The heart of your Linux recording studio is the hard-disk recorder. Get started with Ardour, which brings pro recording features to open source.

Contemporary musicians employ the computer as a digital audio workstation (DAW) to perform a wide variety of tasks dealing with sound. Typical uses include recording and editing soundfiles, adding effects and dynamics processing and preparing audio tracks for a CD master disc.

The centerpiece of the modern musician's computer-based studio is the hard-disk recorder (HDR). Musicians working on Apple or Microsoft Windows machines have an impressive selection of HDR systems to choose from, but until recently Linux users have had nothing truly comparable for professional work. A professional-quality HDR is a profoundly nontrivial programming endeavor, and proprietary HDR developers have provided little technical guidance for would-be designers of an open-source DAW.

Today, thanks to the talent and perseverance of chief designer/programmer Paul Davis and his talented crew, Linux musicians now have a native-born professional-quality HDR/DAW, named Ardour.

Ardour is a multitrack recording and editing system for high-quality digital audio. Ardour supports audio processing plugins (LADSPA and VST), parameter control automation, sophisticated panning control and many advanced editing procedures. Recognized synchronization protocols include MIDI time code (MTC), a means of encoding SMPTE time code to MIDI; MIDI machine control (MMC), a set of MIDI messages for controlling transport features of hardware mixers and recorders; and JACK, a low-latency audio server and application transport control interface for Linux and Mac OS X.

Figure 1. Ardour is a multitrack recording and editing system that supports consumer and professional audio hardware.

Professional audio recording hardware supports datatypes not commonly encountered in consumer-grade systems. A pro DAW can handle audio at greater bit depth, for deeper amplitude range and precision; at high sampling rates, for more accurate frequency resolution; and with greater flexibility in sound location and spatialization. It is not uncommon for professional recordists to work with 32-bit soundfiles recorded with a sampling rate of 96kHz, more than twice the resolution of compact disc audio.

Ardour is not a MIDI sequence recorder or editor. It knows nothing about music notation, and it is not designed to be a soundfile editor. Ardour has only a few built-in signal processing capabilities, and most of its processing power comes from its supported plugins. Finally, Ardour does not directly provide facilities for CD mastering and burning, but it is designed to work well with the excellent JAMin mastering suite.

The extent of your use of Ardour is limited fundamentally by the capabilities of your hardware. If a sound card or audio board is supported by the ALSA sound system, it should work with Ardour; however, standard consumer-grade audio devices are not suitable for using Ardour to its full extent. You can do great things with Ardour and a SoundBlaster Live, but for professional work, Ardour is happiest with a multichannel digital audio interface, such as the RME Hammerfall and M-Audio Delta cards.

Do your homework before purchasing your audio interface. Check the ALSA site for up-to-date news regarding supported systems, and try to find others who can comment on the suitability of a particular card. Ardour can respond to MIDI parameter control, so study the MIDI implementation charts for any external equipment you plan to use. See if your mixer specifications support MMC or MTC. Ardour is designed to work with automated mixer control surfaces, but again, your equipment has to support the features.

The question of a sufficient base computer system often pops up on the Ardour users mailing list. Satisfactory results have been reported with a 500MHz CPU, but such a system is too limiting for professional use. A fast CPU ensures accurate synchronization while recording or playing multiple audio tracks, and it is absolutely necessary if you intend to use many effects. For example, a good reverberation effect can be intensely CPU-hungry. You also should have a large, fast hard disk, properly tuned with the hdparm utility for maximum performance. Multiple tracks of streaming audio data absolutely require a powerful CPU and a fast hard disk to ensure perfect synchronization. Also, 32-bit digital audio files can be huge, and a typical recording session can create nontrivial storage demands. For professional use, you are advised to equip your system with two disks—one for your system and application software and one dedicated only to session audio storage. The Ardour Web site offers suggestions for specific CPUs, hard-disk specifications and even recommended motherboards. For best results with Ardour, follow the designer's advice.

Aaron Trumm's excellent article “The Linux-Based Recording Studio” [Linux Journal, May 2004] describes room considerations and the setup and configuration of external equipment needed for serious recording. Rather than rehashing Aaron's recommendations, I simply refer readers to that article for advice on selecting microphones, mixers, monitor speakers and other outboard gear.

The current public version of Ardour is available as source code. Packages are available for various Linux distributions, including Red Hat/Fedora, Mandrake, Debian and Slackware; see the on-line Resources. CVS access is selective at this time, but a nightly tarball is available from the Ardour Web site. Compiling Ardour from its source code is uncomplicated, and complete instructions are included with the tarball.

Check the Ardour Web site for the latest support software required to build and install the program. Ardour's dependencies include up-to-date installations of the ALSA kernel sound system, the JACK audio server, the LADSPA plugin API and collections and various other audio-related software components. You can configure your existing Linux installation for optimal performance with the program, but if you're serious about using Ardour you are advised to install an audio-optimized system such as AGNULA/Demudi, a Debian-based distribution, or Planet CCRMA, Red Hat/Fedora packages. Slackware users should install Luke Yelavich's AudioSlack packages, and Mandrake users can find all necessary packages at Thac's site.

JAMin is a suite of post-production audio utilities designed for the preparation of tracks destined for burning to a master CD. This mastering process uses tools such as compressors, equalizers and limiters to reduce frequency and amplitude imbalances between tracks. If you plan to record a full CD with Ardour, you should plan on mastering it with JAMin.

Any modern HDR performs three basic functions, corresponding to the typical work-flow stages of recording, editing and mixing digital audio. Each stage can be quite complex within itself, but Ardour's user interface sensibly organizes the program's complexities.

Ardour records to the available hardware limits. If your audio interface supports 32-channel I/O and there's an ALSA driver for it, you should be able to work with 32 simultaneous audio channels. Assignment of channels to tracks is completely flexible, and each track supports mono or stereo input. Ardour's synchronization capabilities currently work best with JACK-compliant applications, such as the Hydrogen drum machine and Rosegarden audio/MIDI sequencer. Much work, however, is going into improving support for MIDI time code.

As mentioned above, Ardour is not a soundfile editor, but it does include a variety of edit processes optimized for multitrack recording, such as typical and not-so-typical cut/copy/paste operations, grouped track editing and fine control over track and segment relocation. Ardour offers its own time stretching and amplitude normalization, but the bulk of its processing power comes from LADSPA plugins.

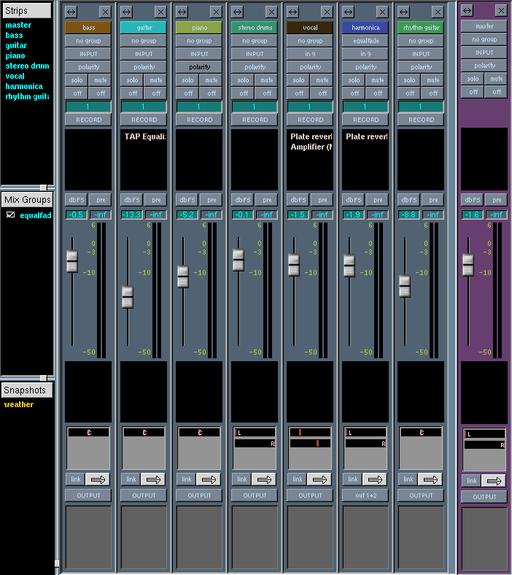

Ardour's mixer panel presents a series of per-track fader strips and a master control strip. A track strip is divided into sections corresponding to a “from the top downward” data path. Input begins at the top of the strip and passes through controls such as signal polarity and track solo/mute status. It moves on through pre-fader plugins, the track fader itself and post-fader plugins before reaching its pan position and heading out to the output or outputs, typically but not always a master bus. Other notable features of Ardour's mixer include gain automation, record and playback fader movement; MIDI control to and from mixers with MIDI machine control; and plugin parameter control automation.

Figure 3. In the Mixer panel, think of audio data moving from the top down through each track strip.

Thanks to Ardour's use of Erik de Castro Lopo's sndfile library, you can import and export audio data (track, region and session) to and from Ardour in any format supported by libsndfile. Currently, that's about 20 different audio file types, including the most popular consumer-grade and professional formats.

My goal in the following example session is to demonstrate how Ardour functions as a multitrack recording system. I've tried to keep technical terminology to a minimum, but this article does not intend to be a primer for digital recording. Basic information on the subject can be found at www.homerecording.com, while more advanced topics are covered at www.prorec.com. Many other on-line and hard-copy resources can be found with relevant searches on Google and Amazon.

Session hardware included an M-Audio Delta 66 digital audio interface, a system that includes a PCI card and a breakout box that together provide 4×4 analog I/O and 2×2 digital I/O. The digital ports can be configured for either S/PDIF, a high-quality consumer-grade digital I/O or AES/EBU, a standard for the recording industry. Each input point is a stereo port, effectively giving me a possible total of 12 input channels, with far more flexible routing than is possible with a consumer-grade, stereo-only sound card.

I employed two external mixers for the session. A Yamaha DMP11 was used as a submixer for external synthesizers, and I used a Tascam TM-D1000 for mixing vocal, guitar and harmonica performances before sending them to the Delta 66. The Tascam mixer provides S/PDIF digital output, so I routed its feed to the digital ports of the Delta card.

My plan was to use Ardour to record an original song, with multiple instrumental and vocal tracks, and mix it to recreate the sound of a small group playing live. However, in this session the small group is only me, with some imported WAV files and some multitracking in Ardour. I also planned to use a few LADSPA plugins to add effects to some of the tracks and to use Ardour's pan controls to position my tracks across the stereo audio panorama, as players would be positioned on a stage.

I used a MIDI sequencer to create parts for piano, bass, guitar and drums. I saved each part as a MIDI file and converted them all to WAV audio files with the popular TiMidity MIDI utility. The drum track was converted to a stereo file, the others were converted to monaural files and all the files were created in 16-bit 44.1kHz WAV format. At that point they were ready for importing to Ardour.

When you open Ardour for the first time, you see an empty track display complete with a kindly reminder that you need to create an Ardour session by using the Session/New dialog. Session templates are available, but I knew my immediate track needs and created a custom track layout—one stereo and four mono tracks. I imported my WAV files into those tracks, and there was my backing band.

Next, I recorded three more tracks in Ardour itself, adding a rhythm guitar part, the vocal track and a harmonica solo. Recording in Ardour is simple: click on the R button in your selected track to arm it for recording and then set your inputs and levels in the track's mixer strip. Next, click on the main display's big red Record button, click on the transport play control and record at will. You can monitor some or all other tracks, muting and soloing tracks and groups of tracks in real time for testing different ensembles.

When I was happy with the recorded performances, I started working on the mix. Many aspects of the raw mix were in need of attention: the rhythm guitar track needed a volume fade-out at the end and equalization (EQ) throughout, the MIDI instruments weren't bright enough in the mix and everything needed to be normalized and balanced. Fortunately, Ardour handled these tasks with the greatest of ease. I used LADSPA plugins for equalization and amplification, and I employed Ardour's own internal normalization routine when it was needed. I also added reverb to the vocal and harmonica parts, again by using a LADSPA plugin.

Adding the fade-out to my rhythm guitar track proved to be an interesting task. First, I clicked on the track's automation button to set the automation curve display, and then with the mouse on the Gain mode button I could draw the amplitude curve. Then, I discovered that I could use Ardour's control automation in the mixer as well. I set the automation state to write, and then I played the section to be faded out and reduced the fader level. Ardour recorded my adjustments to the fader, I reset the automation status to play, and the fader moved downward automatically on playback. By the way, faders can be ganged together as a mix group for simultaneous operation, including the recording of simultaneous automation curves.

So how did all this creative activity turn out? You can hear the results for yourself; see Resources for the URL.

Bear in mind that the recording has not yet been mastered, and I still can return to my original session and make other changes. Feel free to suggest improvements, but try to be kind about my modest efforts.

Paul Davis also is responsible for creating the JACK low-latency audio server and transport control interface, so you would expect Ardour's JACK synchronization capabilities to be well evolved. I tested the Hydrogen drum machine and the Rosegarden sequencer running in JACK master and slave modes and experienced mixed levels of success. Both programs were synced to and from Ardour by way of JACK without trouble. Hydrogen got along nicely with Ardour, but I had problems recording the output of softsynths driven by Rosegarden. The Rosegarden team is aware of this issue and intends to resolve it, but you should check the Rosegarden Web site for the latest news.

At the time of these tests, Ardour's support for MTC send/receive was under heavy revision, so I was unable to complete any meaningful tests. However, MTC support is a major item on many Ardour users' wishlists, and the remaining bugs should be worked out before version 1.0 is released. Other means of synchronization may be supported in future versions of Ardour. Direct SMPTE reading, MIDI clock and SPP (song position pointer) have been suggested as likely candidates, but work on those protocols will have to wait until after the Ardour 1.0 release.

As I learn more about Ardour, there seems to be even more to learn. It's a credit to Ardour's designers that the initial interface view is clear and uncluttered, using pull-down and pop-up menus to reveal many underlying features. Also, many helpful keyboard bindings exist, but you need to run ardour -b at the command prompt in an xterm to discover them.

After gaining more confidence with Ardour's basic features, I started to explore more of its capabilities. The TM-D1000 sends MIDI messages and controller streams for most of its actions, and Ardour's controls can be bound to external MIDI control surfaces. Ctrl-middle-click on a button or fader and then activate the controller to set the binding. This feature is very cool, allowing any hardware device that sends MIDI controller streams to act as a control surface for Ardour. Incidentally, group definitions still are in effect, so you can control multiple faders in Ardour from a single external fader.

The TM-D1000 also transmits and responds to MIDI machine control (MMC) commands, a valuable feature because Ardour can control and be controlled from such a device. MMC messages include typical transport control actions such as start/stop, fast-forward and rewind. Thus, a MIDI-sensible mixer such as the TM-D1000 can function as a hardware control surface for almost all of Ardour's operations.

In an article of this length I could test only the features most relevant to my goals. I have not worked yet with Ardour's looping mechanisms, MTC still was stabilizing as I completed this article, I didn't check out the timestretch capability and so on. As I said, Ardour is a deep application, and there are many useful and interesting features not touched on in this article's use of the program.

Development activity around Ardour is intense, especially as the program closes in on its 1.0 release. Many people are interested in a viable alternative to the proprietary lock-in solutions available for other operating systems, and Ardour appears to moving along the right development path. Much work remains to be done, including improved MIDI capabilities, video track support, expanded synchronization possibilities and a GUI overhaul (GTK2 support is planned). However, Ardour currently is in a feature-freeze, with bug fixes and stability being the first order of the day before version 1.0 is released.

As might be expected in a pre-1.0 beta release of a large-scale complex project, it is not quite bug-free. Ardour's Mantis bug-tracking and feature-request system provides an excellent way to check on the status of known problems, report new ones and make suggestions for future releases.

VST plugin support currently is problematic, due mainly to continuing changes in WINE and Linux kernel development, but it is a high-priority item for the developers. Many users have expressed their willingness to switch platforms for their audio work if VST/VSTi support becomes seamless under Linux.

Ardour's documentation is another lively issue, because currently there is no official users' manual. It is likely that Paul Davis will continue to make Ardour freely available while charging a fee for a high-quality manual. Meanwhile, users unfamiliar with the basic design concepts of a hard-disk recorder are advised to retrieve and study manuals for proprietary DAWs, such as Pro Tools or Cubase. Some Ardour-specific documentation can be found in the source package text files and in various on-line resources, such as the Quick Toots series (see Resources), and in the traffic on the ardour-users and ardour-dev mail lists. Developers and testers also communicate on the #ardour IRC channel, while normal users carry on considerable discussion of Ardour-related matters on the mail lists for AGNULA/Demudi, Planet CCRMA, ALSA and the Linux Audio Users group.

Is Ardour ready for the big time? Perhaps not quite yet, but its road map is clearly headed there, and the remaining trip won't take long. I believe that it will be only a short time before Ardour starts raising eyebrows in the mainstream commercial audio software world. Ardour already has been used to record and mix entire CD projects, and more users are reporting success with Ardour in their own recording projects. I expect to be making a lot more music with Ardour. Feel free to stop by my site and check the occasional results.

The author sends vast thanks and appreciation to Paul Davis, Taybin Rutkin, Jesse Chappell, Steve Harris and all the other members of the Ardour development crew. Their work on Ardour, and so many other valuable Linux audio projects, truly is innovative and indeed a labor of love. The free musicians of the world salute you!

Major thanks also go to the members of the Ardour users mail list, especially Jan Depner, Mark Knecht, Aaron Trumm and Josh Karnes. Developers and users all were helpful as I found my bearings in some of Ardour's trickier places, proving that good company does indeed lessen the difficulties.

Resources for this article: www.linuxjournal.com/article/7969.