You'll feel much better after reading about this new cross-platform toolkit written in Python and wrapped around wxWindows.

To many people in the “real world”, MS Windows is an inescapable, however unfortunate, fact of life. Some of these people might even have clients or bosses who require a “standard” Windows GUI application at the end of the day. For many developers, being able to choose the best tool for the task at hand, rather than being told which one to use, is an essential element of their quality of life, and Linux is a pleasant development environment.

It is in fact now possible to do quality, rapid GUI development for Windows on Linux, and is becoming increasingly possible for other GUI systems as well, such as Apple Macintosh, BeOS or OS/2. One of these tools, which I present in this article, is wxPython, which is not only based upon a proven toolkit, wxWindows, but uses our favorite language, Python.

There is no lack of choice of GUI development systems or toolkits under Linux, and quite a few of them can be called portable, i.e., work on at least two different platforms, for example, Linux/UNIX+X11 and Windows. Many of them are free, but not all of them are in usable form (i.e., documented, maintained, relatively bug-free and feature-rich). However, we are fortunate that such tools do exist. In fact, a well-maintained web page, http://www.free-soft.org/guitool/, lists an impressive number of such toolkits. The problem is deciding which one to choose, since life is too short to try them all.

Life is a series of compromises. Often, the problem is finding out which set of drawbacks one is prepared to live with in return for which benefits. For one of my projects, I finally settled on the following list:

compatible with Linux, Windows and Python

usable

large enough widget set

not too slow

compact

easy to learn

converts to C/C++ easily after prototyping stage, if necessary

looks good

At the time of this writing, wxPython is in release 2.1.13. Its author, Robin Dunn, has done a very good job of wrapping up wxWindows, one of the classic C++ GUI tool kits that has been around for several years. As a result of its relatively long existence and popularity, wxWindows has been ported to a number of toolkits and platforms and enjoys a relatively large widget collection. For Linux, the version of wxWindows that wxPython uses is wxGTK, the wxWindows interface to the GTK. For windows, the wxWindows port to win32 was used.

The interface of wxWindows to Python is remarkably transparent. The concepts are the same and the naming conventions are mostly the same. The object-oriented nature of the toolkit has been preserved. If you know how to program in C++ with wxWindows, you will have no problem with wxPython. Conversely, if you have a working proof of concept in wxPython, porting all or part of it to C++ for better speed should be straightforward.

wxPython is quite compact, but doesn't come with the standard Python distribution. See the Resources section on where to get the software. I found wxPython easy to learn; the distribution comes with a huge series of helpful demos which I will use in examples.

All of wxPython is open source, so people can contribute and fix bugs. In general, the software quality is high.

For all its qualities, wxPython does have a few minor drawbacks. As of this writing, the wrapping of wxWindows is not complete, but Robin Dunn and others are working on finishing up.

The documentation is both very complete and almost non-existent. Robin can get away with this because wxPython is so similar to wxWindows that the wxWindows documentation, which is quite good and complete, can be used instead. The Python-specific part of the documentation is reduced to a small number of notes within the text (if a feature is not available or slightly different, for example) and a small section toward the end of the documentation. It is hardly any effort to do the mental translation from C++-type calls to Python, but if you've never seen C++ code in your life, this can be seriously off-putting.

The product is still very much in development. It follows wxGTK quite closely, but the wxGTK version it is based on is an unstable, development version. This means a number of things may not work perfectly, and things are likely to change a lot from version to version. I've had a lot of problems with printing under Linux, whereas it works perfectly under Windows.

wxPython would probably benefit greatly from a step-by-step tutorial. By the time you read this, someone will most likely have written one.

An interactive GUI-building tool would also be of interest. I understand that reusing the one from wxWindows should become possible soon.

The installation of wxPython is fairly straightforward if you have a Debian or an RPM-based system, as Robin Dunn provides both of these packages on his web page at http://wxpython.org/. You'll need wxGTK installed (again, a package is provided) as well as Mesa-3.0.

We are now going to look at some simple wxPython examples. The intention is not to offer a tutorial but to get a feel for the way wxPython can be used.

The obligatory “hello world” application is shown in Listing 1. A fixed-size frame is created at line 14. A panel is attached to the frame at line 18, and within the panel, a static text area displaying “Hello world of wxPython” in the default font is created in lines 19-20. The application subclass definition is shown on lines 23-32. An instance of our frame is created, shown and brought to the foreground. If these definitions are run stand-alone, rather than being imported in another application, an instance of an application class is defined and run in lines 36-37.

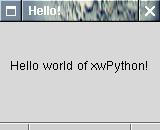

Note the systematic use of the object-oriented framework even in this very simple example. The frame and the application are subclasses of the pre-defined classes. We need to redefine only the methods we use to get our program working. A screen shot of this impressive application is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. ScreenShot of the “Hello” Application

One might say that about 40 lines of code is too many for a simple application that basically does nothing. In fact, you could probably cut this down to a few lines, but the goal is to present a relatively well-structured piece of code which is easy to build upon.

There are many function calls with -1 given as second argument, such as panel = wxPanel(self, -1). In these cases, the value of -1 is a mandatory numerical identifier for the object being created, which is used when connecting widgets together, as we will see in the second example. A value of -1 means “default” and is useful when this object ID will not be used anywhere in the code.

In the previous example, the position of the widget in the window was fixed, and we had no control over the application other than through the window manager: no menu, no exit button, etc. Moreover, getting the “hello world” message is a bit boring, so here's an application that does more and is much longer. The application is shown in Listing 2. In this second example, the structure of the program is essentially the same: we have a subclassed Frame and a subclassed Application. The subclassed Frame redefines the __init__ function. In the redefined __init__, we define a few more interesting messages than “hello” on line 13-18, a counting variable on line 19, a menu table on lines 20-25. As before, we call the parent's __init__ function on line 27, create a panel on line 30, some static text field on line 31 and a button on line 34. Lines 36-43 are devoted to the layout of the main part of the window. Basically, we have the static text in a fixed position; underneath it is a button, at the bottom of the window, that remains centered with respect to the right and left part of the window, no matter how wide the window is. This is done using a number of wxBoxSizer objects. On line 45, we associate a button event between the button defined on line 42 and the OnButtonClick method defined on line 69. This method will be called when the button is pressed.

On line 47, we associate the application close event with the OnCloseWindow method, defined on line 76. Using this method, we build a quick message dialog box to ask the user for confirmation. On lines 48-64, we create a status line where the menu tool tips will be displayed. The main menu of applications is defined by the specs in myMenuTable, lines 20-25. Note that the “New” menu item will also call the method of line 81. In the definition of the menu items (lines 24-29), the character & before a letter indicates a keyboard shortcut (typing ALT + the letter calls the menu item).

On lines 65-67, we make the window layout fit together and set the autofit feature of the wxBoxSizer objects “on”. Lines 69-72 define the callback method from both the menu item and the button. This method simply redefines the text content of the static text object defined on line 31. Pressing the button multiple times shows the strings defined in self.myFortunes, line 13-18, in succession. The method of lines 87-88 is called from the “Exit” menu item and invokes the Close event, which will close the application. Lines 90-106 are identical to the “hello” example. A screen shot of this application is shown in Figure 2.

The more interesting points of this “toy” application are how window layout can be achieved (using wxBoxSizer) and how events and widgets are connected (using EVT_MENU and EVT_BUTTON in this case). In fact, as it is, only the layout of the button is satisfactory; the main text is still in a fixed position—a complete solution would be too long to show here.

Note the use of the self.something variables. If a variable is to be accessed across methods, it must be called in this way (self being the object instance). If a variable is private to a method, the self prefix is not necessary.

As mentioned above, a complete tutorial to wxPython is not ready yet, although one is on its way. Nearly all the widgets supported by wxPython are demonstrated in the demo application that comes with the distribution. Since the examples are concise and to the point, it is possible to learn from them fairly quickly.

At the moment, we are enjoying a growing array of usable tool kits, and I feel wxPython is one of the better ones. Like most things written in Python, programs in wxPython tend to be compact, easy-to-read and maintain and powerful. The range of available widgets doesn't match MFCs (Microsoft foundation classes), but is adequate for most applications. I personally find that this particular tool kit makes the RAD (rapid application development) concept finally available to Linux. The fact that applications written in this framework also work on Windows will be a tremendous benefit for some.

As it stands, wxPython probably cannot replace Tkinter as the default Python GUI tool, at least not until the Apple Macintosh port of wxWindows is completed and a stable release is made. But it shows a lot of promise, as being a much higher-level toolkit.