Trolltech's Qtopia SXE takes a stab at making open-source phones more secure.

No one wants an insecure system, especially on a mobile or VoIP phone. Both users and operators want to feel confident that their phones won't be used secretly to send thousands of spam messages or viruses or to transfer huge files. Linux in the mobile space opens doors to everyone—including developers of malicious code. A locked-down and secure system does not necessarily mean the source code is closed.

Figure 1. Qtopia's Home Screen

The last thing people want on their phones is a malware application that secretly sends their details somewhere or launches a DOS attack using their costly GPRS account. Together with the Linux Intrusion Detection System (LIDS), Trolltech's Safe Execution Environment (SXE) delivers a safe environment in which to allow untrusted applications to be executed. Without SXE and LIDS, an unsuspecting user could install an unknown package. This could launch Qtopia's QCop, which handles Qtopia's interprocess communication (IPC) with LD_PRELOAD set to its own libc library. This means that its own code is loaded instead of the known libc in the system, which could have disastrous results on the user's data, or worse, disrupt emergency communications.

Trolltech has an answer.

Trolltech recently announced the GPL version of Qtopia that includes SXE, as well as telephony libraries needed for GSM and VoIP-enabled phones. Trolltech has spent many person-hours developing SXE to help ensure that both operators and users are confident about installing native compiled applications. I say person-hours here because the lead developer for much of SXE's life was Sarah Smith—Trolltech's first female developer.

SXE is a little like a firewall. It prevents applications from accessing unauthorized services and hardware through domain controls. It goes beyond just plain sandboxing applications, which can blindly deny programs access to system resources. It applies policy rules for each program component and IPC. Qtopia applications send an IPC or QCop message when they want to open a window or send an SMS.

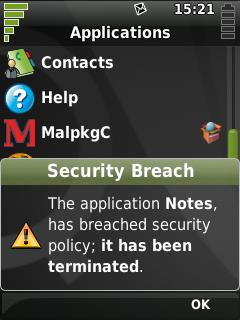

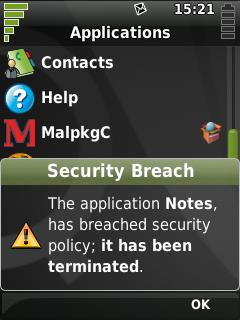

Upon installation, an application specifies what security domains are needed to function and is sandboxed by Qtopia. If the program is executed and then tries to access services beyond what it has been awarded, a security breach is logged, and the application is terminated and disabled. A dialog and SMS message are issued to the user regarding the breach. LIDS can complete the safe environment by controlling access to hardware, system-level services, programs and files.

The Qtopia Greenphone is an example of a working SXE and LIDS implementation, and this article discusses Qtopia version 4.3.0. The Qtopia open-source version, announced recently for the FIC's open-source Neo phone, also would benefit from SXE and a LIDS-enabled kernel.

An SXE application starts with a developer creating a Qtopia application and packaging it in a Qpkg, which is based on the Itsy Package, but has a few security issues resolved. Namely, Qtopia does not allow an application install to run arbitrary scripts, but also, the package must specify which domains it needs access to in order to run. Qtopia then allows (or denies) that package only those domains that it requests.

An SXE domain is simply a name for an allowed access rights policy. Some of the default domains and their access rights in Qtopia are:

docapi: user documents.

pim: Personal Information Management data.

window: graphic display.

graphics: full-screen graphics display.

net: access to WAP, GSM and GPRS.

Qtopia uses many more domains, and some of them, such as the base domain, should never be allowed access by any untrusted application. Operators or integrators can use the default Qtopia domains or create their own.

The third-party developer then specifies, in the package control file, in which domains the application needs to function. Much like a legacy ipkg, a qpk is simply a gzipped tarball of the file structure where the application lives, a desktop file much like those used in KDE and GNOME, plus a control file that specifies parameters, such as the application's name, maintainer, domain, file size and so forth.

The Greenphone SDK makes this easy with the use of the gph script, which can configure, compile, build the package and install or run it on the Greenphone. The developer needs to know only which domains the application is going to use. Starting a debug build of Qtopia in SXE_DISCOVERY_MODE, with SXE logging turned on, can help log these domain requests and subsequent denials. There is a significant performance decrease while running in discovery mode. It is only for the debugging process and not a final release. The developer then can add the appropriate domains to the application's .pro file.

After configuring the Package Manager to see the feed server, Qtopia reads a plain-text file named packages.list on the server. This file contains a list of all the packages available on the server, the domains the package is requesting, as well as the description, name, maintainer, size, license and md5sum of every package.

When users want to install a new package, they select it from a list. Users then are prompted with a dialog containing the specific domains that the application is asking to access (Figure 2). Users have a choice whether or not to install. The package then is downloaded to temporary storage, installed and sandboxed. By default, the untrusted packages live in /home/Packages, with the md5sum used as a directory name—for example, home/Packages/1e67fa93917fedb17f575fe0f2ee2cd8/bin/screenshot.

Figure 2. Package Installation

The Packages directory has a file structure, such as bin/lib/pics/, that symlinks to where the real binaries live. These symlinks use the md5sum in the name, such as 1e67fa93917fedb17f575fe0f2ee2cd8_screenshot → ../1e67fa93917fedb17f575fe0f2ee2cd8/bin/screenshot.

This file path is known to Qtopia, so it can find your shiny new application, and then adds it to the main applications list. This information now lives in the Qtopia content database. In previous versions of Qtopia, all this data simply lived in the filesystem, and Qtopia scanned to find the applications. The Package Manager then runs the sxe_sandbox script to create the LIDS rules for this application.

Users start an untrusted application by clicking on its icon from the main menu. In Qtopia versions previous to 4.3.0, the untrusted and installed applications were accessible from the Installed Packages application. To make sure an application tries to access only the domains it was granted, Qtopia monitors service access requests with SXEMonitor. If the application tries to access something it did not initially request, such as the phonecomm domain, a breach is registered (Figure 3). The application is terminated, and Qtopia alerts the user with a dialog. It also, however, sends the user an SMS message directly to the Messages inbox. If this application continues to create breaches, Qtopia disables the program completely.

Figure 3. Security Breach Alert

Figure 4. Installed Package in Main Menu

LIDS plays an integral part in all this. SXE works together with LIDS policies to make sure files that should not be accessible are not accessed. You must have LIDS enabled in the kernel to take advantage of SXE. The Mandatory Access Control (MAC) system in LIDS controls lower-level filesystem access. Without it, Qtopia can deny applications access to Qtopia services and tasks in the domain policies, but there would be nothing stopping an application from changing those access rights to something more advantageous for a malicious application.

Figure 5. Security Info Showing SXE and LIDS Status

A number of script templates ship with Qtopia, which live in etc/sxe_qtopia, that help with the creation of LIDS rules during both the root filesystem creation and package installation. The LIDS-enabled Greenphone writes these policy rules during the first boot after a flash of a system update. An operator can, of course, do this to the filesystem before deployment.

When integrators create a new application or service, they need to add them to Qtopia's etc/sxe.profiles file. This file contains a list of domains and the services and QCop messages associated with them. It is processed by Qtopia at install time to create SXE policies. Integrators also might need to add it to the Package Manager's source code, so it can display the domain's verbose characteristics to the user. This helps users make at least a knowledgeable choice as to whether to install the package.

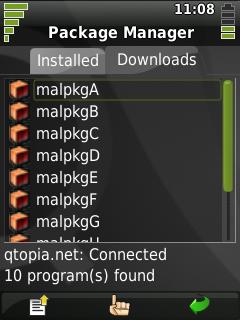

Qtopia.net has two feeds set up with simulated malware packages to test, for both the 4.3.0 Greenphone (qtopia.net/packages/feed/4.3/greenphone) and its SDK (qtopia.net/packages/feed/4.3/sdk). There, you can get the latest Greenphone SDK to try out yourself (Figure 6).

Figure 6. List of Fake Malware Packages on Qtopia.net Feed

To enable a LIDS kernel, download the LIDS patches from the LIDS Web site, build the patched kernel, build the LIDS filesystem and configure the policy scripts. Qtopia comes with scripts to help define LIDS policies based on domains. For example, the script etc/sxe_domains/sxe_qtopia_bluetooth creates a LIDS rule like this:

lidsconf -A POSTBOOT -s ${BIN} -o LIDS_SOCKET_CREATE -j ENABLE

for applications that are granted access to the Bluetooth domain.

I won't go into the gory details of creating LIDS policies, but more information can be found at the LIDS Web site (lids.org) and in the Trolltech documentation (doc.trolltech.com/qtopia4.3/sxe.html).

SXE and LIDS can make your Linux phone more enjoyable and worry-free by giving you the confidence that untrusted applications you download will do only the things they are allowed to do.