Developing a new generation of wireless communications means you need FPGA development tools, a cluster for simulation and an embedded OS for prototype devices. Linux fits the need.

Here at Tait Electronics Group Research in Christchurch, New Zealand, we quietly have been building an advanced wireless networking concept called space-time (ST) processing. ST is predicted by many to drive the next big-step improvement in wireless technology after 3G. The nature of space-time is that the mathematics behind it and, consequently, its implementation, are extremely complex. Many academic researchers are working on this, but we have completed two world-first practical implementations on our ST array research (STAR) platform. These are time-reversal space-time block coding (TR-STBC) and the tongue-twisting single carrier, adaptive multivariate decision feedback equalised multiple-in, multiple-out (SC-AMV-DFE-MIMO) coding scheme. Without a doubt, these achievements were possible largely thanks to the performance and adaptability of Linux.

This article describes how Linux was key in enabling our mathematical simulations and was adopted for our embedded processing and runtime control. We cover such diverse aspects as message passing interface (MPI), cluster computing, embedded Linux, PHP, shell scripts, network filesystem (NFS), SMB (server message block) and kernel modules on ARM, Alpha and Intel architecture computers. We skip development details, but describe the system as it operates today, highlighting some of the real advantages we gained by using Linux.

In its basic configuration, each STAR platform consists of one multichannel transmitter unit and one multichannel receiver unit, both connected to a shared LAN and transmitting anything up to around 200Mb/s at microwave frequencies. There actually are 23 printed circuit boards in each unit, which took 15 people a year to design and build.

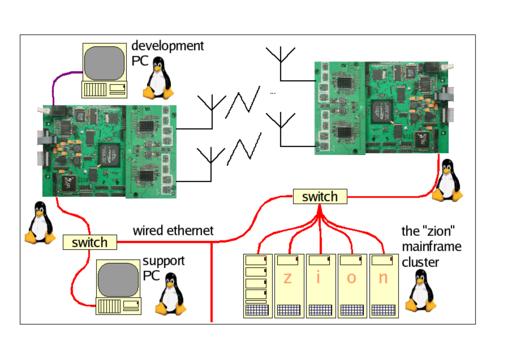

Figure 1. A bidirectional RF link uses one multichannel transmitter and one multichannel receiver on each STAR platform.

Figure 1 shows the system wired to a shared Ethernet as a bidirectional RF link. The setup shown is for experimental purposes; an actual product would not have a shared Ethernet between transmitter and receiver.

All of the clever radio processing is done on the digital board, not by the ARM processor but by a dedicated field programmable gate array (FPGA) and digital signal processor (DSP). We call FPGA code firmware because we can't decide whether it's software or hardware; this way we don't have to comply with either the software coding standards or the hardware design standards of the company. In the middle of last year, when we designed the system, we used the biggest, fastest and most expensive FPGA and DSP we could obtain, and we since have added two more big FPGAs. The ARM is not used for low-level processing because we require over 50,000MIPS for ST processing. With this complexity, even the fastest components alone are not enough, so we decided early on to build a multiprocessor-capable system.

STAR units are extensible through high-speed low-voltage differential signaling (LVDS) connections that run at up to 1Gb/s. Each board has two sets of five-channel bidirectional LVDS interconnects to link two neighbouring boards. At the same time, each board is wired to Ethernet. High-speed data travels over LVDS, and control data uses Ethernet.

Most processing occurs in the FPGA, coded in VHDL. A growing number of VHDL tools are available for Linux (see sidebar), and we used Quartus from Altera. In our system, we developed algorithms first with GNU-Octave and then ported them to VHDL. Octave and the mostly compatible MATLAB are available for Linux and Microsoft Windows, but Octave has an MPI-enabled version that runs on clusters. We compiled this for a cluster of old DEC Alphas we call zion. MPI-Octave really screams on zion despite the fact that the fastest CPU is only 500MHz.

For our digital board, we used an ARM Linux toolchain from handhelds.org to compile freshly patched 2.4.18 kernel sources. Russell King began ARM Linux when working on a distribution for Acorn computers in the early 1990s. Now, ARM is one of the best-supported processors under Linux and is a real joy to us. Three days was enough to port Linux to our custom hardware, although the Ethernet driver took a couple more days to complete. ARM is easily the world's number one processor by sales, with a huge amount of support for running Linux. This led Tait Electronics to commit to ARM processors in our future processor road map.

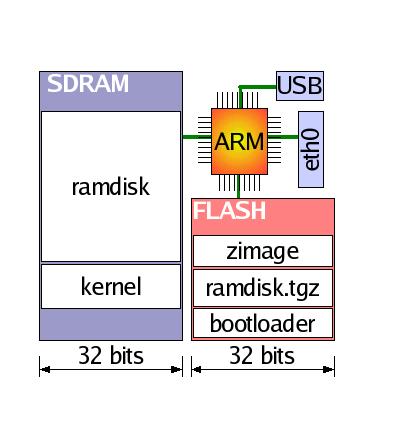

With ARM Linux booting, it was time for a RAM disk. Having 16MB of SDRAM and 2MB of Flash memory on the ARM, we opted for a maximum compressed kernel and RAM disk size of 1,024K each, although the uncompressed RAM disk is 4MB in size. Both are stored in Flash and allow booting without external interaction.

We opted to use BusyBox for common tools, including ls, cd, mount, insmod and ping, and TinyLogin for login and password support. Other onboard utilities handle memory-mapped peripherals and Flash, and netkit-base provides a telnet dæmon that uses TinyLogin functions. Tait Electronics bought a range of MAC addresses from the IEEE to support its Linux-on-ARM development programme, and the MAC address for each board is held in Flash memory.

Figure 2. Each unit has both a Flash-based and a RAM-based filesystem.

We developed many small applications and even got the Abyss Web server running, but these all can't fit into Flash. We therefore NFS-mount a directory from the zion mainframe to each ARM, accessing many gigabytes of extra space. Figure 2 shows the filesystem arrangement.

We also set up SMB mounts to users' shared drives from zion, accessible to the ARM boards over NFS. If a Web server is run on the ARM boards, we end up with a highly interlinked system. Windows users can access part of their own local drivespace through the Web served by way of an embedded ARM board linked over NFS to a remote cluster server.

In late 2001, we obtained the old DEC Alphas (described as boat anchors) and decided to see what we could do with them. First, we modified the built-in bootloader to get Red Hat 7.1 running. We made two major changes. First, we chose one master machine and loaded up its SCSI interface with six hard disks and a DVD-ROM. Five disks became a level-5 RAID array (using raidtools) to store simulation or experimental data, and the remaining disk is for booting and recovery.

The second change was to install the MPI on all machines. Although installation was fairly easy, the need to derive all IP addresses through DHCP caused problems. In the end, we negotiated a fixed IP address for the master machine, now called zion. We run startup scripts on other machines that log their IP addresses onto an SMB mount using RPC (Listing 1).

Once MPI was working, we downloaded the latest Octave source and patched it with Octave-MPI. Since then, Octave-MPI seems to have been taken over by Transient Research (see the on-line Resources section). We set up our MPI system with a script that gathers the IP addresses stored by the script above, pings them and builds an rhosts file. Once dynamic generation of rhosts is complete, we simply run Octave-MPI over 4+1 machines with:

recon -v lamboot mpirun -v -c4 octave-mpi

With the system running, the Octave processing load can be shared across the cluster. We find that Alphas have significantly faster floating-point performance than do Pentiums, but using Ethernet to pass MPI messages slows the cluster down. We haven't benchmarked the system, but a simulation that takes a couple of hours to complete on a 2GHz Compaq PC runs about 10% faster on our first cluster of four Alphas (300MHz–500MHz).

We found GNU-Octave to be an excellent tool for numerical simulations. When executed with the -traditional option, also known as -braindead, it runs most MATLAB scripts. In some cases, Octave provides better features than MATLAB does, although MATLAB has a better plotting capability than the default gnuplot engine Octave uses.

Some engineers prefer to develop on Windows, so we provide a Web interface to MPI-Octave. It uses a JavaScript telnet client served from Apache on zion and some back-end scripting. Scripts were adapted from an on-line MUD game engine. For Windows users, the telnet client script automatically mounts their shared Windows drives on the zion filesystem, runs Octave over telnet and sets up plotting capabilities so that plots are written to a directory on the Web server in PNG format for displaying with a browser. Another option lets users save plots directly to their shared drives.

For debugging, a large debug buffer in the FPGA is accessible to the ARM. We memory-mapped the FPGA with 32-bit high-speed asynchronous access to the ARM, with access in userland or kernel space. Unsurprisingly, in kernel space we use a character driver module accessed as a file. This bursts up to 1,024 data words at high speed and handles all signaling, although the sustained speed is not so good. Userland access is accomplished through the neat method of mmapping to the /dev/mem interface, as long as you remember to create /dev/mem on your embedded filesystem first (Listing 2).

These tools allow us to upload known test vectors, saved from Octave on zion, to the debug buffer. Under ARM control, we route the debug buffer output to the input of a block under test, run the system for a few clock cycles and capture the output back in the debug buffer. Analysing the result in Octave tells us if the block works.

We found visualisation to be an important factor. After our first milestone, we invited some people to see the system. They saw boxes humming away with a couple of green LEDs to indicate everything was working. We noted a distinct lack of enthusiasm at what we believe was a world-first demonstration of the technology, so we realised something more was required. To this end, we chose to display channel models as they adapted in near real time. A channel is the complex path from a transmitter to a receiver, including reflections, multiple paths, dispersion and so on. The system we built sent training symbols over the air to sound the channel before sending data. Sounding gives us a picture of the channel, which we decided to display. We used the FPGA debug buffer on the receiver, with an ARM script running periodically to execute a program to extract the channel data from the buffer, format it and save in an Octave-compatible .mat file on zion. Octave was run non-interactively on zion to read the channel data periodically, analyse it and generate four plots as PNG image files, which a zion Web server PHP page displayed as a visualisation updated every four seconds (Figure 4).

Our Linux-powered digital boards normally run complex processing algorithms and communicate over air and Ethernet to other systems. Even under laboratory conditions, it is difficult to know whether all components are operating correctly, so we decided to utilise the power of Linux to implement self-test and monitoring solutions. Like our visualisations, this ties many components together in a flexible way.

Nontechnical users demanded a graphical interface, which we could have created using GTK, Tk, Qt or something similar, but we decided instead on PHP-powered Web scripting. This allows users of all platforms to access the system. The C-like language syntax makes it easy and quick to use for C programmers, and the familiarity of modern users with Web interfaces helps. The source code for most applications is less than 50KB in size, which is a major advantage in debugging and testing and consequently improves our confidence in that code.

Unfortunately, such a user interface has a couple of disadvantages: first, when a background event must be brought to the attention of a user and, second, when the system must interact directly with hardware. The first problem can be solved through the use of ticker-type messages in a separate frame. In our system, we solved the second problem through the use of small low-level C programs with a file-based interface to PHP.

In truth, our system is quite convoluted. The controller in each unit is the ARM processor, but the controller for all controllers in a multi-unit system is the Web server serving the PHP scripts. For self-tests, the system implements a repetitive monitor script running on each ARM every five seconds and interrogates the system for the Web server. Details are written to a file named after the IP address of the Ethernet on each ARM. The monitor script also is responsible for ensuring that each operational system is synchronised in time to zion. We didn't use NTP due to code size and because we require sufficient time resolution only to prevent shared filesystem time consistency errors. We script zion to write the current time and date, using the date command, to the file every five seconds, and each ARM reads that file every five seconds to set its time. This gets around time synchronisation problems and fixes timestamps on files. We also use it as a watchdog to reset boards more than a minute out of date.

Apart from self-tests, the script also queries version numbers of RAM disk and kernel on startup and writes this to a status file. A final use of the script is to execute board-specific instructions. These are written by the PHP control Web page to tell each ARM board what it should be doing. Instructions from PHP are written as a shell script to be executed by a single board, identified by IP address.

All units run identical kernels and RAM disks stored locally in Flash memory and verified against master copies on zion at startup. Any inconsistency causes the correct kernel or RAM disk to be burnt into the local Flash memory. We built custom Flash memory tools to do this. In practice, we have had no storage errors, but we use this to roll out new versions of kernel and RAM disk without user intervention.

The PHP Web pages refresh every five seconds using the autoload HTML tag. Of course, this works only if at least one user has a browser currently viewing the page. If not, the information probably isn't required anyway. A manager's-eye-view Web page hides almost all useful information but looks great. Real users can click down through the levels to get to individual scripts that customise each board.

Linux software on the ARM sets up FPGA firmware to stream small packets of data from the wireless system to a debug buffer in the FPGA. In slower time, the ARM extracts this and stores it on zion. These files can be analysed automatically to look for faults (like all 0s) and if found, the user is alerted through the Web pages.

We recently have started to think about products rather than pure research. It is likely that we will communicate IP packets and some form of embedded Linux will power the product. This will happen not only because we relied upon it during development, but there are few viable options for handling IP packets. WinCE is slow and bloated, and VxWorks is lean but costly and lacks in protocol support.

Tait Electronics is a nonprofit electronics trust run to benefit the employees and society of Christchurch, New Zealand. It was founded by Sir Angus Tait more than 30 years ago. It exports 97% of its mobile radio products to more than 200 countries worldwide.

Resources for this article: /article/7648.