When an upgrade works, you get a few more features or better performance. When an upgrade fails, you're in for a weekend of pain. Now, here's how to back off to the old version and keep the system up.

How many times have you installed a great new piece of software only to find you really didn't want to install it after all? To make matters worse, when you installed this software, you had to upgrade several other software packages and install additional ones from scratch. To put things back the way they were, you had to locate earlier versions of the upgraded packages from a multitude of sources, downgrade to these versions and remove any newly installed packages. Of course, if you did not keep a good record of what packages actually were changed and what their previous versions were, things got even worse. Wouldn't it be great if you instead could push one button or run a single command and roll back this upgrade?

In some environments the ability to roll back an upgrade quickly is not only desirable, it is a requirement. For instance, when upgrading a telecommunications company's equipment, software and hardware vendors are required to upgrade equipment in a limited time frame, known as a maintenance window. In this same maintenance window, they also must be able to back out any changes made by the upgrade. Failure to back out an upgrade within the maintenance window results in strict financial penalties.

As desirable as an automated rollback of RPMs is, RPM has not supported this option until recently. To be fair, RPM has supported downgrading a set of packages. For instance, if you upgraded some RPM foo-1-1 to the version foo-1-2, you could use the --oldpackage switch with the rpm command to downgrade to a previous version; like this:

# rpm -Uvh --oldpackage foo-1-1.i386.rpm Preparing... ################# [100%] Upgrading... 1:foo ################# [100%]

If the upgrade to foo-1-2 did not require you to upgrade or install any additional RPMs, the --oldpackage switch worked fine. All you had to do was find the original foo-1-1 RPM, and you were home free. If, on the other hand, you did need to install or upgrade other RPMs on which foo-1-2 depended, you then had to search for those RPMs in various locations—on your install media, on your distribution's errata site, in various RPM repositories or on various project Web sites.

Once you had hunted down all the dependent RPMs, you would need to downgrade all the ones you had upgraded and erase the fresh ones you had installed. If, instead, you reversed this order and erased the fresh RPMs you had installed before you downgraded the RPMs that had been upgraded, you were greeted with errors from RPM complaining that these packages were required by foo-1-2. In short, the old way of rolling back a set of RPMs was painful and fraught with error.

Early in 2002, Jeff Johnson, the current maintainer of RPM, began to remedy this rollback problem when he included the transactional rollback feature into the 4.0.3 release of RPM. This feature brought with it the promise of an automated downgrade of a set of RPMs. Like many new features, it was rough around the edges and completely undocumented, except for a few e-mails on the RPM mailing list (rpm-list@redhat.com). Over the past year and a half, transactional rollbacks have matured steadily. In the current RPM 4.2 release, which comes with Red Hat 9, transactional rollbacks are quite usable.

Under the hood, RPM treats any set of RPMs it installs as a discrete transaction. This is true when installing one RPM by itself (a transaction of one RPM) or several RPMs simultaneously. Each of these transactions is given a unique transaction ID (TID). As each RPM is installed or upgraded, its entry in the RPM database is marked with the TID of the transaction within which it was installed. This allows RPM to track within which transaction each RPM was installed or upgraded.

To roll back an RPM transaction set, RPM must have access to the set of RPMs that were on the system at the time the transaction occurred. It solves this problem by repackaging each RPM before it is erased and storing these repackaged packages in the repackage directory (by default, /var/spool/repackage). Repackaged packages contain all the files owned by the RPM as they existed on the system at the time of erasure, the header of the old RPM and all the scriptlets that came with the old RPM.

You may be wondering how this design helps with upgrades. After all, if you upgrade an RPM you're not erasing it. You are erasing it, though, because upgrading an RPM has two parts: the new package is installed, and the old package is erased. This means every time you upgrade a set of packages, RPM first repackages all packages being updated, then installs all the new packages and, finally, erases all the old packages. When RPM repackages the old packages, it also marks the repackaged packages with the TID of the running transaction. The end result is you don't have to scour the Net, media or backups for the RPMs you updated. Because the repackaged packages contain the files that were currently on your system at the time of the upgrade, the need to restore configuration files from backup is eliminated. As a side effect, the md5 checksums of the files in a repackaged package are likely to be wrong, because RPM does not recalculate each checksum when creating the repackaged package. This is not a problem for RPM when it rolls back transactions, but you need to use the --nodigest option to manipulate repackaged packages directly.

Once the repackage directory is populated, RPM requires only a rollback target (the date to which it is rolling back) to perform the rollback. RPM then determines by TID which transactions have been applied to your system since the rollback target date. Next RPM takes this set of transactions, sorts them in the order of most recent to least recent and does the following for each one:

Finds all the repackaged packages that are marked with this TID.

Finds all the currently installed packages that are marked with this TID but do not have corresponding repackaged packages.

Builds a rollback transaction. Repackaged packages are added to this transaction as install elements, and installed packages that have no corresponding repackaged package are added as erase elements.

Runs the newly built rollback transaction.

By repeating these actions for each transaction from the most recent one to the one nearest or equal to the target date, RPM walks through all transactions that have occurred since the rollback goal and undoes them.

You may be thinking this process is complicated, but using transactional rollbacks actually is rather easy. As a simple example, let's install a single RPM and roll it back. The most crucial point you have to remember is that whenever you do an upgrade or simple erase, you must tell RPM to repackage the old package before it is erased. To do this, use the --repackage option:

# rpm -Uvh --repackage foo-1-2.noarch.rpm Preparing... ############################# [100%] Repackaging... 1:foo ############################# [100%] Upgrading... 1:foo ############################# [100%]

Using this option, RPM first repackaged the old package and then upgraded the new one. On an erase, you also need to use the --repackage option, like this:

# rpm -e --repackage foo

RPM does not show any output from an erase, but if you look in the repackage directory after an erase, a repackaged package is there.

To roll back this RPM transaction, use the --rollback option followed by the rollback target. The rollback target can be an actual date or something like one hour ago (the date specifier allows the same date formats as the cvs(1) command's -D option). So, if an hour after upgrading foo, you decide you don't want it, you could type:

# rpm -Uvh --rollback '2 hours ago' Rollback packages (+1/-1) to Thu Jul 31 23:26:52 2003 (0x3f29ddfc): Preparing... ########################### 100%] 1:foo ########################### [ 33%]

The output Rollback packages (+1/-1) shows that RPM is going to add one package, the previous version, and erase one package, the currently installed version.

Transactional rollbacks are only as good as your local repackaged packages repository. One quick way of making them fail is to upgrade or erase something without using the --repackage option. From my experience, it is pretty easy to forget to use this option. Therefore, if you are going to use transactional rollbacks, you want to configure RPM to repackage all erasures automatically. Do this by setting the %_repackage_all_erasures macro to 1 in your /etc/rpm/macros file. If the file does not exist simply create it:

%_repackage_all_erasures 1

By default, RPM does not roll back a newly installed package; that is, it does not erase packages that were not on the system at the time of your upgrade. You probably don't want this to be the default behavior, so you need to tell RPM to allow for this. To do this, set the macro %_unsafe_rollbacks to the date beyond which you do not want to allow an RPM to be completely erased on a rollback. A good value for this is some time after your system's initial install. This date should be in seconds since epoch. To convert a date to seconds since epoch, use the date command:

date --date="8/1/2003" +%s 1059710400

If you wanted to tell RPM not to remove packages completely that were installed on or before 8/1/2003 (the date in the above example), you would add the following to the /etc/rpm/macros file:

%_unsafe_rollbacks 1059710400

The only other thing you may want to configure is where RPM puts the repackaged packages. One reason for doing this is to ensure they are placed in a partition that has ample space. To change the repackage directory, set the %_repackage_dir macro to the directory where you wish to store the repackaged packages:

%_repackage_dir /my_rp_repository

Now you have a system that automatically repackages all erasures (so you or someone else does not forget), erases newly installed packages on a rollback (but won't erase your whole system) and places the repackaged packages where you want to store them.

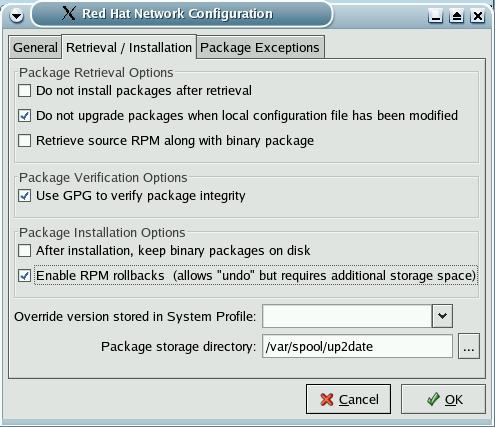

In Red Hat 9, up2date supports rollbacks using RPM's transactional rollback mechanism. Configuring it to support transactional rollbacks is as simple as running up2date-config, clicking the Retrieval/Installation tab and then clicking the Enable RPM rollbacks check box (see Figure 1). You have to configure RPM itself as described in the previous section. When you upgrade your system using up2date, once you have configured both RPM and up2date, RPM creates the repackaged packages of RPMs you are updating before it upgrades those packages.

Figure 1. Enabling RPM Rollbacks in up2date

To list the different known rollback targets, type:

up2date --list-rollbacks

You should receive a listing like this:

# up2date --list-rollbacks install time: Sun Jul 27 20:49:55 2003 tid:1059353395 [-] goo-1.0-1.0: install time: Tue Jul 29 20:44:25 2003 tid:1059525865 [-] foo-1-2:

This command is handy even if you are not actually using up2date, because the rpm command does not provide a way of displaying such information.

To undo a transaction, use the --undo option, which undoes the last transaction that was installed. Simply type:

# up2date --undo

If you want to roll back multiple transactions, run this command multiple times. The ability to roll back from the GUI is not supported.

RPM normally delivers packages using a best effort strategy, meaning if one or more RPMs fails to install, the remaining RPMs in the transaction still are installed. This is a desirable behavior in some environments, but in others it would be much better if, instead, RPM automatically rolled back the failed transaction. Because I work in such an environment (telecommunications), I wrote a patch called the auto-rollback patch. This patch allows you to configure RPM such that if a transaction fails, RPM automatically rolls back the failed transaction. It does leave behind the failed RPM if it failed in its %post scriptlet; hopefully that soon will be fixed (patches anyone?).

If you would like to use this feature, you can download the patch (or RPMs that have the patch applied) from lee.k12.nc.us/~joden/misc/patches/rpm. Once you have a version of RPM installed with the auto-rollback patch, you need to configure RPM to use the auto-rollback feature. To do so, edit /etc/rpm/macros and add the following macro definition:

%_rollback_transaction_on_failure 1

After doing this, the next time you install/upgrade a set of RPMs and one fails to install, RPM automatically rolls back the failed transaction, except for the failing one if it failed in the %post scriptlet.

RPM transactional rollbacks provide an efficient way of undoing RPM upgrades. They also provide a solid building block upon which system update programs (such as up2date, yum and apt-get) can provide automated rollback functionality. However, transactional rollbacks are not for everyone. To quote Jeff Johnson, “the --rollback option...requires absolutely perfect system administration and is mostly mechanism, not policy.” Transactional rollbacks are an all-or-nothing affair. Care must be taken to ensure that all erasures are repackaged, as RPM's ability to roll back transactions is only as good as its source of repackaged packages. The administrator must ensure that extra space is allocated for the storage of the repackaged packages. Finally, RPM's transactional rollback feature is a work-in-progress. That said, RPM transactional rollbacks have come a long way from their beginnings. If you want to ensure that RPM updates to a system can be undone quickly, they may be exactly what the doctor ordered.