This article provides insight for creating a full-fledged, web-based database application under Linux, using David Hughes' mSQL package and standard Unix tools.

Over the past few years, many companies have realized the benefits of using Linux to serve web content to the masses. The power of a freely available, feature-laden 32-bit operating system, coupled with a vast number of utilities and development tools, provides a cost-effective solution for implementing enterprise and publicly-available information servers.

While many organizations have championed Linux as a web server, few have taken advantage of perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of the Web: dynamic content generation and delivery. Think about it. Of all the web sites you visit on a regular basis, how many of them have static content? Not many. Many us go to Yahoo! each day to see “What's New on the Internet”. Many cruise over to catch the news on CNN throughout the day. These sites have dynamic content. If the listings on Yahoo! didn't change every day, how many of us would go back after the first visit?

To provide dynamic content to your cyberguests, you can use a variety of tools and methods. One of the more popular approaches is to integrate data repositories with the Web. Creating web-based applications that integrate with existing database pools seems to be the rage this year. This paradigm has led to some amazing third-party products such as Bluestone Software's Sapphire/Web (http://www.bluestone.com/) and Haht Software's HahtSite (http://www.haht.com/). These products provide full development environments for designing, creating and deploying web-based applications. Unfortunately, the majority of these products are not yet available for Linux (iBSC options ignored for the moment). However, there is an alternative.

You can retrofit a Linux-based web server to provide access to enterprise data in a very cost-effective manner. Third-party packages typically have an integrated development environment (IDE) to provide for seamless, somewhat painless development. This can be easily replaced by your favorite text/HTML editor. Third-party packages typically interface nicely with expensive, proprietary database platforms such as Oracle, Sybase and Informix. These database systems cost thousands of dollars, and generally require a seasoned database administrator (DBA) to operate efficiently. In our Linux model, we will employ David Hughes' mSQL engine, which costs a whopping $170 USD, and is a breeze to use. To fully implement such an approach, expect to spend no less than $10,000 on the software alone. The Linux/mSQL approach (including the cost of a Linux CD-ROM distribution, the mSQL engine and coffee) should cost around $250. Senior management has always had a love affair with saving money—show them the numbers. It sells itself, folks.

In this article, the following assumptions are made:

You have a working, fully installed Linux server.

You have a functional HTTP server running (NCSA, CERN, Apache, etc.).

You have installed either BASH, pdksh or ksh93.

You have the standard Unix tools in place (awk, sed, Perl, etc.).

The first item you need is the mSQL (mini Structured Query Language) engine itself. The mSQL package implements a relatively fast, lightweight database engine that uses a subset of the ANSI SQL standard to perform its operations. As of this writing, the current stable release is version 1.0.16, although the long awaited v2.0 release has been promised soon. It can be obtained via ftp at ftp://bond.edu.au/pub/Minerva/msql/. The official home of mSQL is at http://Hughes.com.au/.

Next, you need the w3-msql package, also written and distributed by David Hughes. This package provides the CGI (Common Gateway Interface) interface to the databases managed by mSQL. As of this writing, the current version of w3-msql is version 1.0, although 2.0 is in the works. It is available via ftp at ftp://bond.edu.au/pub/Minerva/w3-msql/.

Finally, the example scripts presented in this article are available via ftp at ftp://www.dcicorp.com/pub/unix/msqlweb/. Unless you are a typing enthusiast and are already familiar with mSQL, I recommend you snag the examples.

Once you have obtained the distribution archive, move it to either a scratch directory or the base of your normal source tree. You can extract the package as follows:

gzip -d msql-1.0.16.tar.gz tar xf msql-1.0.16.tar

To prepare for compilation, switch to the ./msql-1.0.16 directory and execute the following commands:

make target cd targets/Linux* ./setupYou will be asked the following questions pertaining to the actual build of the package. Here are a few notes to guide you:

Top of install tree? While mSQL can be installed virtually anywhere on your system, you should use the default path, /usr/local/Minerva. It makes installing third-party add-ons easier.

Will this installation be running as root? This question is concerned primarily with the TCP port mSQL uses for network communication. If your distribution is running as root, the default TCP port is 1112; otherwise port 4333 is used. You can tailor these defaults in the ./common/site.h header file. Also, take a look at the mSQL FAQ, available at the mSQL web site, which describes a number of other scenarios this setting affects.

Directory for PID file? Where do you keep your PID files? The default is /var/adm, which is fine for most folks.

At this point, the script will finish its tailoring process. Before you actually compile the package, you can perform several customizations by editing a few of the source files. The first, ./common/site.h, contains such gems as selecting the German language over English for error reporting. Give it a quick glance and make sure you are comfortable with the settings. Another possible modification lies in the ./msql/msql_priv.h file. I like to bolster my database limits a bit. At the top of this file are several values you can alter to suit your needs, including the maximum number of fields returned in a query, maximum number of network connections allowed, and the maximum length for field and table names. Feel free to modify these as you see fit. For the non-adventurous, the defaults should suffice.

To compile the package, simply execute the following command from the base source directory (./targets/Linux*):

make all

Compilation on a Pentium-class machine generally takes a little over a minute. If there are no compiler errors, you can install the package by executing the following command:

make installThe system is installed in /usr/local/Minerva (or whatever you set the install directory to when you ran setup).

Compiling and installing the w3-msql utility is much simpler. After you obtain the distribution archive, extract it into your source or scratch directory as follows:

gzip -d w3-msql-1.0.tar.gz tar xf w3-msql-1.0.tar

Change into the w3-msql-1.0 directory, and remove the -lsocket -lnls assignment to the make variable LIBS. Linux does not require these libraries to be linked into the application. Run make, and you are in business. If the build was successful, simply copy the w3-msql binary image over to your web server's cgi-bin directory.

The mSQL server process needs to be invoked during your machine's startup procedure. Place a line similar to the following in your /etc/rc.d/rc.local file:

/usr/local/Minerva/bin/msqld&

For testing purposes, and to save you a reboot, execute the above command from the shell prompt. This gets the server process up and running, ready to handle your database requests.

To make sure your mSQL server has been installed properly, several test scripts are supplied with the mSQL distribution archive. Finally, make sure you take the time to look over the mSQL documentation.

As part of this article, a fully functional web-based database application is presented in its entirety. The purpose is to provide a framework for your own web endeavors, as well as to show off the ease with which you can construct these types of applications using standard Unix tools.

Our example focuses on the creation and interaction of a database to contain concert listings that contains several items of information for each concert. First, we concentrate on populating the database with a series of concert listings, then build some web-based queries.

Before we create the database schema itself, we need to determine the functional elements of the application. What information needs to be stored in the database? What types of queries will be offered to our web guests? Do we need the ability to allow additional concert entries to be added through the Web?

Our database stores the concert date, opening act, headlining act, location and ticket price. For now, we concentrate on simple queries such as looking up concerts by band name and location. We also assume the “add” page is either protected by HTTPD authentication or made available through an Intranet.

The following is the mSQL schema we used to create the concerts database:

create table notices (

show_date char(10),

headliner char(30),

opening_act char(30),

location char(30),

ticket_price char(10)

)

To create the sample database and load it with initial data, execute the mkconcerts script located in the examples archive. For those of you who don't have ftp access, the data are shown in Listing 1.

To verify that the data have been loaded properly, execute the mkreport script (see Listing 2. mkreport Script), which is also in the examples archive. This script simply dumps the contents of the database into a formatted table, called concert.listings, shown in Listing 3.concert.listings File

Now that the database is created and populated with test data, it's time to begin constructing HTML pages that interact with the database. (Keep in mind that this article is intended to supplement but not replace the documentation that ships with mSQL and w3-msql.)

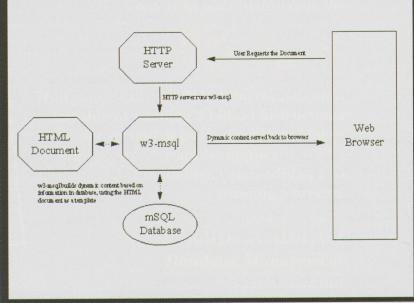

w3-msql acts as an HTML “preprocesser” of sorts. It takes a standard HTML document and performs database actions based on embedded mSQL primitives as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Process Flow

As a first example, consider the HTML document named ex1.html, shown in Listing 4. HTML Document with Embedded mSQL Commands, which demonstrates a simple link to a document containing embedded mSQL commands.

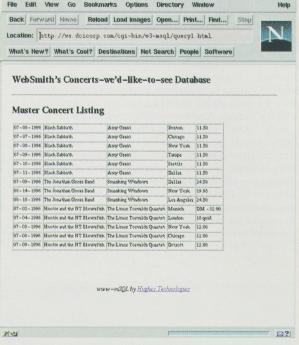

Note the calling procedure. The document name is placed immediately after the invocation to w3-msql (PATH_INFO). w3-msql takes this document, looks for any embedded mSQL commands and sends the appropriate output to the client. In this case, we are requesting the query1.html document, which contains the HTML shown in Listing 5. HTML Document. When selected, the output of the w3-msql link is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Output of ex1.html/query1.html

While the previous example is rudimentary, it demonstrates the ease of presenting information from an mSQL database. Let's continue with this example by expanding our queries. One nice feature to implement is the ability to produce a listing sorted by a specific field. Consider the following rewrite of our ex1.html file, which adds several hypertext links, each sorted on a different field. The file, called ex2.html, is shown in Listing 6.

Note the addition of the ?sortby=?????? parameters. We create new variables, make an initial assignment, and pass that, along with the document name (now called query2.html), to w3-msql. We use the sortby variable to contain a field name on which we wish to sort the listing.

Now that we have coded the skeleton for the front end, what changes are needed to the actual query template? Consider the rewrite of query.html, now appropriately called query2.html, shown in Listing 7.

Listing 7. HTML Document query2.html

The only major change is in the mSQL select statement. We added the standard ANSI SQL order by clause, passing along the content of our new sortby variable. In addition, note the use of the mSQL print command to display the sort field name in the header above the table. A sortby location displays the HTML table shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Concert Data Sorted by Location

To finish our simple query example let's revisit the concept of searching by location. Let's allow the user to input a city name manually, and pass it along to w3-msql for querying. Consider the simple HTML document, called ex3.html, shown in Listing 8. It provides an input field in a form, linked to w3-msql as the form processor.

Listing 8. HTML Document ex3.html

The query3.html document, which handles the actual query-by-city is shown in Listing 9. Note the change in the mSQL select statement. We use the contents of the form field in the ex3.html document as the value of a where-like SQL clause.

Listing 9. HTML Document query3.html

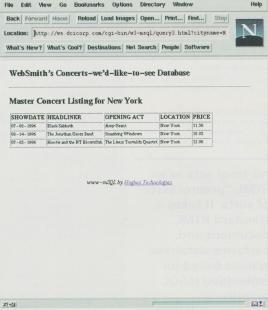

To test this form, enter New York as the city name—Figure 4 shows the output.

Figure 4. Form-based Query Results

That about sums it up for performing simple queries to a mSQL database. Try experimenting with different tables and interface designs. Try using frames. Place a search form in one frame and the query results in another. The possibilities are endless with the Linux/mSQL approach.