How classical economics fails to comprehend free and open-source software development. And, how it's making a whole new world that's bigger and better for everybody.

At the beach last summer, I caught up with my cousin, Charles Crissman, PhD—a veteran scientist, agricultural economist and Deputy Director General for Research at CIP (better known as the Potato Institute), a large international development organization headquartered in Peru. What surprised and gratified me most was learning from Charles that the results of CIP's research and development are open and accessible. They don't want to see their work benefit one government, or one company, to the exclusion of anybody else, no matter who pays for the work. Agriculturally speaking, they are not in the business of building silos or walled gardens. Instead, they are in the business of helping nature. Literally.

In response, I explained how free software and open-source developers aren't just helping nature, but making it. Their work is creating the core, mantle and crust of a new digital world of code growing within and alongside the physical one. I added that this digital world's geologies are created on NEA principles: Nobody owns it, Everybody can use it, and Anybody can improve it.

“Yes”, he said. “You're talking about pubic goods.” The term public goods intrigued me. But there was no connectivity at the beach, and we really weren't there to discuss economics anyway. So, I did that after I got home.

Public goods are non-rivalrous, it turns out. In other words, they are not scarce. Consuming any of them does not reduce the sum available to others. Wikipedia adds:

The term public good is often used to refer to goods that are non-excludable as well as non-rival. This means it is not possible to exclude individuals from the good's consumption. Fresh air may be considered a public good as it is not generally possible to prevent people from breathing it. However, technically speaking, such goods should be called pure public goods. These are highly theoretical definitions: in the real world there may be no such thing as an absolutely non-rival or non-excludable good, but economists think that some goods in the real world approximate closely enough for these concepts to be meaningful.

Wikipedia also provides a handy way to distinguish public goods from others that differ in excludability or rivalness (Table 1).

Classic Division of Goods in Economy (from Wikipedia)

| Excludability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | ||

| Rivalness | YES | Private good: good: e.g., food, clothing, toys, cars, products subject to value-adds between first sources and final customers | Common pool resource: e.g., sea, rivers, forests, their edible inhabitants and other useful contents |

| Rivalness | NO | Club good: e.g., bridges, cable TV, private golf courses, controlled access to copyrighted works | public good: e.g., law enforcement, national defense, fire fighting, public roads, street lighting |

Wikipedia says, “information goods, such as software development, authorship, and invention” fall in the public good category. Yet it seems that the purpose of free and open-source development is to produce a common pool resource. As Craig Burton has often observed, the idea is to create common infrastructural building material that supports whole industries, rather than just one player in that industry. We do this by making goods that become abundant by being both open and in the public domain.

What we look for is a “because effect”, which is what you get when more money is made because of something than with something. For example, more money is made because of the Internet than with the Internet. Or, in geological terms, more money is made on top of it than inside of it—by many orders of magnitude. Take all the money cable and phone companies make by selling connectivity and transport, then compare that with all the money made on top of that connectivity and transport—that is, because of it. The ratio of the latter to the former is absurdly large.

Yet the Net's carriers (at least in the US) still believe the only Internet business worthy of the label is selling the Net itself. When I talk with folks who work for the carriers, they can barely imagine benefits to their incumbency other than making money every way they can with the Net rather than because of it. Worse, they don't want to see their users doing anything other than consuming services. To them, the Net is nothing more than a pipe between producers and consumers, and their job is to make money by delivering stuff from one to the other. Why is that? Is it just that they are stuck in their ways? Or is there more to the problem than that?

When I talk with economically savvy folks about the goals and effects of free and open-source software—or of the Net itself—I often hear the terms “external”, “externality” and “externalities”. It is not meant in a dismissive way, but rather a positive one. Abundant free software production and use might be seen as a network externality, resulting from the network effects caused by cost-free goods that are easily obtained and used—which is fine. But there is a cost to this perspective. As Wikipedia puts it (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Externalities):

An externality is a side effect from one activity that has consequences for another activity but is not reflected in market prices. Externalities can be either positive, when an external benefit is generated, or negative, when an external cost is generated from a market transaction.

An externality occurs when a decision causes costs or benefits to stakeholders other than the person making the decision, often, though not necessarily, from the use of common goods (for example, a decision that results in pollution of the atmosphere would involve an externality). In other words, the decision-maker does not bear all of the costs or reap all of the gains from his or her action.

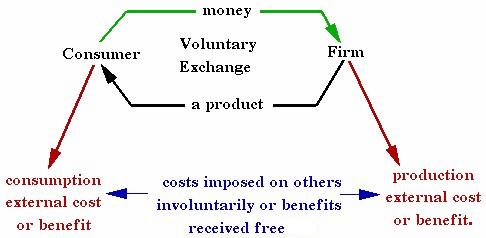

Note the perspective. The view of what's external and what's internal depends on where you stand. And, classical economics stands with transactions between sellers and buyers. The diagram shown in Figure 1 from the same Wikipedia page (on externality) makes the point of view clear.

Figure 1. Externality

Most of us view markets, and economic activity generally, through the prism of transaction. Or, to retain the triangular metaphor, from the top of the pyramid—that is, from the side of the firm, the seller, the producer, the few who sell to the many.

This explains to me why, countless times on the Gillmor Gang podcast, I go silent or into a rant against the “vendor sports” commentary by other Gang members. They see my main area of concern—free and open-source development and DIY activity on the customer's or consumer's side—as external to the work of large producers.

What most of us don't see is that most free and open-source software development isn't in a business at all. It's busy making the stuff that makes the world that everybody lives in. It is pro-business the same way the core of the Earth or the Pacific Ocean is pro-business. Its tides lift all boats, but it is not especially concerned with what any of those boats are up to.

Still, so far we've concerned ourselves only with a few of the many goods economists talk about. Other adjectives modifying goods include durable, non-durable, intermediate, capital, consumer, experience, merit, complement, substitute, scarce, positional and free.

Of all those, the one that best applies to what we're up to is free. Wikipedia explains:

The free good is a term used in economics to describe a good that is not scarce. A free good is available in as great a quantity as desired with zero opportunity cost to society. A good that is made available at zero price is not necessarily a free good. For example, a shop might give away its stock in its promotion, but producing these goods would still have required the use of scarce resources, so this would not be a free good in an economic sense.

There are three main types of free goods:

1) Resources that are so abundant in nature that there is enough for everyone to have as much as he or she wants. An example of this is the air that we breathe.

2) Resources that are jointly produced. Here the free good is produced as a by-product of something more valuable. Waste products from factories and homes, such as discarded packaging, are often free goods (see also dumpster diving).

3) Ideas and works that are reproducible at zero cost, or almost zero cost. For example, if someone invents a new device, many people could copy this invention, with no danger of this “resource” running out. Other examples include computer programs and Web pages.

Not surprisingly, this is consistent with the Free Software Definition (www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html) and Richard M. Stallman's original distinction between free speech (a free good) and free beer (a private good, given away).

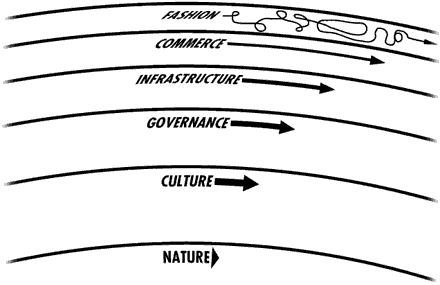

Public infrastructure is a because effect of free software, which is created down at the level of nature—the level where we make the digital world. That level is nicely positioned by the Long Now Foundation in the diagram shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Nature is the level where we make the digital world.

Although this diagram was created to show differences in the speed of change in civilization, it also shows dependencies. Culture depends on nature. Governance depends on culture and nature. Infrastructure depends on all three.

The problem with classical economics is that it centers its concerns at the commerce level, and specifically around transactions. More is involved than just transactions, and a lot of it happens down at these other layers.

Common, public and free goods, whether or not they are produced by commercial activity, are external to it. But, significantly, they are external below, on the supportive side. And you can't completely understand the virtues or natures of those lower-level goods in commercial terms, economic or otherwise—just as the science of mechanics cannot explain physics or chemistry, even as it relies on them.

From the perspective of commerce, it is hard (maybe impossible) to comprehend the supportive (and not merely the external) purposes of free and open-source software—or why they are so deeply supportive of economic activity and value creation. It is hard to see how, by their nature, free and open-source software provide deep and supportive culture, governance and infrastructure for all kinds of commercial activity. Yet this is how, at the deepest level, we are making the digital world.

The big brain-twister is, it only gets larger. That's because, unlike the physical world—with its fixed dimensions and its portfolio of building materials assembled from the periodic table of elements—the digital world can be improved by anybody ready and able to contribute useful code.

That code isn't just in the form of programming, either. It's in the form of text, music, video and other arts that contribute to common understanding. Here is where we are only beginning to develop the culture and governance that will support new social infrastructures, including those of government and business.

Wikipedia is a perfect example. I'll be curious to see how the entries on economics that served as sources for this column will change as readers of Linux Journal (and other instruments of understanding) make corrections and improvements.

In the old pre-digital world, about all we could do was consume and complain. Now we can produce and construct. And that makes a world of difference.