There is history here. We first covered Jabber in the September 2000 issue of Linux Journal, more than seven years ago. At the time, Jeremie Miller, who invented Jabber, told me at least five years would pass before Jabber's protocol—later dubbed XMPP and approved by the IETF in 2003—would establish itself as a de facto standard. He was right.

We've stayed in touch over the years, as Jeremie's interests have spread outward from messaging and presence to other subjects—especially search. I guess it was about two years ago that he began to question whether search needed to be a single-source thing (for example, Google or Yahoo). That was when he also started talking about his new search project, called Atlas. Whenever I'd ask him what he was working on, he'd reply, “Atlas”.

I was all for it, because I've felt from the start that search engines are essentially kluges meant to overcome a directory deficiency in the Web itself. I've also thought that, although there was good to be found in the chaotic nature of everything to the right of the first single slash in every URL on the Web, there was something inherently wrong about relying on massive commercial advertising-powered search engines—with their bots and crawlers and proprietary weighting algorithms chugging through constantly updated indexes stored in hundreds of thousands of servers—just to find stuff. And, although I agree with David Weinberger that Everything Is Miscellaneous (the title of his excellent new book), I don't like relying on Google, Yahoo or MSN alone (usually just Google) to tell me what I mean when I search for something. Nothing matters more than meaning, and I don't like seeing it supplied by what Jeremie calls a “text box dictatorship”. In a May 28, 2007 blog post, he asks:

Why in such an advanced civilization have we become Knowledge Peasants who are so easily placated by the black magic of our Goovernor? Am I the only one wondering why these commercial boxes own such an important social function: what everything means?

The answer, he says, is:

Open open open! Open source, open distributed grids, open algorithms, open rankings, open networks of people cooperating to provide resources. The future of search is in open cooperation (and competition) based on a Meaning Economy—create meaning, exchange meaning, serve meaning.

My vision begins with an open protocol, allowing independent networks of search functions (crawling, indexing, ranking, serving, etc.) to peer and interop. All relationships between these networks are always fully transparent and openly published. Networks exchange knowledge between them, each adding new meaning to the information, each of them responsible for the reputations of their participants and peers. This is the very foundation of a Meaning Economy.

Tomorrow now has a meaning that we can all help build.

Jeremie hasn't been the only one on the open search case. Jimmy Wales, prime mover behind Wikipedia, attracted attention in December of last year when he said, “I want to create a completely transparent, open-source, freely licensed search engine”—as part of Wikia.org, a community development companion to Wikipedia. In a December 29, 2006 interview (www.wired.com/techbiz/it/news/2006/12/72376?currentPage=2), Wired asked him for specifics about that. Jimmy's reply was, “We don't know. That's something that's really very open-ended at this moment. It's really up to the community, and I suspect that there won't be a one-size-fits-all answer. It will depend on the topic and the type of search being conducted.” Subsequent interviews were similarly speculative and open-ended.

Then, on May 1, 2007, came news that Jeremie was joining the Wikia Project. In a prepared statement (news.com.com/2100-1032_3-6180379.html), Jimmy Wales said, “Jeremie is a brilliant thinker and a natural fit to help revolutionize the world of search....I believe Internet search is currently broken, and the way to fix it is to build a community whose mission is to develop a search platform that is open and totally transparent.”

Atlas was unveiled in a post to a list on July 5, 2007 (lists.wikia.com/pipermail/atlas-l/2007-July/000000.html). In that post, Jeremie said his “large vision” is “enabling search to become a part of the Internet's infrastructure. Building on Atlas as an open protocol, search can become a fully distributed and interoperable world-wide community. All of the participants can interact openly and in any role where they believe they can add value to the network.”

As for architecture, he offered this:

There are three primary roles within Atlas:

Factory—responsible to the content.

Collector—responsible to the keyword.

Broker—responsible to the Searcher.

Each of these actors must interact with the others to complete any search request. Any two roles could be performed by a single entity (whereas if all three are performed by one entity, the result would be a traditional, monolithic search engine).

A Factory is akin to a crawler in today's search engines. An Atlas Factory must fetch and process the content as intelligently as possible, performing analysis (such as Natural Language Processing) and normalizing it into distinct units. A Factory shares its highly refined and processed output with one or more Collectors based on who they believe is best utilizing it.

A Collector absorbs and indexes output from one or more Factories, with one primary goal: ranking. An Atlas Collector must provide the most intelligent ranking and relationship analysis possible. A Collector has to compete for the output of a Factory, as well as compete to provide the best ranking quality for Brokers.

A Broker must provide a Searcher with the best possible results. It does so by combining diverse ranking results from Collectors and also by retrieving content from the original Factories. This last step, a Broker interacting with a Factory, is critical to maintaining a balanced ecosystem. All Factories must be aware of and approve how their results are being used and by whom.

Reputation and reward is bi-directional between all parties (Factory-Collector, Collector-Broker and Broker-Factory). Each entity may choose to interact on principle (free, Commons), attribution (results provided by), or commercially (as a paid service). The Atlas protocol is purely a facilitator and does not restrict how the relationships between any entities are formed. In considering these motives for the various entities, it's likely that the free-based networks will tend to become more specialized, commercial ones will compete on quality, and attribution-based networks will mature in both directions.

This simple yet powerful division of roles, responsibilities and relationships will result in a distributed economic foundation for an Internet Search Infrastructure. The wire protocol and further definition of the interactions between these entities is openly evolving; anyone interested is welcomed to join the discussions and see the initial proposals at lists.wikia.com/mailman/listinfo/atlas-l over the coming weeks.

As a kind of gauntlet, Jeremie threw down a summary challenge, “Nobody will beat Google, but EVERYBODY will.”

Vigorous discussion ensued, as a rapidly growing community of developers began getting into what Jeremie calls “the dirty work of building it openly now”. As that work began, I asked him if it would be cool to flow some of our conversation over here to Linux Journal. He said sure, so here it is.

DS: There is always this tug between monolith and polylith. The irony of the Net as a Giant Zero (world of ends) is that it is entirely polylithic—or wants to be. Centralizing a future polylithic protocol into a monolithic service is one way it starts. But the end state is polylithic.

JM: I agree, it's inevitable. It's the being of the Net itself that ultimately demands it, but Google is fighting to be a monolith for as long as possible...and that's fine, they'll embrace Atlas when they see it providing value.

DS: In your announcement [above] I see the seeds of a credit-where-due-based economic system—one in which we might obtain finders fees, or something like that, as value is given for service performed.

JM: The attribution-based model, yes. Absolutely the middle man needs to be involved in the transaction. Atlas doesn't flow the money, but it does flow the information and provide a framework. The same with advertising. Really, contextual ads are very helpful. I rely on them as a tool when using Google search. And in fact, that model is the best form of fighting Web spam.

How the system works, and who is involved in the flow of information, is completely transparent, so the three actors—a Factory, a Collector and a Broker—are all involved in providing a search result. A Broker works on behalf of the Searcher. They have relationships with the appropriate Collectors, plural, and perform the queries—assembling all the relevant “Knuggets” they get back from the Collectors, valuing them based on whatever metrics they want, including talking to a “sponsored” Collector who serves only commercial results, any “local” Collectors for regional areas, and so on.

Competition is fierce when anyone can be a Broker for almost no cost other than relationships. So, a Collector has one job, provides relevant results, and has to compete with anyone else to do so. And, it can judge the relevancy via any algorithmic, human-reputation-based, or combination.

DS: Open source at the production end has always been a meritocracy. Seems to me the equivalent with Atlas to “show me the code” is “show me the results”. Or at least, “show me the relevancy”. No?

JM: The Factory is managing commodity access to the refined content, doing all the work of normalizing the Web. Search results are just merit: who has the best. And a Broker going to many sources, many Collectors (there can be lots of them) gains lots of merits in different forms. So foxmarks has a great database of deep links that are very important to people. That way Mitch can serve high-quality results but only for certain categories of queries. And Wikipedia can serve another category of queries with high relevancy—as can local yellow-page-style systems, as can social networks for people queries.

DS: I see implicit in this a respect for the snowballing nature of knowledge, both for individuals and for groups. To be human is to grow what one knows. Authority is the right we grant certain others to contribute to what we know—and to change us in the process. Knowing more makes me different. As has been said elsewhere, “we are all authors of each other”.

JM: Yes, the fundamental unit of Atlas is a “Knugget”, a Knowledge Nugget essentially, a search result. A Factory adds value based on what it knows about the content; a Collector adds value based on what it knows about keywords and ranking Knuggets; and a Broker adds value based on what Collectors it knows and what value they provide in aggregate.

DS: Wikipedia, in growing its own relevance, is an interesting example. I've been looking at radio stations and Webcasters. Wikipedia on the whole is a great source of info, but it's far from complete. And, it needs a better way to stay complete than just relying on narrow subject obsessives to stay on top of the current narrative. Search results that feed into better Knuggets that turn into better Wikipedia entries should be a Good Thing, no?

JM: Yes.

DS: Is a Knugget “something somebody wants to know”? I like the word. How about if it's a combination of keywords that may change over time?

JM: A Knugget is one unit of context, as I define it. It may be a title and a link; it may be a sentence saying something about a noun; it might be a row from a table of things. It's human-defined and, therefore, very fuzzy by its very nature. It's “What would a human recognize and make some sense of, out of context of anything other than what's contained inside of it?” The Web is human, not machine, and Atlas reflects that.

DS: I like contextuality. The summit of Mt. Everest can be an elevation, a sum of climbers, a single fact (such as, it is marine limestone).

JM: Yes. The very nature of Atlas is to demand that a Factory produces the best Knuggets, that a Factory “understands” the content as best as it can. It is a model that rewards human understanding and value first. All derivative knowledge is built atop that foundation, and we can reduce all of these inflated DB/schema disasters, which all serve the machine first. Atlas works in the same way that the Internet served people first, and servers/data centers second—and the Web content serves people first and software second. Search-as-Internet-infrastructure must serve people first.

DS: Yes. I think there is a Static (traditional Google) vs. Live (human, now, evolving) distinction here. Allow me to quote myself at a bit of length: “And as for live feeds of Knuggets as they are produced, any content provider can get the most value by generating these feeds of Knuggets into Collectors they trust, search results can be instantly rewarded, a Searcher can find that breaking-news article immediately.”

One becomes an Atlas Broker just by being involved, I would gather.

JM: Just by searching, and knowing whom to ask for results.

DS: How do you want to seed this thing? Where does actual use start first?

JM: An Atlas Broker should be living here in my IM client, using all this great context, LOCALLY, to search my IM history as well as provide the best relevant search results from any content store I want it to.

DS: Who is the Broker?

JM: The Broker is a human. The Broker is just a service that uses as much context as you, the Searcher, wants to give it, and it talks to many Collectors to merge/provide the best results.

DS: So, how are you seeding this thing?

JM: I'm already starting to set up Atlas Factories. We may announce a contest to build open-source Collectors that can do different/cool things with, say, the Internet Archive. Once Atlas starts to breathe on its own, and can publish that archive either openly or gated (attribution-based or paid), or if it can rank Web results better for a certain class of queries, it can use that data as a Collector and offer that again, openly or gated. But that's speculative and premature. It's all wide open at this stage.

DS: Outstanding. I know some investors have leaned on Technorati to blow away the archives because that's not what they search. Yet.

I guess I need to get a sense of what a search might look like, and how it would come up with stuff that's different from Google's static search and Technorati's live (chrono) search. Would I go to atlas.wikia.org to search? Or to...where? Or is that question too static or site-based?

JM: I don't have a “static” presence for Atlas yet. Kind of refusing even to do that for whatever reasons. Just a link to the mailing list for now is all there is. Someday there will be a presence, but the discussion is more important right now. I like it that all people can do at the moment is discuss.

DS: I'm just looking at how to help people conceive What It Is. Is it a site? A service that other sites, or even IM systems, or cell-phone apps, can use?

JM: Atlas is an idea, a model and, ultimately, a communication system between two people: the one that wants to learn and the one that wants to teach/share. It's just another communication platform, but the people talking don't know each other yet. Like all good Internet systems, it will live under the hood, behind text input boxes everywhere.

DS: In that respect, it's more like the Jabber “platform” than the AIM or Skype “platforms”.

JM: Yep, in that Google, Yahoo and Ask are the IM silos, and Atlas is the distributed/open Jabber model.

DS: Good. I get that. Is Atlas code that sits somewhere and is given a bunch of stuff to look at? If so, where does it live? Is there a drawing we can use? Some kind of simple whiteboarding?

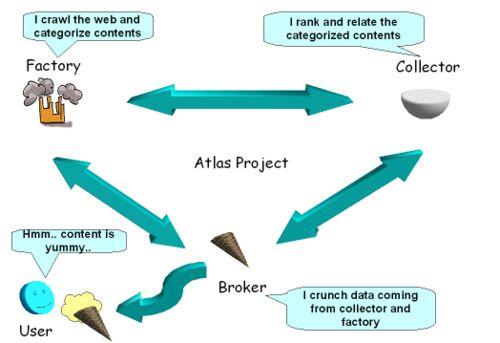

JM: Where stuff is almost doesn't matter. As far as visualizations go, the “logical” one is really Factory→Collector→Broker, but the technical one is more of a triangle, as the Broker talks to the Factory in the end to get the Knuggets...but basically no, there's nothing visual yet. A Factory is going to “look” like a pile of search results ordered based on the content source alone. A Collector will aggregate/order them. And a Broker will aggregate from lots of Collectors the ordered results, merging them, getting the snippets from the Factories they came from, and presenting them. By the way, someone made the first visualization of the model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Visualization of the Atlas Model (from search.wikia.com/wiki/Atlas)

DS: Where would they live? The actors...Factory, Collector, Broker...or the code for it all?

JM: Oh, anyone can run any of them. There will be open-source projects to provide each of them. But, there should be thousands of each, running everywhere around the world. Just like Jabber, e-mail and Web servers. They just talk to each other with a protocol. There can be locale-based specific instances, ones for different languages, ones for types of content (images, videos), ones for topics (gaming, finance)—whatever people want to do/specialize in. People can run them for whatever reasons they want. A Broker is really the endpoint, so the nature of the search has the Broker engaging the relevant Collectors. A Broker is doing what the word really means, brokering your search to lots of sources for the best results. A Broker is what would likely be built in to your browser or whatever is driving an input box anywhere.

DS: I like the way it maps to the real world.

JM: It doesn't force an operational model, and it just goes with whatever motives people have to run it. The good part is that it will work only if people find it valuable enough to run it; those are the best kinds of systems. So is all of this clear as mud?

DS: Good mud!

JM: Thanks.

For more, look up Jeremie and Atlas on Google.

Until you can do the reverse.