This article is an introductory piece to get you thinking about the Linux Desktop and all it can do.

So, you've been playing around with Linux for a few years now—running a file server here, a firewall there—but you're finally getting around to migrating your desktop away from Windows. After all, it's either Linux or Vista, and you don't fancy your whole system being locked down with badly implemented DRM or crippled by system requirements. Because when must a mere operating system need 15GB of hard drive space, 512 MB of RAM and a 1GHz CPU just to boot up?

Moving from Windows-land isn't merely a matter of changing the operating system. Unless you're keen on setting up CrossOver Office and moving all the compatible applications across (a problematic enterprise), you're going to have to learn a few new programs that do the same jobs on which you depend. But, before you learn those programs, you need to know what they are.

Based on a thoroughly informal and unscientific survey of those who tolerate me best, I've drawn up a list of the things most people do or need access to on their computers every day. It turns out that most people, at least in my demented little corner of the universe, still use their computers for a fairly narrow range of tasks—certainly more tasks than ten years ago, but not many more. Those tasks fall broadly into four categories: Office, Graphics, Internet and Entertainment.

Believe it or not, even though it's not how people spend most of their computer time, office software is the corner of the computer market of which people are most aware. And, why wouldn't they be? Office software is what we use to manage finances and priorities, create presentations, keep schedules and write letters, papers, diaries and books.

Of course, what you're going to need on your desktop usually is not the same as what you'd need on a work machine. Nevertheless, being a small-business owner, I tend to pick my software with an eye toward openness of data, migratability, interoperability and room for growth. In other words, I want to be able to get at my data from a number of programs, not only the one with which I created it. I want to be able to migrate painlessly to another software package should my requirements grow or change enough that I need to change my applications of choice. I want the programs I use to be able to talk to each other and to other programs out in the broader world. For example, if I write a short story and send it to a friend to proofread and mark up, I want her to be able to read what I send, and I want to be able to read her annotations in red text when she sends it back. I also want my software to be able to do more than I need right now, because if my needs grow, it's less bothersome to learn a new aspect of an existing program than to bring in a support application to supplement it or to migrate to a whole new backbone. Because I have to deal with this stuff every day, I tend to take it into account when recommending software.

So, to start off with our office software, it's best to kill four (well, three and a half) birds with one stone. Most people need to write and edit documents, track numeric data on a spreadsheet and create PowerPoint-style presentations for work, church or underground revolutionary cult meetings (you know, like Linux user groups). Sometimes, people also might want to create a database in an Access-style graphical environment to keep tabs on cult membership or lists of evangelism projects.

Evaluating office software in Linux, when coming from Windows, can be quite dizzying. With KOffice, GNOME Office, OpenOffice.org and a whole raft of word processors and spreadsheets, it's easy to become overwhelmed.

But, for my money, the OpenOffice.org suite stands head and shoulders above the rest. It reads and writes more formats better, and it's less crash-prone and more versatile than most of the alternatives (KWord from the KOffice suite being a notable exception, as it can double as a layout program in a pinch). OpenOffice.org is more resource-hungry though—its only major drawback. High-end spreadsheet users who require complicated scripted math also may want to check out Gnumeric (from GNOME Office) to supplement their office software, as its functions are more powerful.

Aside from the traditional office suite, good bookkeeping software probably is the single-most basic function people require of their computers when the computers are employed as tools. Let's face it, of all the sticking points for Windows-to-Linux migration, this ranks right up there with “my games won't run” and “I can't do without Photoshop” as one of the biggest complaints. Nobody wants to give up Quicken, and less than nobody wants to re-enter years of checkbook, credit and tax records from scratch.

Two good candidates exist in this arena—good meaning, works well, reads and writes Quicken files painlessly and doesn't require special skills to set up and administer. Of the two options, KMyMoney and GnuCash, the former is better-suited for home finances and the latter is better-suited to small business. Both are easy to use and easy to set up, although I prefer GnuCash both for its accounts payable/receivable and invoicing capabilities, and for its extensive and far-above-par documentation. It also interfaces nicely with on-line banking standards.

Although not something that generally is at the top of anyone's list, everyone needs a good PDF reader. Fortunately, not only is Adobe Acrobat Reader available for 32-bit Linux, but also two excellent PDF/PostScript viewers are available in the open-source realm with very comparable feature sets: KPDF (bundled with KDE) and Evince (bundled with GNOME). Neither rises quite to the level of Acrobat Reader—support for locked e-books is missing, for example—but both have one key edge on Adobe's current offering. Because they're open source, they are available for 64-bit systems as well as 32-bit systems, without having to mess with goofy workarounds and wrappers.

Time and communications management are the final stone in our office software rampart. Again, the Open Source world provides an embarrassment of riches: Sunbird and Thunderbird from the Mozilla Project, Kontact (which includes KMail and comes bundled with KDE), Evolution, Pine, J-Pilot—the list seems endless. It's possible to lose entire weeks evaluating the finer points of each (and each has many fine points). However, most people need a good task manager, a good calender, a good e-mail client with great spam filtering, and a way for all of them to talk to each other while being fairly worm-impervious. Of all the above, only two packages put this all together: Kontact and Evolution. Kontact is more heavily integrated in KDE, and Evolution has good integration with GNOME. But on balance, Evolution is more spry, has a better interface design and is easier for the average end user to administer without sacrificing quality and sophistication. Kontact is well on its way to this point, as is the Mozilla Sunbird/Thunderbird combination, but neither has risen to Evolution's level yet. Evolution offers a further advantage to small business users in that it interfaces with popular groupware applications such as Outlook and WebDAV. Granted, most people don't need groupware, but they do need a way to keep track of what's going on in their lives, and Evolution does the job swimmingly.

Bar none, the one thing that people do most with their computers is live on-line. Web browsing, social networking, instant messaging and e-mail are the most vital ways the postmodern Webizen stays in touch with the rest of the world. We've already touched on e-mail. The other non-browser-centric way people keep in contact is via instant messaging. There are a number of IM clients on Linux; some of them are protocol-specific (such as Amsn, which also supports audio/video conferencing for the Microsoft Messenger Network), and some of them are universal. The best of breed for the universally compatible ones is Pidgin.

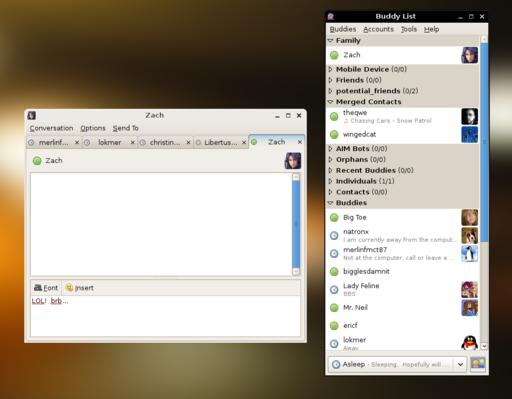

Figure 4. Pidgin sports a multiprotocol buddy list and a tabbed message interface to keep your chats well organized.

Once known as Gaim, but forced to change its name due to a trademark dispute, Pidgin is a multiprotocol instant-messenger client with tabbed message windows and an impressive array of plugins, including support for two very powerful encryption schemes to keep conversations private. The interface is simple, the program is easy to use, and it doesn't get in the way—all must-haves in an IM program. Pidgin doesn't support audio or video chat (few clients for Linux do), but all the other great peer-to-peer conference features to which users are accustomed are readily available.

Of course, when talking about Internet software, one must discuss the granddaddy of all Net software, the Web browser. Although there are a lot of viable options for simple Web browsing, if you're looking for something that will give you tabbed browsing and RSS feeds, support Flash videos and games, let you watch audio and video in embedded Flash and JVM players, and give you good, intuitive privacy management with a reasonable level of security, there is only one choice, Mozilla Firefox.

A few years back, this wouldn't have been a relevant category, but between the ubiquity of digital cameras and the glut of presentation software, everybody needs a graphics package—two of them, actually: one to organize the photos (otherwise, how are you going to find that perfect shot among the thousands you rattle off each year?) and the other to edit them.

Organizing photos is a tricky job, though it's one that people are a lot more familiar with in these days of Flickr than they were ten years ago, when the shoebox at the back of the closet overflowed with pictures to sort and put in albums...someday. In the Mac world, everyone uses iPhoto. It's ubiquitous, it makes slideshows, and it does rudimentary adjustments in the program. On Windows, there's Picasa, which is focused more on printing than indexing. On Linux, there's F-Spot and digiKam. F-Spot is a rudimentary, but user-friendly, indexing system. digiKam, on the other hand, is far more sophisticated, with integrated color management, gallery creation, iPod interface, slideshow and calendar creation, and RAW format handling, all underneath a well-laid-out interface. In this game, it's the clear winner.

For graphics editing, there isn't such a clear winner. The field is dominated by two very robust contenders: Krita and The GIMP. I published an in-depth article in the July 2007 issue of LJ reviewing Krita and its advantages over The GIMP. The philosophies of the two programs are very different, as are the interfaces. The GIMP has a broader user base at the moment and more available plugins, and Krita offers more professional color management and a broader array of basic editing tools. Currently, they're very different programs, and from the point of view of the lay user, a lot is going to boil down to personal taste in interface. Either will serve very well.

Between Google video, podcasting, video podcasting, integrated DVD players and USB-powered...well, let's call them “personal exhilaration devices”, the computer now is an entertainment center. Projects like MythTV let you literally build an entertainment appliance out of your PC, but even your desktop has to have a good multimedia backbone in it, or you might get frustrated and bored. We can't have that, now, can we?

So, let's start with home videos. You shoot them, and then what? Are you really going to spend months of your twilight years rewatching ancient DV tapes in real time? Of course not. But, you can edit them and export them to DVD or YouTube to share with your family if you install Kino on your system. Small, fast, feature-loaded and stable, it's the Linux answer to Windows Movie Maker and iMovie.

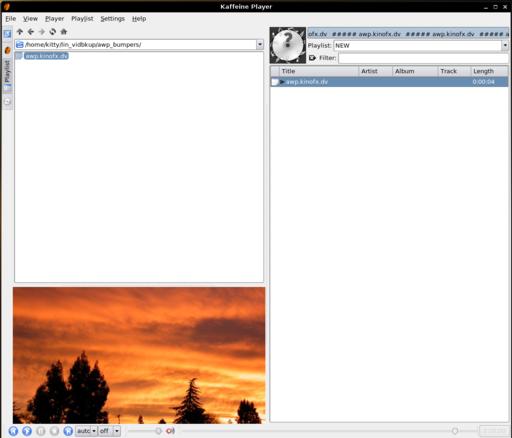

Of course, playing those movies you make and the DVDs already on your shelf, is another matter. You need a good, all-purpose media player. In Windows-land, you need QuickTime, RealPlayer, Windows Media Player, Flash Player and WinDVD to cover everything. In Linux, you need only one program, though you have a choice of three that are quite excellent: MPlayer, Xine and VLC. They all use FFmpeg as a back end, which is both highly robust and versatile. All three also can call upon Windows-native codecs to decode proprietary file formats. The choice between them primarily is one of taste. MPlayer can be run from the command line as well as with a GUI, it has a very stable Firefox plugin, and it contains an excellent set of command-line encoding and stream-ripping tools. Xine (and its front ends, like Kaffeine) tends to have the friendliest interface. VLC is equipped to broadcast Net streams as well as rip them and transcode them natively in the GUI. I personally keep all three around, but any one of them will do you well, depending on what you're looking for. In practice, you'll wind up using one for your viewing pleasure.

Figure 10. Kaffeine's playlist building interface, with a file browser on the left, a preview window under it, and the playlist on the right. Kaffeine is a Xine front-end.

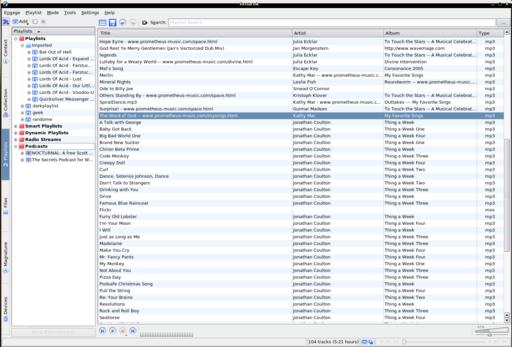

You'll also need a podcatcher and media library organizer and player similar to iTunes. In this field, Amarok stands alone. It also allows you to select the back-end engine you prefer (GStreamer, Xine and so on) and will play pretty much any audio format under the sun. It includes integrated id3 tag editing, a very intuitive database index, a MusicBrains store interface and lots of fun little extras for dealing with iPods and other portable media devices.

Figure 11. Amarok is the ultimate podcatcher/portable media player/sync manager/music library manager/player.

Finally, you're going to need something to burn all the CD compilations, DVDs from videos you've edited, and backups of your data. The best and most fully featured solution you can get for this is K3b. It supports data CDs and DVDs to a variety of formats and standards, rewritable media, video CDs and DVDs, burning from a variety of ISO types, and even self-booting media CDs and DVDs with micro-operating systems (eMovix discs).

The good news about Desktop Linux isn't merely limited to the fact that you can do everything—or nearly everything—on Linux that you need to do on a desktop system. The really good news is that most of these programs—Pidgin, OpenOffice.org, Evolution, MPlayer, THE GIMP, Firefox, GnuCash and VLC—work on Windows, so you can ease yourself into the Linux/Open Source world in stages.

Is this the Year of the Desktop for Linux? That's something history will decide, if it even cares. But, one thing is without doubt: Desktop Linux has arrived.