The time has come to consider moving that expensive, high-maintenance Windows system to a sleeker, more robust Linux system. The gap analyses have been done, the meetings held, the presentations complete, and now it's go time. Although installing and configuring a Linux server back end can be challenging, we all know that users aren't going to care about that. What they want is uninterrupted functionality so they can continue doing their jobs. Although migrating users from applications such as Microsoft Office to OpenOffice.org is generally an intuitive task, the 800-pound gorilla that's keeping you up at night is e-mail and groupware. How are you going to provide and manage Microsoft Outlook-like functionality to the masses? In a word, Citadel.

One of the understated wonders of the Free and Open Source Software world is the Citadel Groupware Server (www.citadel.org). Controlled by a single developer, Citadel started life in 1987 as a UNIX version of the already-existing Citadel-CP/M application. Almost 20 years later, the modern-day Citadel boasts all of the functionality of a mature groupware server. One of the miracles that Citadel can perform is providing all of the most-used functionality of Microsoft Exchange with little fuss and and even less cost.

Many modern organizations are coming to the realization that their IT budget is largely controlled by Microsoft's licensing fees and hardware requirements. Although organizations can prepare for some of these costs, many are looking at Vista with trepidation. Although the hardware requirements for Vista aren't obscenely over the top, many organizations still will need to upgrade their hardware in order to run it. And, sooner or later, run it they will. The hardware upgrade cycle is a never-ending source of pain for some organizations, because not only do servers and server software need to be upgraded on a somewhat regular basis, but untold numbers of workstations also need attention.

Depending on the size of your organization, your Microsoft Exchange server might be the most robust server in the closet, and finding a suitable replacement for Exchange is quite often a show-stopper. Citadel is a groupware solution that allows organizations not only to avoid upgrading software, but it also runs on a significantly lower-powered machine, thus breaking the hardware upgrade cycle for years to come.

It's always good practice to install and test everything on a test server before moving it into a production environment. Swapping out your mail server is certainly no different, and you should keep your Citadel testing as far away from your production system as possible. Obtaining and configuring Citadel is several orders of magnitude easier with an Internet-connected server, however, because you can avail yourself of the Easy Installation process.

As of this writing, the most current version of Citadel is 6.84. I highly recommend a trip by the Citadel site in order to obtain the most current version of the server and the most current version of the installation instructions. Our testing environment consisted of Debian Sarge with a 2.6 kernel running in VMware Player 1.0.2. For no particular reason, we selected the Web server installation option, but virtually any installation category should work, as Citadel installs everything it needs. In the past, we have installed and run Citadel on a Debian Sarge server proper, and in both cases the installation was flawless.

I cover the Easy Installation method here not only because it's easy, but it's also fairly undemanding on resources and therefore quite likely that anyone can make use of it. Just about the only requirement for the Easy Installation method is a working—and preferably fast—Internet connection.

The Easy Installation method requires the toolchain, or build environment, to be present on the target platform. In addition, curl (or wget) is required. If you'd like to support SSL connections to the server, you also need libssl-dev. On a Debian system, use the following command to install or verify your build environment:

apt-get install build-essential curl libssl-dev

Before installing, it is worth noting that Citadel is designed as a black box system running on your server. Part of that black box means that Citadel authenticates logins against its own user database and not against your system user database (typically /etc/passwd). If you'd like Citadel to authenticate against your system user database, you must export the IS_AUTOLOGIN variable to the environment prior to running the Citadel install, like so:

export IS_AUTOLOGIN=yes

Now that the environment is set, it's time to kick off the Easy Install with the command:

curl http://easyinstall.citadel.org/install | sh

or, if you'd prefer to use wget:

wget -q -O - http://easyinstall.citadel.org/install | sh

Citadel downloads, unpacks and starts the installation process. You need to pay attention to the installation process, as Citadel asks all the right questions, but you won't need any of your arcane configuration logs to answer them.

Citadel is humble, and although it brings a lot of power to the party, it doesn't assume that you want any of it. Citadel will ask if you want to use its built-in POP, SMTP or IMAP servers or leave any of your own up and running.

Further, there is a Web interface, called WebCit, which users can make use of to get all of their e-mail, calendar and contact information when on the road or otherwise away from their local e-mail and Personal Information Manager client. If you elect to install WebCit, Citadel won't assume that you want it running on port 80. It therefore is possible to run WebCit on a nonstandard port and leave any existing Web sites you have on port 80 undisturbed.

For the curious, Citadel is installed to /usr/local/citadel, and WebCit, if chosen for installation, is installed in /usr/local/webcit. Supporting libraries can be found in /usr/local/ctdlsupport.

Uninstalling a Citadel instance installed via the Easy Install method is easy:

Delete the three directories mentioned above (/usr/local/webcit, usr/local/citadel and /usr/local/ctdlsupport).

Remove the Citadel and WebCit entries from the inittab file (typically /etc/inittab).

Type the command init q to restart init.

Gone.

We used the WebCit Web interface to configure and use our Citadel server, but underneath the nice GUI beats the heart of a text-mode BBS. Virtually all of the configuration and much of the daily use of the Citadel system can be used via the text mode Citadel client ála the BBS scene of days gone by. Sadly, that method of communication is largely lost to most modern-day users, so we focus only on WebCit to get the job done.

Having said that, we still need to log in to our Linux server for other reasons, so we have to change the way that Citadel logs. By default, Citadel logs to the console, and that needs to be redirected somewhere else in order to get any work done. There are a variety of different ways to do this, but since Linux provides a configurable syslog dæmon, it seems logical to edit the /etc/syslog.conf file (on Debian) and point the local4 facility to a log file or somewhere else out of the way.

The first person to log in to the new Citadel Web interface becomes the administrator-level user. To create the administrator account, point your Web browser to the host and port where you told WebCit to listen during the installation, enter a user name and password, and press the New User button (Figure 1). You'll know you've become the administrator if you see the Administration button on the bottom left of the menu when you're logged in (Figure 2).

To enter the site-wide configuration, click the Administration button, and you'll be brought into a well-organized and complete settings menu. Main categories are along the top of the page, and clicking each one brings up the settings for that particular area. As mentioned, Citadel is also a text-mode BBS underneath the WebCit interface, and some of the configuration options make that quite obvious.

Although a good study of all of the configuration items is outside the scope of this article, the most important settings are under the Network and Directory (if you're using LDAP). Under the Network tab, you can enable and disable services and modify the ports on which they run. Under the Directory tab, you can specify your LDAP settings. If you're not using LDAP, you probably can leave both of these screens alone, because the Network defaults either are quite reasonable or will reflect your installation choices (Figure 3).

You may want to take a quick trip to the Access tab and make sure it reflects how you would like new users to sign up. Likely, for a corporate server, administrators will create all of the accounts and user-driven account creation can be shut off.

Sometime before letting users at the WebCit interface, you'll likely want to customize the site a bit. As you navigate through the default WebCit installation, you may notice default text banners on the site that contain the path to their locations. A good example of this is the “Welcome to My System” banner on the main WebCit log in page (Figure 1). A variety of text files exist in /usr/local/citadel/messages that can be tailored to your needs.

First things first, and before you point your mail records to your new Citadel server, you have to tell it what domains to accept e-mail for. I much prefer Citadel's way of handling this as opposed to mucking about in configuration files. To specify the domains for which you're interested in handling e-mail, click on the Advanced menu option, and then the Domain names and Internet e-mail configuration link.

In the resulting page, enter the first domain for which you want to accept mail in the Local host aliases field. Click the Add button, and continue entering more domains as your situation requires (Figure 4).

The Local host aliases field is the only setting that absolutely has to be filled out, but you may want to integrate some more-advanced functionality within this screen as well. You can specify the domains to map to the Global Address List (GAL), indicate smart host addresses if your server isn't sending mail directly or point to a SpamAssassin or real-time blackhole list (RBL) host to scrub incoming mail before it's delivered.

That's it. You now can send and receive e-mail out of your Citadel installation.

There's no technical reason why a local client has to be set up at all. WebCit exposes all of the most-used groupware functionality via a Web interface, and users can begin using that immediately to organize their lives. However, local clients do bring some power to the table, and many users won't be satisfied with a Web interface. Therefore, onward we go.

Depending on the needs of your users, a variety of Linux clients can replace Microsoft Outlook. After many setups, we've found that KDE's Kontact is the easiest personal information manager to back onto a Citadel server, so that's what we use here.

Kontact is the KDE Project's all-in-one personal information manager. In a sense, Kontact simply provides a unified interface to access KMail, KOrganizer, KAddressbook and some notes and news components.

Setting up KMail is a rather intuitive process. If you've ever set up a mail client before, you'll be able to set up KMail without issue. As long as you've set up at least one of your Citadel server's IMAP or POP servers, you can set up KMail to use either. Simply plunk in the URL or IP of your Citadel server, your account credentials and be done with it (Figure 5).

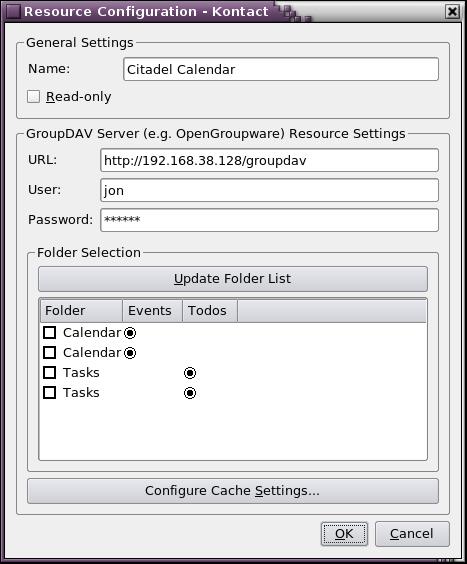

Setting up the calendaring functionality of Kontact is a little more indepth. We've found that the GroupDAV protocol is the easiest and most powerful to set up, so that's what we do here.

One of the few things you need to know is how to construct your GroupDAV URL. Quite simply, your GroupDAV URL is the URL to your Citadel server (including the nonstandard HTTP port if you've told Citadel to listen on a port other than 80) with /groupdav appended to it. In my case, my GroupDAV URL is http://192.168.38.128/groupdav.

To enable KCalendar's groupware functionality, click on the Calendar icon in the left-side pane. At the bottom of the middle pane is a section labeled Calendar. Right-click anywhere in that pane, and select Add. In the resulting window, select the GroupDAV Server option. If you don't see the GroupDAV Server option, it's likely you don't have the kdepim-kresources package installed. Install it, restart Kontact, and you should be good to go.

The Resource Configuration window opens. Enter a name that means something to you in the Name field and your special GroupDAV URL into the URL field. Your user and password credentials are the same ones that you set up when you logged in to Citadel the first time. Click the Update Folder List button, and the bottom Folder Selection pane should populate with Calendar and Tasks radio buttons (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Set up KOrganizer (Kontact) calendar for Citadel.

It seems that clicking the check boxes beside the Calendar and Tasks items would enable those items, but the system is a little buggy. In many cases, two instances of Calendar and Tasks show up, as shown in Figure 6. Further, to enable a Calendar or Tasks item, the only way that seems to work is to right-click each item and select Enable from the context menu.

Once you've enabled the Calendar, you can enter items either within Kontact or within WebCit, and the items synchronize as mail is checked or other server contact occurs (Figure 7).

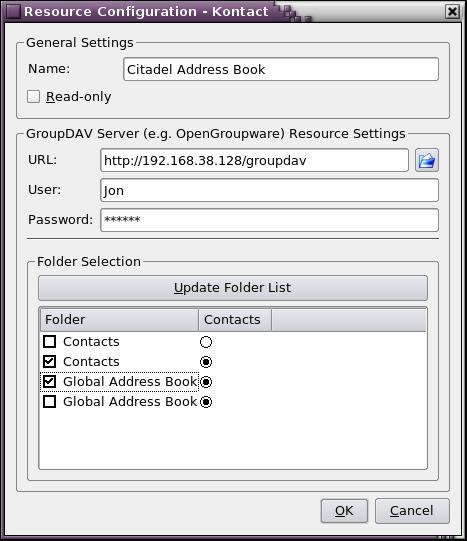

Setting up Kontact's Contacts (say that five times fast) is much the same as setting up KCalendar. Click the Contacts icon in the left-side pane. At the bottom of the middle column is a pane labeled Address Books. The right-click trick doesn't work here, so click the Add button instead. Select the same GroupDAV Server option, and fill in all the same data that you filled in for the KCalendar setup. Click the Refresh Folder List button, use the right-click-to-enable trick, and you're off to the races (Figure 8).

Figure 8. GroupDAV Settings in Kontact

As with KCalendar, once you've set up your GroupDAV connector, you can now manage your contact data from either KDE or WebCit (Figure 9).

Tasks and the Journal are just plain-old work once KCalendar is set up. They don't require any of their own setup.

A lot of other clients support the GroupDAV protocol to varying degrees. Any of these can be used in place of Kontact, albeit likely with less functionality. For a complete list of clients and the status of their GroupDAV support, go to the GroupDAV site (www.groupdav.org/implementations.html).

GroupDAV isn't the only technology that can be used with Citadel. WebDAV and Webcal can be used with clients, such as Mozilla Sunbird and Evolution, to share calendars and schedule events. There is also a Microsoft Outlook connector in the works, but at the moment, Outlook can be used to access only POP/IMAP e-mail and IMAP folders. As time marches on, more and more clients that support GroupDAV and WebDAV come onto the scene. The Citadel FAQ contains a maintained list of clients and how to configure them.

Although a few groupware projects are underway that can give Microsoft Exchange a run for its money, we've found that Citadel is quite simply the easiest to install and maintain. The hardest part of a Citadel install is waiting for all the components to download. Citadel is under active development, and by the time this article prints, a new version may be out. The lead developer, Art Cancro, can be found in the Citadel support on the UNCENSORED! BBS forums (uncensored.citadel.org), along with other Citadel developers and experienced users.