The author demonstrates how easy it is to write in Python—and make sure you get steamed, not fried rice.

Maybe this article should be entitled “How I Discovered Python and Ditched Everything Else”, instead. I have always wanted to write web-based applications but somehow found that getting started was quite intimidating. So, having procrastinated for years, I finally got around to writing my first application. My work required an intra-office application for which some values needed prompting on a web page. These values are sent to a CGI script, cross-verified via an SQL database, dispatched to a waiting process via sockets, and the results sent back to the web page.

By luck, I stumbled upon a scripting language called Python. I was reading a recent issue of Linux Journal (December 1999), in which they interviewed Eric Raymond, who mentioned that he now programs only in Python. At that point, I was a day into implementing the above system in Perl and was not quite finished. If Python was good enough for Eric, it was worth a try.

Well, I finished what I wanted to do in just over two hours. This was using a language that I had not heard of two hours earlier. At the risk of losing my professional advantage, I thought I would share with others how easy Python is to use, especially to do CGI (and almost everything else). As the above application would be too technical and boring to actually work through (and I'd probably get sued by my employers), I've decided to work through another, much more interesting exercise.

Work being situated in a semi-remote location (culinary-wise, except for the place next door, which has excellent food but is a bit expensive to eat lunch at every day), take-out lunch was organised to be delivered to us once a week. Each participant took turns organised the lunch orders. Being spread out over three floors, it was quite a chore, and no one looked forward to doing it. A web-based ordering system seemed to me the obvious solution but not having done any CGI programming before, it seemed quite overwhelming. The others did not seem to care. But writing CGI web systems can be quite simple, especially when one can do it using Python. (Okay, Perl gurus may disagree, but that's the whole point, i.e., a Perl guru versus a Python novice!)

I knew roughly how I wanted it structured. There'd be a web page with a pull-down list with the restaurant menu, and, by clicking on a submit button, an e-mail with the person</#146>s order would be sent to the nominated lunch organiser.

Based on hearsay and some cursory research on the Net, I decided to use the following tools:

Javascript for the client end (the web page)

Python for the server side

Apache for the web server, which is distributed with Linux (well, it was with my copy of Red Hat Linux 6.2); there is also a Windows version, too, if one is so inclined

Linux for the web server OS

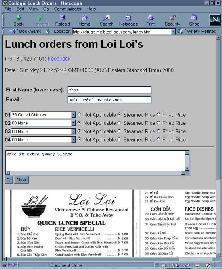

In designing the web pages, I decided to keep it fairly simple: a pull-down box with some radio buttons (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Snapshot of lunch.html

I could have used some HTML editor but decided that I could not handle learning another new package, so I did it by hand. Since what I wanted to do wasn't complicated, the by-hand method proved sufficient.

It was easy to install the web server using Linux. When I was installing Linux, the option to install Apache was ticked. When I typed in localhost as the URL to Netscape, it displayed the Apache page with the message that if I saw that page, everything was A-Okay! Whoo-hooo... so far so good. (See http://www.apache.org/ for more details). You'll probably need to be root (the superuser) to do the install.

Using Javascript to write a web page seems semi-obvious. There are several functions for data input verification (ValidLength() and ValidEmail()). MenuHeader() displays the header part of the page. Each call to MenuEntry() displays an input row. In this case, it is called four times, once for each lunch order item (see Listing 1).

The most tricky lines would be the ON-SUBMIT statement:

<FORM NAME="order" onSubmit="return Validate();"

ACTION="http://localhost/cgi-bin/lunch.cgi"

METHOD="POST">

There are two ways a web page can communicate with a CGI script: GET and POST. In a nutshell, GET sends the information as part of the URL (i.e., you might have seen some URLs which resemble http://localhost/script.cgi?param1=value1¶m2=value2 in your surfing of the Internet). When POST is used, the form information is sent via the standard input, i.e., the CGI script needs to read in standard input, and then parse the input separate out the various parameters.

It is generally accepted that POST is better (more robust, not limited by the maximum character limit of shell used). The methods used to extract the data differ according to whether POST or GET is used, but Python hides this from you (which is good).

I then placed the lunch.html file in the directory /home/httpd/html:

$ cp lunch.html /home/httpd/html

(This is the default location Apache looks for html files. It can be configured to look elsewhere.) Once you have done this, you can see what lunch.html looks like by browsing http://localhost/lunch.html using Netscape (or any browser).

Write the CGI script with Python, which is distributed with the Red Hat Linux distribution (see http://www.python.org/). After consulting the Python documentation, which also came with the system, my first script looked like the one shown in Listing 3. It is essentially a cannibalised version of an example found in the Python documentation. To make use of this script, you'll need to point the CGI script specified in the ACTION statement in the HTML file to this script instead. That is, change the cgi script specified in the ACTION statement from lunch.cgi to first.cgi.

I then copied first.cgi to the directory /home/httpd/cgi-bin:

$ cp first.cgi /home/httpd/cgi-bin

Essentially, I interrogated all the variables sent to the script by the form and printed it back out. All output printed will be displayed by the browser.

#----------------- 1 #!/usr/bin/env python 2 # first.cgi 3 import cgi # import the cgi module 4 5 print "Content-Type: text/plain\n\n" # necessary for the browser 6 7 lunchForm = cgi.FieldStorage() # retrieve the values 8 9 for name in lunchForm.keys(): 10 print "Key= " + name + " Value= " + lunchForm[name].value + " " 11 12 print "bye." #-------------When the Go button on the lunch.html page is clicked and the first.cgi script is activated, the output returned to the web browser looks like that shown in Figure 2.

You will notice that the keys found in the CGI script correspond to the variables I used in lunch.html.

Once I got this simple script working, I then expanded it to do what I wanted (see Listing 3). The Python code is quite straightforward and self-explanatory. It imports the CGI module, then calls the member function FieldStorage() of CGI. Whether the information is sent using the GET or POST method is hidden from you. That's how all the information sent by the web page is retrieved. The information can then be extracted by accessing lunchForm.

The body of the mail sent is then constructed via a series of writes to sendmail, a UNIX sendmail mail transfer agent. I decided to mail the lunch order to user lunch@localhost. An alias can be inserted in file /etc/aliases:

lunch: chai@localhost

where user chai@localhost is organising the orders. This way, if the lunch organiser gets changed, the file /etc/aliases needs to be changed and not the CGI script. (newaliases needs to be run for changes to /etc/aliases to take effect).

Easy, eh? Well, it could be much worse.

I then copied lunch.cgi to the directory /home/httpd/cgi-bin:

$ cp lunch.cgi /home/httpd/cgi-bin

I opened Netscape, typed in http://localhost/lunch.html as the URL, filled in the form, selected my order and clicked on “Go”.

Sometime later, an e-mail arrived outlining the order.

Here is what the received e-mail of the lunch order, sent by the CGI script, looks like:

>From nobody@localhost Wed Apr 26 11:01:50 2000<\n> Delivered-To: ccang@localhost Date: Wed, 26 Apr 2000 11:01:48 +1000 To: lunch@localhost From: chai <calcium@altavista.net> Subject: loi loi Sender: nobody@localhost SourceIP 194.118.1.1 calcium@altavista.net Wed Apr 26 11:01:01 GMT+1000 (EST) 2000 chai wants 1. L39 with Steamed rice. 2. NONE with NA rice. 3. NONE with NA rice. 4. NONE with NA rice.

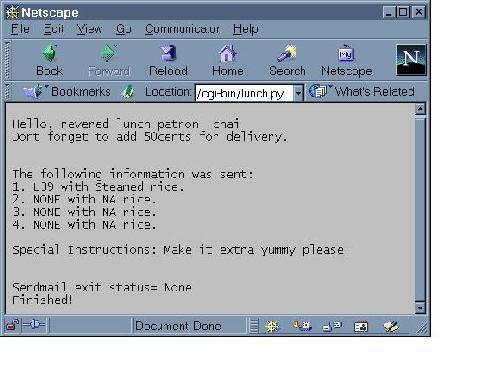

Figure 3 shows what the web page looks like after the request has been sent.

Figure 3. Snapshot of Resulting Web Page After Lunch Order Made

Is the on-line system better than write-order-on-scrap-paper method? Debatable, but it certainly is more fun (at least for me).

Improvements? The web page is geared towards an individual making an order, as opposed to a person ordering for multiple people. In hindsight, the web page could have been laid out with the latter in mind, and, being a superset of the former, would satisfy those requirements as well. A simple compromise could be having a multiples box, which would allow a person to order more than one serving of the same dish per order row. In the current scheme, this would still only allow four different orders per e-mail. So make it 10? 20? How long is a piece of rope? (paraphrased to make it more sinister). A design problem left to the reader.

I suppose I could also hook it into an SQL database (http://www.mysql.org/) and print out a histogram of the past orders for a particular person. A by-product of using a database is that one could print out reports, e.g., what is to be ordered for that week.

I suppose if there is enough interest and if I have enough time, I'll add a second part to this system, where the CGI script would interact with a SQL database and return HTML code to display a frequency list. And, perhaps, with some cookie interaction.

Finally, on a personal note, I've seen the future and it is Python. Look it up (and JPython too!).