “regularity” (a randomization control), and a mini-piano roll editor lets users redefine the notes and their order within the loop. It won't take long before users realize that Jam is a powerful MIDI sequencer that can make music in almost any style or degree of complexity.

TamTam's Edit (Figure 4) is a music composition/generation program that can be employed as a more-or-less conventional five-track MIDI sequencer or as a user-definable musical automaton. Beyond its transport controls, Edit's toolset differs between its two modes. Compose mode includes Select, Draw and Paint tools; volume and tempo sliders; and controls for recording from the computer keyboard and saving your work as an Ogg file. Generate mode includes only three tools, a Generate Tune toggle and dialogs for the music generation parameters and for other general properties of the sequence. The generation dialog has a cool interactive graphic interface for setting the conditions for each generated event's rhythm, pitch and duration. Pitch material can be defined further with selections from seven scales and four randomization modes, any of which can be defined in real time.

Playback can be limited to a single sequence to create a real-time loop composition environment. Sequences can be selected in noncontiguous order with a Ctrl-left-click, although playback is always from left to right. Hold and sweep with the same key combination selects multiple continuous sequences.

Edit is an impressive toolkit for serious music composition, whether in real time or off-line. I've worked with dozens of music generation programs in text-based and graphic interfaces, and few of them are as well designed as Edit. In software reviews, the word flexible is usually overworked jargon, but it applies neatly to Edit. The program supports a variety of approaches to music composition, from the strictly deterministic to the utterly aleatoric, and it presents itself with an interface that welcomes interactivity. Edit has its limits, but within those limits, it is one of the coolest music programs I've used to date.

The TamTam SynthLab (Figure 5) is a sound design laboratory for advanced students. According to the TamTam Wiki, the SynthLab is modeled on the famous Max/MSP, a graphic environment for music composition and multimedia development, but it reminds this reviewer of PatchWork, an ancient editor for Csound instruments. In SynthLab, as in the older program, icons representing synthesis primitives are wired together to create a patch—that is, a new sound. SynthLab provides modules for sound generation (FM, sample playback, granular synthesis), modulators (LFO, envelopes) and effects processors (delay, reverb, chorus) that can be wired together in arbitrary connections to create new sounds, all in real time, of course. These sounds can be played on the computer keyboard and/or saved to any of eight slots reserved for use in TamTam Mini.

The TamTam suite is a great achievement, particularly when considered in its hardware context. It certainly proves a point about efficient program design, and there were many times when I forgot that the TamTam software was doing its stuff on a machine with a 433MHz CPU. It also proves a few other points about leveraging the power of contemporary Csound and Python. Those languages have been developed for excellent real-time performance, a factor well exploited by the TamTam programs. Vast thanks and praise must go to Jean Piche, TamTam's master architect and to his crew of talented developers for coming up with this most fascinating, instructive and hugely fun group of activities and for giving it to the children of the world. (And, yes, that includes children of all ages.)

I knew that the XO was able to play media files in various formats, but at first I was mystified as to how to access such files. The Sugar interface doesn't provide a file manager a la Nautilus or Konqueror. Instead, the Journal activity lists all work done on the machine in a kind of diary. All saved work also is listed there, including recordings and other media files, and I needed only to double-click on an item to view or listen to it.

Players are invoked automatically for a selected file. On the base system, I had no trouble playing MP3, Ogg and WAV audio with the players in the eToys and Browser activities (Figure 6). I also played video files in AVI, MPG and Ogg formats, with the understanding that playback was not likely to be cinematic with a 433MHz CPU. However, videos made on the XO are recorded at 30 frames per second and played smoothly (in their original 640x480 resolution) when transferred to my more powerful desktop machines.

Figure 6. The eToys MP3 Player

Audio recording on the XO is done with the Recorder activity, a simple utility for capturing pictures, video and sound. After selecting the particular media task, a “ready to record” icon appears (an eye for video and lips for audio). Click the icon to start recording, and click it again to stop the process. The file is named and saved automatically, and it can be previewed directly from the Recorder.

I tested the audio recorder with the internal microphone and with an inexpensive external mic. To its credit, the internal mic recorded with less noise and a stronger signal. I've since decided to do all casual recording on the XO with its own microphone. Settings for the microphone input level (and all other audio channel levels) can be managed with alsamixer or any similar sound card mixer, but I found the default levels to be adequate under relatively calm acoustic conditions.

The XO's internal speakers are okay for basic purposes, but they will not provide high-fidelity sound. For a better audio experience, I suggest either good-quality headphones or a set of powered external speakers. Surround sound playback is supported by the XO's audio chipset, so you may want to attach a 5.1 system. Alas, I was unable to find technical specifications on the integrated speakers, but it's obvious on listening that bass response is almost nil, which gives the audio a thin and tinny sound. This is especially unfortunate with regard to the TamTam software—it simply sounds far better on external speakers.

Thanks to the pioneering work of Michael Gogins, Steven Yi and other developers, Csound now includes a number of Python-related opcodes. Python is rather ubiquitous in the XO's software structure, and Csound is the audio engine for the machine, so it's a wrap that the XO might be an excellent platform for experimentation with the world's most powerful music and sound programming language. Alas, I've run out of space to describe adequately the XO's Csound/Python potential in this article, but I can recommend interested readers to the OLPC Wiki page on Csound. A few pointers to relevant projects and activities can be found there, and further information can be discovered in the Csound mailing list and its archives. Jean Piche and Rick Boulanger are Csound gurus, so I have great expectations for working with the language on this machine. If TamTam is any indicator, the creative possibilities are truly impressive.

I loaned the machine to two students, both of whom had trouble figuring out how to save their work. They discovered how to use the Recorder and other activities with little difficulty, but the Save procedure was dark to them until I explained the Journal and its functions. Documentation is entirely Web-based, and the students said it was a hassle to switch between the Web browser and their current activity. Of course, once they learned how to use the Journal, all was well.

The only other problematic area for me was the wireless connectivity. Connections are hard to come by in my area, and I would have been happier with an Ethernet port. However, I understand the design consideration, and my USB-to-Ethernet adapter is already on order.

If you've been waiting to purchase one machine for yourself or thousands for children in the remoter parts of the globe, just do it. The XO is intended to spread happiness and joy throughout the world, but the project needs your help to achieve this lofty goal. See the OLPC Wiki for more information on how you can get on board.

So, do I like the XO? I love this machine, and I heartily recommend it to anyone anywhere. It squeezes more juice from a relatively low-powered CPU than I would have thought possible, the TamTam software's performance is nothing short of astonishing, and the fun factor scales right off the charts. The XO gets five stars for overall excellence, and if I had to choose a single word to describe the machine and the experience of using it, that word would be joyous.