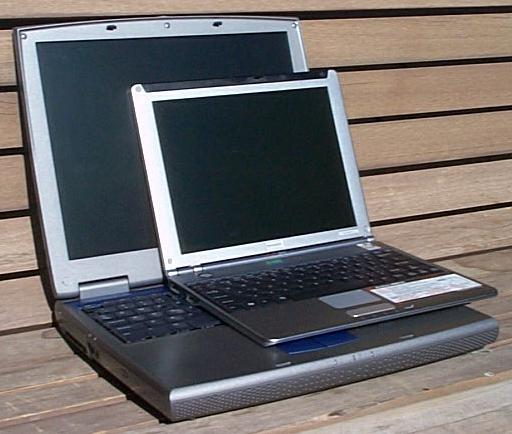

Built around the Sharp Actius MM10, the Meteor is the smallest fully functional notebook I've yet seen.

We live in the midst of an industry rife with buzzwords. In many ways, these quick phrases are the coin of the marketing realm; they are words that press some personal hot button, driving us inexorably toward the purchase of the latest and greatest technological device. They're powerful tools, but the use of these buzzwords often serves only to blur the line between new device types.

Take, for example, the current hot word used to describe mobile computers, notebooks. Every major manufacturer has a notebook in its product line. The word itself, it seems, is evolutionary, derived from the concept of a laptop computer. Notebook says to the consumer, “I'm smaller than an unwieldy old laptop, small enough to take you back to your college days and those indispensable collections of paper bound together with thin spiral wire.”

As is so often the case, the success of the word notebook has led to its widespread misuse. You'd be hard pressed to find a major manufacturer carrying a line of laptops these days. The notebook imagery is too powerful, leaving manufacturers with little choice but to throw the old laptop description in the dustbin. Even if the device weighs in at better than five pounds, it sells better as a notebook than it ever will again as a laptop.

Fortunately, some real notebooks are on the market that serve to clear the confusion. These are devices that provide congruence between the notebook imagery and its reality. Lying somewhere between a PDA and a laptop, notebooks fulfill a critical niche for users weary of lugging the old laptop through airports and hotel lobbies. One device in particular, the EmperorLinux Meteor Notebook, has re-established the descriptive value of the notebook buzzword. With dimensions and weight that rival some of my own college notebooks, the Meteor is Linux-ready and built to travel for any savvy computer user.

Built around the Sharp Actius MM10, the Meteor is the smallest fully functional notebook I've yet seen. Weighing in at a mere 2.1lbs (with battery), it's light enough for even the most wrist-weary mobile worker. With a thickness of .52", the real danger is it may become lost in the soft-sided leather briefcase I've used for years to carry my laptops. The moment I pulled the Meteor from its box, I knew it held real promise to reclaim the notebook buzzword for what it really should be.

In its factory configuration, the Meteor is marketed and installed by Sharp as a Microsoft Windows machine. Filling a valuable niche in the mobile market, EmperorLinux converts these notebooks and replaces the original OS with Red Hat 9. The match of the two components is nearly perfect, providing an extremely usable Linux desktop and application set. The 2.4.2x Linux kernel is custom configured in the EmperorLinux shop to provide such mobile-valuable features as software hibernation. EmperorLinux does provide the Meteor with a minimal DOS installation for legacy users, allowing GRUB to handle the bootloading tasks.

Clearly, some trade-offs are made in the Meteor for the sake of size. I anticipated that its screen and keyboard size might make it difficult to use. Even my current laptop, a Dell Inspiron 1100, has a 14" screen and a keyboard that approximates the size and feel of a desktop computer. Surely, I thought, that look and feel couldn't be replicated on a device so small. But upon investigation, the 10.1" XGA LCD screen is bright and sharp, offering far better contrast than my Dell or many of the other laptops I've seen and used. Running at a resolution of 1024×768, the display is surprisingly easy on the eyes, suitable even for graphics manipulation in The GIMP. With the anti-aliasing support in Red Hat 9, I quickly came to prefer the Meteor over the Dell. The display and feel vs. size compromise turns out to be hardly a compromise at all.

The keyboard, although undeniably tight, retains much of the feel of a laptop. In other words, with regular use, it's quite easy to make the adjustment from desktop to notebook. I made it without a hitch, even with the dexterity of a corn-fed Iowan, manual dexterity that's often compared to that of our primary export—hogs. The lone exception was the location of the touchpad. It took some mental training to avoid tapping the pad with my thumb and unexpectedly launching an application.

On the hardware side, a little more ground is given for the sake of the Meteor's compact size. Although these may present some small aggravations to hard-core coders, my sense is they are not the target market for the Meteor. With a 1GHz Transmeta Crusoe processor, the Meteor does feel perceptibly slower than my regular laptop when compiling and installing applications. The latest release of OpenOffice.org took nearly twice as long to install on the Meteor as it did on the 2GHz Celeron-equipped Dell laptop. However, the Crusoe architecture left little discernible difference in execution speed for most applications. Once compiled and installed, OpenOffice.org seemed to run as easily and as quickly on the Meteor as it did on any other platform in my home. My other killer mobile application, Mozilla, opened and churned through pages and images with the ease of a much more powerful desktop.

With 256MB of fixed DDR RAM and a 15GB hard drive, the Meteor once again has hit the sweet spot for most users. That there's not more RAM or storage space is, ultimately, a fair trade for making this device as small and mobile as it is. I missed neither when trading my daily use of the Dell laptop for the Meteor.

If you're of the personality type that is inextricably trapped in those marketing buzzwords I mentioned, let me give you a new one to distinguish the Meteor from the current crop of notebooks, ultra-mobile. For starters, the Meteor comes equipped with built-in Wi-Fi. With the installed Red Hat networking tools, it's a simple task to set up a Wi-Fi DHCP connection and start surfing or checking e-mail within a matter of minutes. No hot spot close by? No problem. The Meteor also features a built-in 10/100 Ethernet port or, at worst, a PCMCIA slot into which you can slide a modem card. When you put that diversity of connections in its proper perspective—that is, a device a half-inch thick—the Meteor easily deserves the ultra-mobile label.

The custom kernel configuration EmperorLinux provides unlocks some other great hardware features in the Meteor. The notebook provides FireWire and USB capabilities, with one and two ports respectively. The Meteor also features a unique USB-connected vertical docking cradle. This feature allows a user to share the notebook's hard drive with a desktop system or to sync data between the desktop and notebook with ease, even when the notebook is powered down. With the Meteor off, I placed it in the cradle. This assigned the drive to /dev/sdb. I then was able to mount the drive at /mnt/meteor and the /home partition at /mnt/meteor/home. With this completed, I moved data between the machines effortlessly from the command line. I also completed these tasks by opening multiple instances of Nautilus, in effect dragging and dropping data from one machine to the other.

Figure 2. The Meteor Syncing from Its Cradle to a Desktop

In short, the real strengths of the EmperorLinux Meteor are many. It's highly mobile, with the capability to connect to the network across the full range of options. With Wi-Fi becoming increasingly pervasive, the Meteor/Red Hat combination provides both built-in hardware and easy configuration for connecting to the nearest hot spot. The custom kernel relieves even a newbie user from the pain of unlocking all the built-in hardware features. And the sync/storage capabilities provided by the USB docking station are the quickest path to taking your data on the road.

If those features don't fill your bill, consider the documentation provided by EmperorLinux. Though a thin book, it provides step-by-step guidance for setting up and using the most critical features of the Meteor. Unlike some manufacturer-provided documents, the Meteor documentation is kept current with the version of Linux in use in the Meteor. It also features custom kernel-specific information for those who are technically inclined. The documentation is exactly enough, without being too much.

You might think I found the Meteor to be without flaws, but that's not quite true. The flaws, however, are not show-stoppers. As expected, they're related in large part to the size of the Meteor. There is no built-in CD-ROM, although you can connect one to a USB port. As I've already noted, the touchpad placement is a bit awkward. I've never been a big believer in the mouse nubbin found on some laptops, but the size of the Meteor would make it a good candidate for such a pointing device. The processor is a bit too slow to push the Meteor into the class of machine necessary for developers and coders. Despite its power-miser Transmeta Crusoe processor, the Meteor sucks down a battery like a script kiddie sucks down a Big Gulp. On average, I could expect less than two hours of battery life before breaking out the power cord. The built-in Wi-Fi always is on, regardless of whether it has a connection, which adds to the power requirements and diminishes battery life. Finally, at $1,700 US, you actually might find the small Meteor a bit bigger than your wallet. Even at that price, it's a good investment of time and money for the enterprise.

Figure 3. Its small size makes the Meteor a true notebook.

So, let's refine our marketing-speak a bit. Laptop does not equal notebook. The Meteor Notebook is proof of that, it being the only Linux-equipped device truly to fill the notebook bill. Call it an ultra-mobile if you must, but the Meteor surely will redefine how you hear the notebook marketing message from now on.