Look up the right word, learn how to pronounce it and translate what you want to say into Hungarian.

It is all about understanding each other, François. Whenever we open up a dialogue with someone from another country, we are making an attempt to establish a common ground for communication, usually choosing one language both can understand or, if that fails, translating back and forth.

Quoi? Of course, you are right, mon ami. Sometimes it is difficult to make yourself understood even by those who share your language. Thinking you know what a word means is no guarantee the person you are talking to interprets that word in the same way. That is one of the reasons we have dictionaries—that and Scrabble.

Ah, mes amis! It is good to see you all. Welcome to Chez Marcel, home of fine Linux fare and great wines from the world over. Please sit and be comfortable. François and I were discussing the challenges of being understood and of properly getting your meaning across. François, as you already know all this, quickly go down to the wine cellar and bring back the 1999 Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon we were tasting earlier—or rather submitting to quality control.

Words are important and the right words even more so, as every writer can tell you. This especially is true when you are trying to communicate with someone who doesn't share your language. Using your Linux system, you can take some joy in knowing that you are helping to improve understanding between yourself and others.

The meaning of words, true or otherwise, may be no more than a click away. If you are running KDE 3.0 or higher, try this trick. Let's say you want to find the definition of “cooking”. Open up Konqueror, then type dict: cooking in the Location field. Press Enter, and Konqueror does a search for you in the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. To do a thesaurus lookup, type ths: cooking instead.

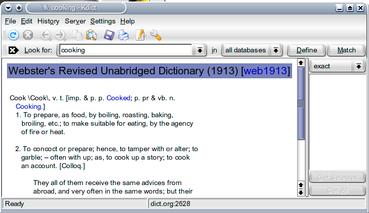

KDE has a nice, integrated dictionary application called Kdict, part of the kdenetwork package. You'll most likely find Kdict in your Utilities menu under the KDE application launcher (the big K). You also can launch it from the shell with the program name kdict (Figure 1). Enter and Kdict connects to various on-line dictionaries to pull up the appropriate definition. Those resources include the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Wordnet, The Jargon File, The Devil's Dictionary and others.

Figure 1. Kdict provides for easy on-line dictionary lookups.

For rapid-fire access to Kdict, you can pop a handy little applet into your Kicker panel. Here's how: right-click on the big K, select Panel menu®Add®Applet®Dictionary. Now, you should see a new program applet labeled Dictionary with three small buttons to the top right on your Kicker panel. On first start, only the C button is visible (define selected text), and the other two are grayed out.

Figure 2. Rapid-Fire Access to Kdict

Enter text into the small window, either a word or a phrase, press Enter, and Kdict appears with that definition as collected from the various sources. You also can select (double-click) a word on a web page or document you are viewing and click that C button in the applet. Kdict automatically launches and provides the definition for the selected word.

If you aren't running KDE or if you prefer a simpler approach, may I interest you in a lightweight, text-only client that does a similar thing? It's Vishal Verma's edict; I wonder if he looked that word up in the dictionary. You can get edict from edictionary.sourceforge.net. The edict program is nothing more than a Perl script, but it does the job quite nicely. In terms of installation, there really isn't much to do after extracting the tarred and gzipped bundle. You can run the script from the directory in which it was extracted, but you'll more than likely want to run a make install to save the script to /usr/bin.

To run the program, type edict followed by the word you want to look up. For a synonym lookup, type ethes followed by a word. If the word you are looking for isn't found, alternatives are offered.

The ethes program is simply a symbolic link to edict. Consequently, a thesaurus lookup is essentially the same process but with different results:

[marcel@mysystem edict]$ ethes program edict - Your personal command line dictionary. Verison 1.0. Looking up "program" in Merriam-Webster Online Thesaurus... Entry Word: program Function: noun Text: 1 a formulated plan listing things to be done or to take place especially in chronological order <the program of a concert> Synonyms: agenda, calendar, card, docket, programma, schedule, sked, timetable Related Words: bill; slate; plan Idioms order of the day 2 Synonyms: COURSE 3, line, policy, polity, procedure

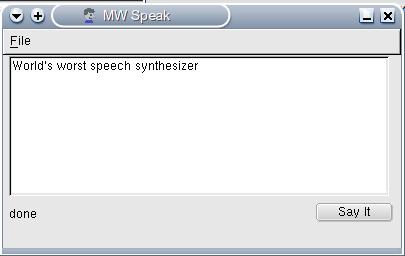

Speaking of dictionaries, what is there to say about speaking dictionaries? More to the point, what is there to say about Jeffrey Clement's MWSpeaker, which he describes as the “worst speech synthesis software ever”? Those are his words, mes amis, not mine. The idea is simple, if not a bit silly. You type in a word or a phrase and MWSpeaker reads it back in human speech. The speech in question comes from the Merriam Webster Online Dictionary. In short, it finds each word's corresponding wav file, downloads it and plays it in sequence.

Given that MWSpeaker is a Python script, it requires no compiling per se. Simply download the program from www.jclement.ca/Projects/mwspeaker, then unpack the tarred and gzipped bundle. Before you actually can use the program, you need a few additional packages, most notably wxPython, pygame and PythonCard. To run the program, cd to mwspeaker-1.0 (where you unpacked MWSpeaker), and type the following:

mkdir data python mwspeaker.pyw

The data directory is where the wav files are stored. The GUI is simple. Type a word or phrase, click Say it and wait. I say “wait”, because MWSpeaker downloads each word's wav file in turn before playing your selection. The results can be a lot of fun because the voices saying the words aren't consistent. You wind up with a strange mix of male and female voices.

Figure 3. The Self-Proclaimed World's Worst Speech Synthesizer

All this is wonderful for the English language, but Linux and open-source developers come from every part of the world, after all, as do Linux users. It is true that an English language dictionary is useful to those who don't count English as their first language, but sometimes you must translate.

François, remplisser les verres de nos invités, s'il vous plâit.

To translate French (or Italian, or Spanish, or German and so on) into English, you might find yourself looking for a Babel Fish. What is a Babel Fish, you ask? According to Douglas Adams, the creator of the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, it is a small yellow fish that, when put in your ear, simultaneously translates any language you hear into the one you normally speak. But as Douglas Adams wrote, “Meanwhile, the poor Babel Fish, by effectively removing all barriers to communication between different races and cultures, has caused more and bloodier wars than anything else in the history of creation.”

KDE's combination web browser, file manager and Swiss Army knife, Konqueror, has hooks built in to AltaVista's Babel Fish. Surf on over to a foreign language web site, and you easily can translate the information you find there. For my example, I randomly picked a German language newspaper, Die Welt, which I learned means “The World”.

When your page has loaded, click Tools on Konqueror's menubar, select Translate Web Page, then select from one of the language selections in the drop-down list. In my example above, I chose “German to English”, et voilà! You now can read the information in a language that makes more sense to you.

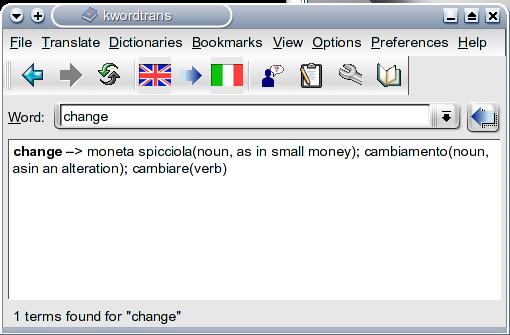

For your own personal and local translation dictionary, you may want to consider taking a look at Ricardo Villalba's wordtrans at wordtrans.sourceforge.net (Figure 4). Compiling wordtrans can be a little tricky, but it isn't a great problem. A visit to TuxFinder (www.tuxfinder.org) turns up quite a number of precompiled packages. I downloaded both the base wordtrans package along with the wordtrans-kde packages in RPM format and installed them. If you are downloading packages, you do need both. You may also find a wordtrans-qt and a wordtrans-web package.

Figure 4. wordtrans, Your Personal Translation Dictionary

By default, wordtrans comes with English, French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish translation dictionaries, but more can be added. You'll find links to other language files on the wordtrans web site and in the software itself. When you start up Kwordtrans, it may appear as though nothing happened, but look at your system tray in the Kicker panel and you'll see a little gray book icon. Click here and the Kwordtrans interface appears. To select your language of choice, click Dictionaries in the menubar and choose from the list. Choose the direction of your translation (for example, English to Spanish or Spanish to English), type in a word and press Enter.

As I mentioned, you can add additional dictionaries by clicking View on the menubar and selecting Introduction for some links. This not only extends wordtrans' capabilities, but some of the dictionaries available for download are more extensive than the default ones. To add a downloaded language file, click Dictionaries on the menubar, select New and follow the instructions. I downloaded and installed several from www.linuks.mine.nu/dictionary with excellent results.

I'm afraid I do not speak Hungarian, mes amis, but apparently I would have to say az idõ lejárt, which my desktop translator tells me means “time's up”. It is indeed closing time, but there is time enough for another glass of wine before you go. Raise your glass and my faithful waiter, François, happily will take care of you. As you can see, with a little exploration in our Linux kitchens, we may one day be able to communicate effortlessly with the world. Until next time, mes amis, let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé! Bon appétit!