An easy Web-based captive Wi-Fi portal is great for users. A Web-based captive portal system that fits on a Linksys box is great for administrators too.

It has become commonplace for most major cities to have a Wi-Fi group. The Wireless Community movement has spread across North America, Europe and has extended to Latin America and Asia. Hackers world-wide haven't been able to keep their hands off low-cost, easily extensible hardware. Some Wi-Fi groups get together and share technical information and war-driving data, and other groups work on projects setting up ad hoc mesh networks or creating free hotspots in their favorite hangouts.

Two years ago, in an event similar to what has taken place in many other cities, a group of Montréal technology enthusiasts got together and decided to start creating free hotspots for themselves and for other Montréalers. People joined the group after hearing about it through the local open-source grapevine. Calling themselves Ile Sans Fil (French for “Wireless Island”—and, yes, Montréal is an island), they are now one of the more active established Wi-Fi groups in the world, with 25–35 active volunteers, 50 hotspots and 6,000 users. Their current rate of expansion is 4–8 hotspots and 1,000 users per month. Based on the number of users, this volunteer group is the most successful of the seven Wi-Fi companies operating in that area.

Ile Sans Fil (ISF, www.ilesansfil.org) was able to get a quick start on the project by using a popular open-source captive portal called NoCat, which did a good job of allowing only users from a list of user names and passwords through. A captive portal is a dynamic firewall in which all traffic is blocked until the user logs in (or a disclaimer page was displayed and terms of service were agreed to). The login page works by intercepting http traffic and, in its place, displaying a form until the user is validated. Once logged in, some, or all, ports work normally. By nature, all captive portal authentication solutions are vulnerable to MAC address spoofing, and as such, these are not bulletproof. However, they have the huge advantage of not requiring any software beyond a Web browser to perform sign-on.

But NoCat wasn't perfect for their needs. The NoCat gateway was a Perl script that relied on several heavy packages. It was too big to run on most embedded hardware, so the choice was either to run it on new machines (possibly the small but expensive Soekris board) or to use old desktops dug out of closets and storage areas. Although inexpensive, the result was an open wireless access point connected to a Pentium I connected to a modem and a WAP (wireless access point). Keeping a network of heterogeneous secondhand Pentium Is running in public places proved to be a support nightmare, even for the initial three or four hotspots. The NoCat central server also lacked any network monitoring features, it was difficult to get any useful statistics from its logs and it didn't feature any mechanisms to serve different content for each hotspot. Finally, to keep a user's connection alive, NoCat used a second browser window that used JavaScript to ping the gateway every five minutes. This meant that devices that couldn't open more than one window (such as PDAs) or that had no (or disabled) JavaScript support were forced to re-authenticate continuously.

Fortunately, two years ago a wireless router running Linux became available (the Linksys WRT54G). It wasn't advertised as running Linux, but the Seattle Wireless group discovered this, and the hacking began. ISF finally had an inexpensive embedded platform to move to. They chose OpenWRT as a distro, but NoCat and its dependencies just wouldn't fit.

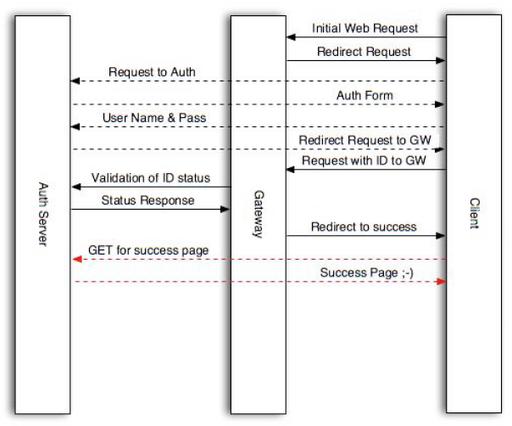

Figure 1. Wifidog has two parts: a central authentication server and a gateway located at each wireless hotspot.

And so the Wi-Fi Guard Dog captive portal system was born. Like NoCat, Wifidog (www.wifidog.org) consists of two parts: a gateway per hotspot running a client process and a Web-based central server (Figure 1).

The Wifidog gateway is written in C with no dependencies beyond the kernel. A working gateway install can be packaged in less than 15Kb on an i386 platform. It works well on the MIPS-based WRT54G running OpenWrt. The Wifidog central server is written in PHP and handles authentication and manages the network. The system knows which hotspots are up through heartbeating from the gateway.

The gateway remains small and simple by delegating all cryptography to the user's Web browser and the auth server. Tokens are generated by the auth server upon successful authentication and are then sent to the gateway. The gateway then validates the token with the auth server. Tokens are revalidated periodically in case they expire.

How secure is it? The gateway never sees the password. The token itself is transmitted in the clear between the gateway and the auth server. It would be quite simple to encrypt this, but it has been deemed unnecessary bloat, considering that it's a one-time-use token and that to do a man-in-the-middle attack on it, an attacker needs to be between the gateway and the auth server, in which case the attacker already has Internet access, making the whole attack pointless. A much more realistic attack is MAC address spoofing, which is inherently easy to do with any captive portal software running on an open Wi-Fi network. The only solution for this is to use WPA. Unfortunately, tech-support realities make it completely unrealistic to require this until every platform has a central place to enter the necessary information (not to mention that many drivers still don't support it). The team will eventually move toward 802.11i once support for the standard improves.

Of course, the Wifidog auth server handles user authentication (currently, plugins exist for internal authentication and for authenticating to a remote radius database, including logging the amount of traffic transfered by each client). But the auth server does much more than that. It handles user sign-up, real-time network monitoring, extensive statistics about network usage patterns and hotspot popularity.

With Wifidog, the volunteer group had an easy way to continue deploying hotspots while minimizing the time spent on support.

However, although this technically has been a successful project in creating another open-source captive portal solution, it is only half the story. From the beginning, ISF viewed setting up free hotspots as only a first step. The volunteers now had the tools to draw laptop users from their basements and home offices into public spaces. The next step of the project was to use the network of hotspots to help create a sense of local community.

One way in which that is done is through the promotion of local content. A unique feature of the Wifidog system is its extensive support for location-specific content. Users connecting from Café Laika see an entirely different splash page and portal page than users connecting from Atwater Library. At first, the only form that local content took was HTML and RSS feeds tied to a hotspot. Fortunately, some of the hotspots had their own RSS feeds from their Web sites.

Through working with a local new media arts group, the local content feature recently was extended, so that now there is a system that also can manage text, images, audio, video and photos from Flickr (by using the Flickr API). All of this content can be sent across the network or sent only to select hotspot portals. The extensive logging functions also allow the group to show content to a user only once, only once per hotspot, once per day. It has certainly allowed these artists some interesting and unique possibilities for location-based art.

Another feature is the ability to see who else is on-line at a hotspot (either locally or remotely) and find out more about them if they have filled out their profile. Profiles are an opt-in feature and not only because the group doesn't want to annoy its users. The geographical proximity of users (in the same hotspot) raises certain safety and privacy issues that don't exist in most instances of social-networking software.

Figure 2. Developers have been happy to see Wifidog adopted worldwide. From left to right: Philippe April, Pascal Leclerc, Alexandre Carmel-Veilleux, François Proulx and Benoit Grégoire. Not shown: Mina Naguib.

This past summer has been gratifying for the developers as their project has drawn the eyes of many wireless groups all over the world. Among the groups adopting it are WirelessLondon, New York City Wireless and Paris Sans Fil. WirelessLondon has recently started to use the Wifidog gateway with their existing central server. Jo Walsh—member of the group and co-author of the recent O'Reilly book Mapping Hacks—writes, “We found it easy to customize for our needs; we adapted our portal service to it in half an hour. The presence of an active and committed development community around Wifidog is reassuring; we know it won't go away, and the community's been gracefully receptive to our suggestions.”

Dana Spiegel—the executive director of NYCwireless—talks about his organization's impending trial of the captive portal, “NYCwireless is using the software in a pilot project and hopes to deploy it by the end of the summer to help local hotspots showcase local talent, multimedia sharing, art and student works. [Wifidog] is a great collaborative effort to provide a useful solution for community wireless networks. It enables the creation of a supported wireless network with community-oriented and created content, and really demonstrates how these networks and groups provide an important service to local areas.”

The group has not been surprised by the success. Benoit Grégoire, one of the lead developers of the group, says, “We designed Wifidog to be the Swiss Army knife of captive portal systems. We hoped that it could meet the needs of most wireless community groups well enough that they would prefer to help with its development rather than roll their own. Now we're seeing some of the realization of that goal.” The world of Wi-Fi community groups is starting to agree with them. What remains a question is how these other groups will use Wifidog for their own networks and in their own communities. From finding ways to make the software work (and make sense) in a mesh network, to developing GIS applications, to adding chat functionality to the network, there's lots of promising community and social applications for what was originally an infrastructure project.

Beyond the interesting technical possibilities, it is the chance to have an impact on the lives of their fellow citizens that seems to motivate Wifidog developers the most. With 10,000 users expected by December 2005 in Montréal alone, there is a good chance that their code will be used by neighbors, coworkers and friends. That, combined with the frequent press coverage and the chance to work with people they wouldn't normally meet, such as artists and community activists, means the team's energy and enthusiasm should remain high for the foreseeable future.