It's a record label, but it's not evil. How to build a business without ripping off artists and annoying customers, and why you might need three different kinds of Web server software.

Magnatune is an Internet music record label. It was born out of personal experiences from my wife releasing her CD on a British record label and some observations I'd gathered about the music industry. Magnatune is different from traditional labels in the following ways:

We split the sale price of all purchases 50/50 with our artists.

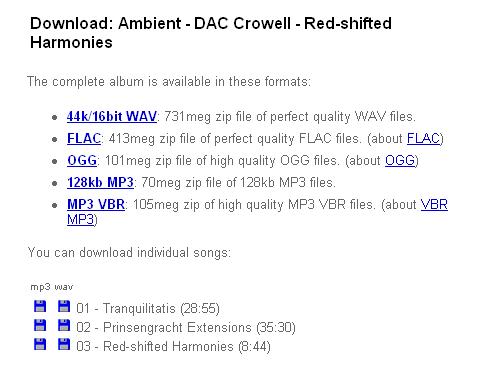

We sell only downloads and never use digital rights management (DRM). Purchasers may download albums as perfect-quality WAV or FLAC files, as high-quality variable bit-rate Ogg Vorbis files or MP3s or as 128k MP3s. Buyers can choose how much they want to pay, from $5 to $18 US.

You can listen to all our music as streaming 128k MP3s (entire albums, not samples) as well as on Shoutcast MP3 stations. Two clicks on Magnatune queues a never-ending selection of our music in the genre of your choice. Our assumption is you eventually will hear something you like and want to buy it.

All our free music is licensed using the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. This allows noncommercial use of the music at no cost, as well as derivative works, as long as the same Creative Commons license applies. If someone uses our music for commercial purposes, they have to license it for a modest fee. All our licensing is done on-line with a standard rate calculator, and we don't discriminate based on the kind of use. For example, we can't and won't block your use of our music if we don't agree with your views or your musical style.

We're successful and profitable. Our top artists are making about $6,000 US a year in royalties, while the average musician makes about $1,500 US per year. We work directly with musicians or musician-owned labels, never with labels who funnel the money to themselves.

Magnatune was born out of personal experiences from my wife releasing her CD on a British record label and some observations I'd gathered about the music industry.

When my wife was signed to a British record label, we were really excited. In the end, she sold 1,000 CDs, lost all rights to her music for ten years (even though the CD has been out of print for many years) and earned a total of $45 in royalties.

The record label that signed her wasn't evil. They were one of the good guys, and gave her a 70/30 split of the profits, of which there were none. The label got battered at every turn: distributors refused to carry the label's CDs unless it spent thousands on useless print ads, record stores demanded graft in order to stock the albums and, in general, all forces colluded to destroy this small, progressive label.

Radio is boring. Everyone I know listens to interesting music, yet good music rarely is played on the air. Most musical genres barely are visible in record stores, and they are totally absent from the airwaves. These days, radio plays mostly Country, Pop and Rock, with a little bit of dull, safe Classical thrown in.

CDs cost too much, and artists receive only 20 cents to a dollar for each CD sold, if they're lucky. And, most CDs quickly go out of print. I buy more CDs from eBay than from Amazon.

On-line sales, such as Amazon.com, often cost artists 50% of their already pathetic royalty, due to a common record contract provision. International sales and markdowns often net the artist no royalties.

Record labels lock their artists in to legal agreements that hold them for a decade or more. If the agreement is not working out, labels don't print the band's recordings but nonetheless keep artists locked in to the contract, forcing them to produce new albums each year. Even hugely successful artists often end up owing their record labels money because the advances they're initially paid are structured as a loan to the artist. Furthermore, the label does its accounting in such a way that profits rarely are shown on the record company's books, hence no money exists to pay down the advance.

Using the Internet to listen to music usually is tedious. There are too many ads, too many clicks and the sound quality is not great. Simply put, it's too much work for not enough reward. A well-run Internet radio station, such as Shoutcast or Spinner, solves that, but the entrenched record industry wants to kill them too, through onerous licensing terms and annoying DRM schemes.

Given all these factors, I thought, “why not build a record label that has a clue?” Create a label that helps artists get exposure, make at least as much money as they would make at traditional labels and get fans and concerts. Magnatune is my project. The goal is to find a way to run a record label in the Internet reality: file trading, Internet Radio, musicians' rights, the whole nine yards. These aren't things that can be ignored.

Figure 1. The Magnatune home page (magnatune.com) answers visitors' top eight questions.

I believe that the home page of any successful company, project or organization needs to address eight issues immediately. As shown in Figure 1, Magnatune's home pages answers all eight:

Where am I? — a graphic logo on the top left or top right does the trick. It's even better if you have a catchy line. For Magnatune, it's “We are not evil”.

Why should I care? — a one-line description of what you do and, if possible, why someone should be interested. For Magnatune, it's “Internet music without the guilt” followed by “Magnatune, the Open Music Record Label”.

What do you want me to do? — for first-time visitors, it should be clear what the next step is. For Magnatune, I want people to listen to the music immediately, so it says “Explore a music genre: Classical, Electronica, Metal & Punk, New Age, Rock, World, Others”.

Why is this cool? — there are way too many sites on the Internet, and people have a limited amount of time. You've got the visitor's attention for a few seconds, so you need to explain quickly why this is something he or she wants to support. If you're doing e-commerce, expect that your visitors are jaded. If you answered the second question well, you've got another 30 seconds of their attention. Magnatune starts with: “We're a record label. But we're not evil. We call it 'try before you buy.' It's the shareware model applied to music.” The concepts of record label, not evil and shareware are an odd combination, so now they're interested.

What's new? — give people an incentive to come back to your site by making it easy to see what's changed. There's a lot of new stuff at Magnatune (new press coverage, for example), but most people care only about our new artists and albums, so that's what's on the home page.

Newsletter signup — every Web site should have a newsletter. If you put the signup on the home page, you can expect 2% to 5% of Web site visitors to sign up.

I want to know more — an “about” section also is crucial. The founders should explain why they created the site, project or company.

I want to steer — despite all these hints on what to do next, visitors often want to decide for themselves where to go. On Magnatune, 15% of people coming to the home page click on the Artists tab. Make the major site navigation options clear.

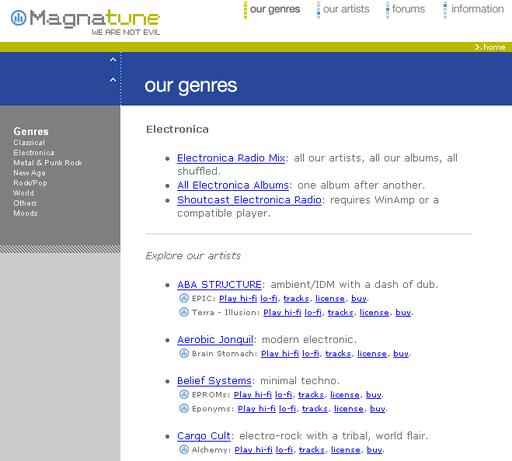

Figure 2. “Play” links on the Electronica page (magnatune.com/genres/electronica) offer immediate gratification.

My main gripe with most music sites is they take too much of my time, when what I want to do is play music and get back to my work. My second gripe is they usually don't give you enough music and not at a high enough quality to make a decision. Most of the people I know buy music by hearing it first, either on the radio, at a concert, at a friend's house, at a restaurant and so on. Because only a small number of visitors to a music site already know the bands, isn't it reasonable to let visitors listen and make up their minds? At Magnatune, you can listen all you want, with minimal effort, to high-quality 128k MP3s.

Once a user clicks on the Magnatune home page to select a genre, such as Electronica (see Figure 2), a Web page is displayed that shows four main choices: 1) listen to every album in Electronica, one album after another, 2) listen to a mix of our Electronica artists, 3) listen to the entire album of any of our Electronica artists and 4) click on an artist to learn more. The first three choices offer users immediate gratification by allowing them to hear music immediately.

People would prefer to find music from their friends or on their own than be force-fed by the major music outlets—radio and MTV. In the 1980s, most software couldn't be evaluated before it was purchased, yet today no one buys any software without first trying it out. Eventually, all music will be shareware: the competitive advantage simply is too great.

Magnatune runs on open-source software. Five 2.4GHz 1U rackmount boxes run Linux. Disk storage is provided by hardware RAID on four rackmount drive arrays, each with seven drives for a total of 28 drives. Each array is configured for RAID5 with one hot spare.

Apache 2 running PHP and OpenSSL serves all the HTML pages. When Magnatune was Slashdotted, I found that Apache could not keep up with the load for images. All HTTP image requests now are off-loaded to AOLserver, which had the lowest latency to serve images at high loads.

Mathopd, a single-threaded asynchronous HTTP server, is used to serve all MP3 files, as it is extremely scalable with large files. We customized Mathopd to return the same Expires: HTTP response header on images that Yahoo uses. Mathopd has more latency than AOLserver, which is why we don't use it for serving small images.

All Web pages in Magnatune run PHP. Purchases are logged to a MySQL database. A Perl script creates the track listings and m3u playlists. Tcl scripts handle all other tasks, such as making ZIP, Ogg Vorbis and FLAC files and making per-album password configuration files for Apache. Apache HTTP passwords are used to protect all purchasable downloads. We use rsync to distribute files among the servers.

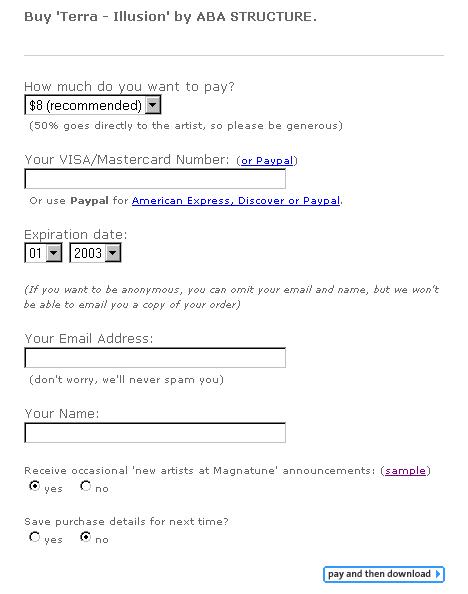

Several unusual features can be found in Magnatune's music-download purchasing process. Buyers determine how much they want to pay, we don't use a shopping cart, we support PayPal and anonymous Visa purchases are allowed.

Clicking the Buy button brings up a page with the question “How much do you want to pay?” and offers choices from $5 to $18, with $8 as the recommended price (see Figure 3). A disclaimer states, “50% goes directly to the artist, so please be generous”. The average purchase price in September 2003 was $9.82, which shows that when given a choice, buyers prefer to pay more than we ask.

Figure 3. Because 50% goes to the artists, buyers choose to pay more than the minimum price.

I decided not to use a shopping cart at Magnatune because of the widely discussed problem of shopping-cart abandonment. When people are excited about an album and click the Buy button, that's the time to capture the sale. With a shopping cart in place, a user often goes looking for more things to add and that initial buying compulsion is gone if they don't find something.

On any given day, we find that 30%–50% of purchasers pay with PayPal. I believe many people prefer PayPal because with a credit card the merchant still has your credit-card number after the transaction completes. Your personal data is out of your control. With PayPal, the transaction ends with your payment, and no future risk is possible.

PayPal offers two ways for merchants to be notified of payments. IPN is a system where PayPal issues an HTTP callback to your Web server with a specific ID. Your Web server software then takes the ID and calls PayPal over HTTP to fetch transaction details. This is a highly secure option, but it has two problems: it is significant work to code, and it doesn't allow an immediate download after purchase, because your Web server needs to wait for the notification. Many shopping-cart programs support IPN and deliver download instructions by e-mail. We do not use an IPN/e-mail-based system, because we found that ISP-based antispam programs blocked many of our download-instruction e-mails, which led to very unhappy buyers who were not aware of the blocked e-mail.

We use the second, simpler PayPal system, in which PayPal sends the user back to our site with HTTP POST data after a transaction occurs. This is simpler to program and fairly reliable. Not all PayPal payments are instantaneous, however. The payment does not arrive in the vendor's account for several days and may not come at all, so the merchant has to decide whether to allow the immediate download. We decided to trust our users and give them the download immediately.

Our credit-card processor would like us to ask for a name, phone number and postal address (as well as three-digit AVS) on credit-card transactions, but we're under no obligation to do so. Our credit-card company charges us a 1% fee for not having this data at checkout, but on a $10 purchase this is only 10 cents. This fee pales in comparison to the 25-cent Visa fee and the 25-cent Internet-gateway fee, so we feel it's well worth it.

On the Magnatune Buy page, we require only a customer's credit-card number and expiration date—that's all we need to complete the transaction. We do ask for a name and e-mail address, stating: “If you want to be anonymous, you can omit your e-mail and name, but we won't be able to e-mail you a copy of your order.” Asking for a minimal amount of data at purchase time makes it quick for people to fill out the purchase form. Additionally, not requiring an e-mail address means the buyer doesn't need to worry about e-commerce spam resulting from the purchase.

Immediately after making your purchase, you are sent to a Thank You page that contains a URL for downloading the music. A simple four-character HTTP name and password is given. The instructions also are e-mailed if an e-mail address was provided with the purchase. The download page provides the album in a variety of formats (see Figure 4). You can download a perfect-quality WAV or FLAC file and have an exact replica of the original CD. Ogg Vorbis, MP3-128 and MP3-VBR files also are provided. You can download any and all variations you like for as long as you like (passwords don't expire). The entire album is available as a single ZIP file, for ease of downloading. The ZIP file provides a modest amount of compression, about 10% on WAVs. More importantly, it means you can click Download on one file, let it run for an hour (on a DSL or cable line) and have the entire album without any more fuss.

Figure 4. It's download time. Pick a format, any format.

Clicking the License button next to any album brings up a page (see Figure 5) with the question “what kind of music license?” Sixteen different scenarios are displayed, such as Movie Use, Radio Advertising, Web Site, CD Compilations and even On-Hold Music for telephone systems. The connected page outlines the relevant variables for that scenario, and a price quote is given. The user enters the project details and then is sent to a Check Out page with a music license agreement, which is valid as soon as the fee is paid.

Since its launch in May 2003, Magnatune has been discussed on everything from Slashdot, Fark and BoingBoing to Wired and NPR. During these press events, we've experienced huge bursts of Web traffic. I run five servers at two different locations, each with 100Mb feeds, and send load-balanced pages with dynamic PHP URLs to each of them. I've found this to be sufficient for the current demands. However, as Magnatune has been growing by 30% in traffic and revenue each month, I'm seriously looking at peer-to-peer as a load balancing and scalability solution.

As I'm writing this article, Magnatune has about 60 musicians and 130 albums and is growing by about 15 musicians and 30 albums per month. My top musicians should see about $6,000 US of royalties in a year. On average, musicians should see about $1,500 US each year. If the 30% growth holds up, I'll be able to pay my musicians even more. More than anything, that's what excites me: that I'm able to have a material impact on these musicians. They are excited by the success, people are hearing their music, and the artists have the financial wherewithal to continue recording great albums.