Understanding work-load averages as opposed to CPU usage.

Many Linux administrators and support technicians regularly use the top utility for real-time monitoring of their system state. In some shops, it is very typical to check top first when there is any sign of trouble. In that case, top becomes the de facto critical measurement of the machine's health. If top looks good, there must not be any system problems. top is rich with information—memory usage, kernel states, process priorities, process owner and so forth all can be obtained from top. But, what is the purpose of those three curious load averages, and what exactly are they trying to tell me? To answer those questions, an intuitive as well as a detailed understanding of how the values are formed are necessary. Let's start with intuition.

The three load-average values in the first line of top output are the 1-minute, 5-minute and 15-minute average. (These values also are displayed by other commands, such as uptime, not only top.) That means, reading from left to right, one can examine the aging trend and/or duration of the particular system state. The state in question is CPU load—not to be confused with CPU percentage. In fact, it is precisely the CPU load that is measured, because load averages do not include any processes or threads waiting on I/O, networking, databases or anything else not demanding the CPU. It narrowly focuses on what is actively demanding CPU time. This differs greatly from the CPU percentage. The CPU percentage is the amount of a time interval (that is, the sampling interval) that the system's processes were found to be active on the CPU. If top reports that your program is taking 45% CPU, 45% of the samples taken by top found your process active on the CPU. The rest of the time your application was in a wait. (It is important to remember that a CPU is a discrete state machine. It really can be at only 100%, executing an instruction, or at 0%, waiting for something to do. There is no such thing as using 45% of a CPU. The CPU percentage is a function of time.) However, it is likely that your application's rest periods include waiting to be dispatched on a CPU and not on external devices. That part of the wait percentage is then very relevant to understanding your overall CPU usage pattern.

The load averages differ from CPU percentage in two significant ways: 1) load averages measure the trend in CPU utilization not only an instantaneous snapshot, as does percentage, and 2) load averages include all demand for the CPU not only how much was active at the time of measurement.

Authors tend to overuse analogies and sometimes run the risk of either insulting the reader's intelligence or oversimplifying the topic to the point of losing important details. However, freeway traffic patterns are a perfect analogy for this topic, because this model encapsulates the essence of resource contention and is also the chosen metaphor by many authors of queuing theory books. Not surprisingly, CPU contention is a queuing theory problem, and the concepts of arrival rates, Poisson theory and service rates all apply. A four-processor machine can be visualized as a four-lane freeway. Each lane provides the path on which instructions can execute. A vehicle can represent those instructions. Additionally, there are vehicles on the entrance lanes ready to travel down the freeway, and the four lanes either are ready to accommodate that demand or they're not. If all freeway lanes are jammed, the cars entering have to wait for an opening. If we now apply the CPU percentage and CPU load-average measurements to this situation, percentage examines the relative amount of time each vehicle was found occupying a freeway lane, which inherently ignores the pent-up demand for the freeway—that is, the cars lined up on the entrances. So, for example, vehicle license XYZ 123 was found on the freeway 30% of the sampling time. Vehicle license ABC 987 was found on the freeway 14% of the time. That gives a picture of how each vehicle is utilizing the freeway, but it does not indicate demand for the freeway.

Moreover, the percentage of time these vehicles are found on the freeway tells us nothing about the overall traffic pattern except, perhaps, that they are taking longer to get to their destination than they would like. Thus, we probably would suspect some sort of a jam, but the CPU percentage would not tell us for sure. The load averages, on the other hand, would.

This brings us to the point. It is the overall traffic pattern of the freeway itself that gives us the best picture of the traffic situation, not merely how often cars are found occupying lanes. The load average gives us that view because it includes the cars that are queuing up to get on the freeway. It could be the case that it is a nonrush-hour time of day, and there is little demand for the freeway, but there just happens to be a lot of cars on the road. The CPU percentage shows us how much the cars are using the freeway, but the load averages show us the whole picture, including pent-up demand. Even more interesting, the more recent that pent-up demand is, the more the load-average value reflects it.

Taking the discussion back to the machinery at hand, the load averages tell us by increasing duration whether our physical CPUs are over- or under-utilized. The point of perfect utilization, meaning that the CPUs are always busy and, yet, no process ever waits for one, is the average matching the number of CPUs. If there are four CPUs on a machine and the reported one-minute load average is 4.00, the machine has been utilizing its processors perfectly for the last 60 seconds. This understanding can be extrapolated to the 5- and 15-minute averages.

In general, the intuitive idea of load averages is the higher they rise above the number of processors, the more demand there is for the CPUs, and the lower they fall below the number of processors, the more untapped CPU capacity there is. But all is not as it appears.

The load-average calculation is best thought of as a moving average of processes in Linux's run queue marked running or uninterruptible. The words “thought of” were chosen for a reason: that is how the measurements are meant to be interpreted, but not exactly what happens behind the curtain. It is at this juncture in our journey when the reality of it all, like quantum mechanics, seems not to fit the intuitive way as it presents itself.

The load averages that the top and uptime commands display are obtained directly from /proc. If you are running Linux kernel 2.4 or later, you can read those values yourself with the command cat /proc/loadavg. However, it is the Linux kernel that produces those values in /proc. Specifically, timer.c and sched.h work together to do the computation. To understand what timer.c does for a living, the concept of time slicing and the jiffy counter help round out the picture.

In the Linux kernel, each dispatchable process is given a fixed amount of time on the CPU per dispatch. By default, this amount is 10 milliseconds, or 1/100th of a second. For that short time span, the process is assigned a physical CPU on which to run its instructions and allowed to take over that processor. More often than not, the process will give up control before the 10ms are up through socket calls, I/O calls or calls back to the kernel. (On an Intel 2.6GHz processor, 10ms is enough time for approximately 50-million instructions to occur. That's more than enough processing time for most application cycles.) If the process uses its fully allotted CPU time of 10ms, an interrupt is raised by the hardware, and the kernel regains control from the process. The kernel then promptly penalizes the process for being such a hog. As you can see, that time slicing is an important design concept for making your system seem to run smoothly on the outside. It also is the vehicle that produces the load-average values.

The 10ms time slice is an important enough concept to warrant a name for itself: quantum value. There is not necessarily anything inherently special about 10ms, but there is about the quantum value in general, because whatever value it is set to (it is configurable, but 10ms is the default), it controls how often at a minimum the kernel takes control of the system back from the applications. One of the many chores the kernel performs when it takes back control is to increment its jiffies counter. The jiffies counter measures the number of quantum ticks that have occurred since the system was booted. When the quantum timer pops, timer.c is entered at a function in the kernel called timer.c:do_timer(). Here, all interrupts are disabled so the code is not working with moving targets. The jiffies counter is incremented by 1, and the load-average calculation is checked to see if it should be computed. In actuality, the load-average computation is not truly calculated on each quantum tick, but driven by a variable value that is based on the HZ frequency setting and tested on each quantum tick. (HZ is not to be confused with the processor's MHz rating. This variable sets the pulse rate of particular Linux kernel activity and 1HZ equals one quantum or 10ms by default.) Although the HZ value can be configured in some versions of the kernel, it is normally set to 100. The calculation code uses the HZ value to determine the calculation frequency. Specifically, the timer.c:calc_load() function will run the averaging algorithm every 5 * HZ, or roughly every five seconds. Following is that function in its entirety:

unsigned long avenrun[3];

static inline void calc_load(unsigned long ticks)

{

unsigned long active_tasks; /* fixed-point */

static int count = LOAD_FREQ;

count -= ticks;

if (count < 0) {

count += LOAD_FREQ;

active_tasks = count_active_tasks();

CALC_LOAD(avenrun[0], EXP_1, active_tasks);

CALC_LOAD(avenrun[1], EXP_5, active_tasks);

CALC_LOAD(avenrun[2], EXP_15, active_tasks);

}

}

The avenrun array contains the three averages we have been discussing. The calc_load() function is called by update_times(), also found in timer.c, and is the code responsible for supplying the calc_load() function with the ticks parameter. Unfortunately, this function does not reveal its most interesting aspect: the computation itself. However, that can be located easily in sched.h, a header used by much of the kernel code. In there, the CALC_LOAD macro and its associated values are available:

extern unsigned long avenrun[]; /* Load averages */

#define FSHIFT 11 /* nr of bits of precision */

#define FIXED_1 (1<<FSHIFT) /* 1.0 as fixed-point */

#define LOAD_FREQ (5*HZ) /* 5 sec intervals */

#define EXP_1 1884 /* 1/exp(5sec/1min) as fixed-point */

#define EXP_5 2014 /* 1/exp(5sec/5min) */

#define EXP_15 2037 /* 1/exp(5sec/15min) */

#define CALC_LOAD(load,exp,n) \

load *= exp; \

load += n*(FIXED_1-exp); \

load >>= FSHIFT;

Here is where the tires meet the pavement. It should now be evident that reality does not appear to match the illusion. At least, this is certainly not the type of averaging most of us are taught in grade school. But it is an average nonetheless. Technically, it is an exponential decay function and is the moving average of choice for most UNIX systems as well as Linux. Let's examine its details.

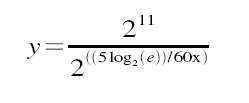

The macro takes in three parameters: the load-average bucket (one of the three elements in avenrun[]), a constant exponent and the number of running/uninterruptible processes currently on the run queue. The possible exponent constants are listed above: EXP_1 for the 1-minute average, EXP_5 for the 5-minute average and EXP_15 for the 15-minute average. The important point to notice is that the value decreases with age. The constants are magic numbers that are calculated by the mathematical function shown below:

When x=1, then y=1884; when x=5, then y=2014; and when x=15, then y=2037. The purpose of the magical numbers is that it allows the CALC_LOAD macro to use precision fixed-point representation of fractions. The magic numbers are then nothing more than multipliers used against the running load average to make it a moving average. (The mathematics of fixed-point representation are beyond the scope of this article, so I will not attempt an explanation.) The purpose of the exponential decay function is that it not only smooths the dips and spikes by maintaining a useful trend line, but it accurately decreases the quality of what it measures as activity ages. As time moves forward, successive CPU events increase their significance on the load average. This is what we want, because more recent CPU activity probably has more of an impact on the current state than ancient events. In the end, the load averages give a smooth trend from 15 minutes through the current minute and give us a window into not only the CPU usage but also the average demand for the CPUs. As the load average goes above the number of physical CPUs, the more the CPU is being used and the more demand there is for it. And, as it recedes, the less of a demand there is. With this understanding, the load average can be used with the CPU percentage to obtain a more accurate view of CPU activity.

It is my hope that this serves not only as a practical interpretation of Linux's load averages but also illuminates some of the dark mathematical shadows behind them. For more information, a study of the exponential decay function and its applications would shed more light on the subject. But for the more practical-minded, plotting the load average vs. a controlled number of processes (that is, modeling the effects of the CALC_LOAD algorithm in a controlled loop) would give you a feel for the actual relationship and how the decaying filter applies.