Take your application out for spin with Accerciser, and see whether it's accessible.

You might think you need to be familiar with assistive technologies like the Orca screen reader to determine whether your application is accessible. The truth is that with just a couple simple rules and an open-source tool called Accerciser, the task at hand is fairly simple.

Before you start diagnosing your application with specialized tools like Accerciser, you should ask yourself a few straightforward questions about your application.

1) Does my application's functionality depend on colors, icons or audible feedback?

Sometimes an application uses a certain color, graphical icon or sound as an indicator of its status or as a notification for users. A simple example is a battery-status panel applet; the applet warns users that their laptop battery is low by changing the battery icon from green to red. Of course, if users are blind, neither the green nor the red icon will be helpful if a textual description is not provided. Color-blind users also will be unable to decrypt such a status indicator. As another example, a calendar application may have an audible alert with no visual indication when an appointment time is approaching. This, of course, would be a useless feature to people who are hard of hearing, or even to those who simply have their audio muted.

Such applications should offer alternative means of access to their features. Maybe a tooltip or label for the CPU monitor? Maybe an optional alert pop-up for the calendar program? These kinds of changes might not always be the perfect and most elegant solution, but remember, the line separating accessibility from usability is blurry and often nonexistent. The colored dot on the CPU monitor might look nice by itself, but give users options as to how they can use your application.

2) Can users adjust the font size and interface color scheme in my application?

If your application utilizes a standard widget library like GTK+, the answer to the question above is yes. GTK+ is fully themeable. In fact, most Linux distributions provide a set of large-print and high-contrast themes to enable greater accessibility.

The question above should be examined seriously by ambitious developers who create a custom widget that is not provided by the toolkit. A good way to test a new widget is by applying an inverted high-contrast widget theme. Does the interface show up well? Is it conforming to the user-set widget theme?

Just like themes, most modern desktop environments provide a central place where the default font style and size can be defined. If your application is rendering text through the standard code path, chances are high that the font style and size the user defined globally will be applied to your application. But, what if your application explicitly defines font style and size? Or, maybe your application does specialized text rendering? In these cases, it is important to give the option for tweaking the font in your application.

3) Can my application be used without a pointer device?

Many conditions inhibit the use of pointer devices, for example, muscle weakness, hand tremors, involuntary movement or difficulty in seeing the mouse pointer on the screen due to visual impairment. For these reasons, it is important to enable nonpointer interaction with your application's features. This, of course, is easy to test. Disconnect your mouse and hide it where you won't find it. Use your application to ensure that you could reach and use all of your program's functionality. This also is a good time to think about useful keyboard shortcuts and mnemonics. Users will thank you when you make certain functions easy to reach without strenuous interface navigation.

4) Does the focus order in my application make sense?

Because you can't assume that users will be using a mouse, tabbing focus order should be considered. Remember the last time you bought something on-line? Most users fill out the order form by tabbing to the fields and typing: first name, tab, last name, tab, street address, tab and so forth. Wouldn't it be aggravating if, after you tabbed out of the name field, the Submit button got focus? Although sighted users might find this to be an inconvenience, screen-reader users will get a larger dose of confusion, because the work flow, when using a screen reader, is dictated by the focus order.

The visual appearance of your application does not need to change in order for it to have a good tabbing order. GTK+'s API has functions for defining the focus order of a parent widget's children.

After you have asked yourself all of the above questions and provided satisfactory answers, it's time to see whether your application provides the proper instrumentation to assistive technologies, such as Orca. The functionality and state of your application are provided to the assistive technology through a CORBA-based framework called AT-SPI (Assistive Technology Service Provider Interface). From your application's side, the communication with assistive technologies is done with a library called ATK (Accessibility Toolkit), which allows you to create Accessible objects that are synonymous with your graphical widgets.

In most instances, when you use GTK+, the accessibility internals should not concern you, because GTK+ has a module called GAIL (GNOME Accessibility Implementation Library) that does most of the heavy lifting for you. GAIL takes all of GTK+'s stock widgets and provides proper Accessible objects for them using ATK.

Accerciser gives a top-down view of what your application is providing regarding assistive technologies. It does this by tapping in to the same interface that an assistive technology would use, AT-SPI. Accerciser fits the needs of many different audiences. It is a tool used by assistive technology developers to see what AT-SPI is providing their applications, and it is used by automated UI test developers by exposing the different methods and events that could be expected from their target application when they author test scripts. And, in our case, it allows user interface developers to ensure that their application is providing all of its functionality through AT-SPI. In short, it allows us to exercise the accessibility of our application.

You can obtain Accerciser by downloading it from Accerciser's Web site, or check your distribution to see if it is already packaged.

Accerciser consists of a fairly small core. Most of Accerciser's features are in its bundled plugins. Accerciser's main window has three major areas: a tree view of the entire desktop accessible hierarchy as exposed by AT-SPI's registry, and two tabbed plugin areas. Accerciser's plugins can be toggled and rearranged simply by dragging the plugin tabs: drag a tab to another plugin area to move the plugin to that view, or drag the tab over the desktop to create a new window with a plugin view in it.

An easy way of diagnosing our application is with the Interface Viewer plugin. Accessible objects could expose a wide range of functionality by providing more than one interface type simultaneously.

The interface viewer plugin allows users to explore the functions a selected Accessible object provides. We use this plugin below to examine a fictional application.

So far, it seems that we get everything we need for our application's accessibility for free just by choosing GTK+, right? We have theme compliance, we have keyboard navigation, we even have AT-SPI support. So, where could we be falling short of full accessibility?

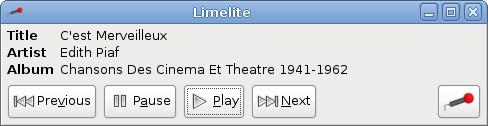

First, let's create a fantasy application called Limelite. Limelite is a simple song-playing program with one killer feature: by pressing a toggle button in the GUI, the vocals are magically removed from the sound output, and the user, for a few minutes, could be a rock star.

Limelite's main window is divided in two. The top shows data about the currently playing song, and the bottom has common media controls (play, pause, next and so on) and a toggle button that enables or disables karaoke mode.

Figure 3. Limelite Screenshot

To examine Limelite through Accerciser, all we need to do is run both programs. Limelite's top accessible node will appear in Accerciser's tree view. As we traverse down through this node's descendants and select child nodes, we will get a flashing rectangle around the equivalent widget of the selected accessible node. When a node is selected, the plugins will update and show information about the currently selected Accessible object.

When you spend time designing an application's interface in a visual manner, issues like proper labeling often are overlooked. We use Accerciser to find such instances quickly.

Accerciser comes with a plugin called Quick Select. Put the pointer over the widget you want to examine, say the Play button, and press Ctrl-Alt-/, the button is highlighted, and Accerciser's tree view shows the Play push button as selected. Because the Accessible's name is Play, we can be certain that an assistive technology will not have trouble conveying the function of that button.

Limelite's multimedia keys are all GTK+ “stock” labels. Stock labels are a pool of commonly used labels that GTK+ provides. It is always a good idea to use these labels when possible, as they will provide a localized string and a themeable icon in most cases. For this reason, stock labels usually are safe from an accessibility standpoint.

The one key that should concern us here is the karaoke toggle mode button. This button contains nothing but a microphone graphic. If you select it in Accerciser, you will notice there is no string representation present. A good place to double-check is in the Interface Viewer, under the Accessible section. Here, you can see there is no description for the Accessible either.

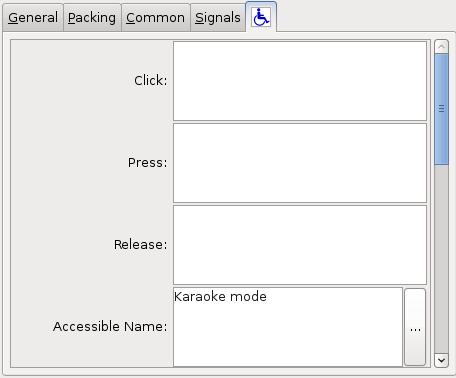

This situation easily can be ratified by directly naming the Accessible object through ATK's atk_object_set_name() function. If your UI is defined with Glade or GtkBuilder, you should be able to set the Accessible's object name in the Accessibility tab.

Figure 4. Glade-3's Accessibility Tab

Of course, the above solution will not make your interface any more clear to a user without an assistive technology. A tooltip would be a good choice in this case, both for general usability and accessibility. When a tooltip is set for a widget, GAIL automatically uses the tooltip's text as the Accessible object's description string. Assistive technologies could utilize this description string.

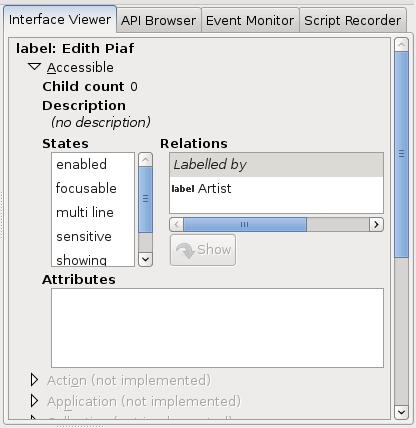

When sighted users see Limelite's UI, it is obvious to them what the relationship is between the labels. For example, it is clear that the Artist label denotes the fact that Edith Piaf is the performing artist of the current track. This is clear because of the table-like spatial layout of the labels: on the left are the field names and on the right are the field contents.

A screen reader will have trouble conveying this relationship between the two labels to blind users. AT-SPI exposes all of these labels as a flat collection, and GAIL has no way of automatically determining the labels' relationship to each other.

For this reason, such relationships need to be defined explicitly by the application author. If the application's UI was defined via Glade or GtkBuilder, we could easily declare the proper relationships in the Accessibility tab in each label's properties. If our user interface is written pragmatically, we will have to use ATK's API.

With Limelite as an example, the label containing the Artist string needs to have a “label-for” relationship with the label holding Edith Piaf, and the Edith Piaf label in turn needs to have a “labeled-by” relationship with the label holding Artist. Similar reciprocal relationships need to be defined for the Title and Album fields.

Finally, in the Accessible section in Accerciser's Interface Viewer plugin, we could verify that the defined relationships are coming down the wire and are provided to the assistive technology.

Figure 6. Relations as Seen in Accerciser

It is hard to separate usability from accessibility; more often than not, the two terms are synonymous and require your sound judgment. But, if you keep a few simple principles in mind, developing an accessible application is an easy and straightforward task. Tools such as Accerciser allow you to review your program's interface from the assistive technology side and make informed choices in interface design.