Robin describes how Shake on Linux is used to composite special effects.

Video compositing software is used by motion picture studios to combine special effects or animation elements into film sequences. Compositing software may be thought of as doing for moving images what tools like the GIMP and Photoshop do for still images. Nothing Real's Shake seems to be the most widely used high-end compositing package today. Shake runs on Linux, Windows and IRIX, and Apple has just confirmed rumors that it has acquired Nothing Real and Shake.

Tippett Studio specializes in scary effects, such as bugs and creatures. Let's visit Tippet Studio in Berkeley, California for a look at how they use Shake on Linux.

As a visual effects and animation studio for feature films, Tippett Studio has won Academy Awards for visual effects work on Return of the Jedi and for Jurassic Park and was nominated for effects in Starship Troopers, Dragonheart, Willow, Dragonslayer and Hollow Man. Tippett Studio currently is creating effects for the vampire movie sequel Blade II (release March, 2002). “We've been using Shake on Linux since Evolution, about a year and half”, says compositing supervisor Alan Boucek. “I'm running Shake on a dual Athlon. What's exciting is that it is so fast. I can mostly work on my own machine, without going to the renderfarm.”

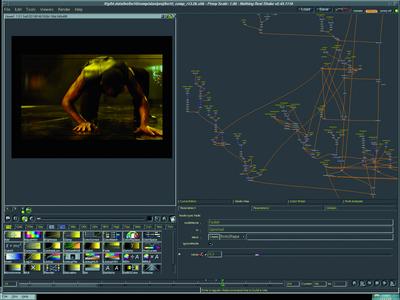

Shake being used to composite a scene with Wesley Snipes in Blade II. Window manager is MWM for continuity of look and feel with SGI IRIX workstations.

Boucek adds that his compositing crew was the first in the studio to move to Linux. “Once we got Shake up and running, the next task was to get our pipeline on Linux”, he says. “For most of our 3-D rendering, we use Pixar's RenderMan. Grey renders are straight out of Maya, but animators run their stuff through a simple Renderman pass for daily review.”

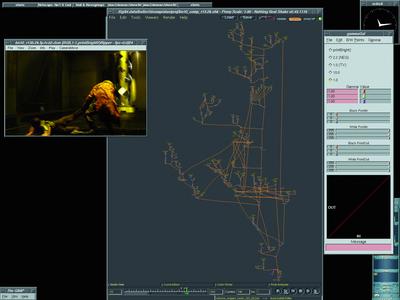

Shake uses a tree-graph interface to manipulate effects. Each input is passed through nodes that represent filters or transforms that create the final composite images. Complex effects take longer to render, and time is always at a premium at a studio. Special effects artists often work at quarter resolution in near real time with Shake on a workstation, then later batch process the effects at full resolution on the server renderfarm.

Two years ago when Tippett needed new computers for compositing they chose $5,000 US SGI x86 PCs over $24,000 US SGI Mips Octanes. “We bought SGI PCs at first, but after those were discontinued we started building our own machines from scratch”, Boucek says. “We've saved a lot of money on machines, but a lot of that is taken up in providing our own support.” Besides PC and SGI computers, they have many Macintoshes. And, some of the PCs are running not Linux but Windows versions of Shake and 3-D modeling package Maya. Boucek prefers Linux:

We can't tie NT into our renderfarm. When we go home at night the Linux boxes keep working. The NT workstations are dead—can't do double duty as renderfarm servers. We still have a lot of SGIs. Our Linux software conversion is just completing.

“Just being able to talk to who wrote the original code is a tremendous advantage”, says Director of Technology Christian Rice.

With Linux we can have a personal dialogue with the author of a package in a noncorporate manner. We've overcome several hurdles in that manner. It does create more responsibility for us though, and more uncertainty. Just because a search of the Web turns up nothing doesn't mean something can't be done. Talking directly to the developer often gives us an insight into special features that we wouldn't otherwise be aware of, not to mention special features being implemented to accommodate us.

“Writing plugins for Shake at the beginning is very hard”, warns Software Engineer Qin “Jean” Shen. “There isn't complete developer's documentation. I would copy a simple example from the dev kit then send a lot of e-mail questions to Nothing Real as I worked on extending it. They are good about replying and helpful.” Shen explains that Nothing Real tries to write good documentation, but because each plugin serves a special purpose it is hard to be comprehensive. Plugin developers must take care to note when something is needed in memory so that Shake can automatically fetch it. “Shake is a scanline renderer”, notes Boucek. “It doesn't read the entire image in memory at once. That's what makes Shake so fast.”

Shen disproves the theory that you can't get an exciting job in motion picture software development right out of college. Although she already had an offer from nearby ILM, she choose Tippett because as a smaller studio it offered her more involvement. “When I started in 1999 we were still using Alias|Wavefront Composer. I wrote plugins for that, and then Shake after we switched.” Shen works on development of Flipper (a flipbook movie player) and GammaGal (a tool to adjust monitors), both internal tools. “Flipper and GammaGuy had been written using Motif and IrisGL. I rewrote those in OpenGL and FLTK, and GammaGuy became GammaGal.”

Shake preview on left during split screen transition. Flipper flipbook player on right. Icons (lower left) are for in-house plugins.

Flipper on left, GammaGal on right. Flow graph in Shake to build one entire movie shot (scene).

“An important feature in Photoshop is gamma-level adjustment”, explains Software Developer Darby Johnston. “GammaGal allows us to do something similar very quickly on IRIX and Linux.” Because film has a greater dynamic range than do video monitors, users constantly must play with levels to see details in dark or light areas. Artists working in film play with gamma like an artist will play with magnification while retouching a still image.

“To describe our Linux efforts converting our IRIX tools as porting is too strong a word”, says Johnston. “For the most part, stuff just compiles.” Johnston's work involves mostly traditional C-style coding, without threads or shared memory. Johnston is part of a team writing glue code for integration, an image-processing suite (e.g., blurs, crops, scales) and batch tools.

“There still are growing pains with Linux”, notes Boucek. “A lot of development in Linux seems to be about beating Microsoft. But, what we need is a reliable platform that runs our tools.” When Tippett started with Linux, the NVIDIA drivers were still in beta and had problems. “Sometimes it wouldn't draw a line in glLines correctly”, says Shen. “I used glStrip instead as a workaround. We had many instances like that.” Boucek adds, “A lot of instability in the early months with Linux was tracked down to the NVIDIA drivers, and Maya is still pretty unstable for us on Linux using NVIDIA GeForce2 and Quadro2 graphics cards.” Despite problems, NVIDIA drivers have been key in the transition to Linux.

“The performance of the proprietary NVIDIA drivers has been important in spurring our move to Linux, although we can tell that the optimization effort is toward Quake more than 2-D”, says Johnston.

We recently tested XiG with an ATI RADEON 7500 on a 1.4GHz Athlon and found it much faster for 2-D. Flipping frames at 1,920 × 1,200, the NVIDIA drivers barely hit 30fps, but the XiG drivers were over 40. However, in 3-D the NVIDIA drivers were perceptibly faster in Maya.

“We're trying hard to get Linux on everyone's desktop”, says Boucek. “But, we're still not there because of stability problems with Maya on Linux.” Boucek wants to see Linux and Linux drivers continue to get more stable and for performance to improve.

Square is another movie studio that has done stunning work using Shake, on the motion picture Final Fantasy. “We started with IRIX four years ago”, says Visual Effects Supervisor James Rogers. “Our Linux renderfarm was brought up in the middle of production.” Square used their existing IRIX boxes for workstations, then sent data through a custom render manager to Shake batch render on the Linux renderfarm. “We started testing Linux workstations at the end”, says Rogers. Square recently announced it will cease movie operations and close its offices in Hawaii as of March 29, 2002.

To install Shake we download three files (55MB) from the Nothing Real web site: the license manager (lmutil.Z, 184k), the application (shake-linux-v2.46.0116.tar.bz2, 28MB) and the tutorial (shake-tutorial-v2.46.0116.tar.gz, 26MB):

gunzip lmutil.Z tar xvfj shake-linux-v2.46.0116.tar.bz2 tar tvfz z/shake-tutorial-v2.46.0116.tar.gz tar xvfz z/shake-tutorial-v2.46.0116.tar.gz ./lmutil lmhostid

Just to double-check, we used the tell switch with tar to see what it would do before doing an extract.

The lmutil program echoes a 12-digit license-manager host ID. This host-locked ID code must be sent to Nothing Real in order to receive a two-week trial key code (key.dat). Copy the e-mailed key to the specified directory, start X and run Shake:

cp key.dat shake-v2.46.0116/keys/ startx shake-v2.46.0116/bin/shake

Unless you already know Shake, two weeks isn't much time to learn about this complex tool.

As this story is being written, the future of Shake is unclear. Apple confirmed rumors of the Nothing Real acquisition in a short statement released on February 6, 2002. Tippett Studio's Boucek notes:

They have a core renderer that's faster than anybody's. That could be valuable in QuickTime or Final Cut Pro. Shake is such an important tool for us on Linux we have to be concerned about what would happen if it becomes OS X only. But, it would be good if it was cheaper so we could afford more seats. In general, we're excited about OS X. We have a lot of Macs here.

With BSD-based OS X, the Apple platform gained NFS and other UNIX features that help it integrate into movie studio pipelines.

Apple, in a two-sentence statement confirming rumors that it had purchased the company, only revealed that it “plans to use Nothing Real's technology in future versions of its products”. In 2001, Nothing Real had announced that it would port Shake, which runs on Linux, Windows and IRIX, to Apple OS X. However, Apple is uncommitted as to whether it will release that promised OS X version of Shake.

Since Apple has never continued development of a GUI application for another OS after an acquisition, it seems this may be the last version of Shake for Linux workstations. However, the Shake renderfarm server software will probably continue to support Linux indefinitely. There's a precedent with the Apple Linux Darwin QuickTime server software. If future versions of the Shake GUI only run on Macintoshes, the extra hardware cost for new Macs seems a nonstarter to studios. But, Apple could sidestep that by lowering the cost of Shake. At nearly $10,000 US per seat, Apple could throw in a loaded $2,000 US iMac for free.

Some studio managers are feeling spooked by Apple's total silence on their plans for Shake. But others, such as Boucek at Tippett Studio, express optimism that Apple has something to offer to the professional motion picture editing market.

Because that's been most of the market, Linux companies are more focused on servers than workstations. Despite not really being designed for that, Red Hat is the de facto standard for Linux workstations. Some users say server-oriented Red Hat is not a good distro for the desktop. Red Hat CEO Robert Young admits being booed more than once for telling Linux crowds, “Linux will never be successful on the desktop.” Competition from Apple OS X may spur Linux to become more user-friendly. Thanks to OS X, Apple system Software Product Manager Ernest Prabhakar was able to announce at USENIX BSDCON in February 2002 that BSD is now three times more popular than Linux on the desktop.

Apple may shake up the motion picture effects business. Steve Jobs is the CEO of both Apple and Pixar. Or, up-and-coming competitor Silicon Grail's RAYZ could be a big winner as a result of the Apple's Nothing Real acquisition. Many studios are taking a hard look at RAYZ due to the uncertainty surrounding Apple's plans for Shake. We'll take a look at RAYZ on Linux in detail here next month.