There must have been some magic in that old grey box...

This month, “Games Focus” moves out of upFRONT and stands on its own as “Games We Play”. Last month, we went a little nuts, or rather I went a little nuts, over emulation of the arcade games we used to play in pizza parlors, roller rinks and video arcade joints. Those games were really fun, and honestly, every time I look at the new ones coming out, I think to myself how happy I am not to be in the video-game industry, because the coding involved in the crazy 3-D things done in these games is too complicated. How do you figure out which parts of an object are sitting behind the others, and how the light and shadows fall? Those old games were really neat, and some day, when you've got a gigantic flat-screen monitor, you can have your own at-home video arcade. Sit on a sofa, drink iced tea and fire up the old video games on your wall (of course, we'll have wireless controllers, too). Ah, the good old days, er...

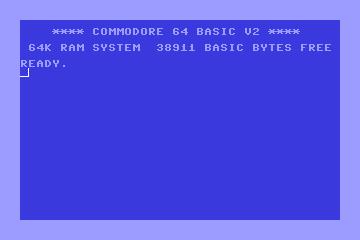

As there is another Skywalker, there is also another area of emulated games. The Commodore 64, as many of you will remember fondly, is an 8-bit computer based on the 1MHz 6502 processor, which is now emulated quite well on Linux. It was wildly popular and fun to hack. It came with BASIC, but you could get a cheap assembler anywhere and start exploring exactly which bits did what. In fact, you could just use the BASIC command POKE to upset bits all over the place, often leading to disastrous effects. Recite numbers like 64738 or 53281 to some old C64 user, and you're sure to get a rise. Unlike Linux, the C64 was a single-user machine that was effectively in root all the time and functioned very well for real-time demands such as video games. And that brings us to the point.

Commodore 64 games are now available for you to play again on your Linux box. They are exciting, with a feeling unlike any other computer games. Unlike the emulated video arcades, where you can play roughly 2,000 games, the C64 emulators open the door to over 10,000 games as well as countless demos (if you don't know what these are, you should have a look) and other odds and ends. Of course, these games were a bit odd (programmers had more free reign to express themselves in home computer games), often with lower-quality graphics than the coin-ops and much more interesting and creative game play. Remember, many of the best games simply aren't suited for coin-op arcades because they're slightly long term. Indeed, computer games were once for those with longer-than-a-quarter attention spans. One thing I find particularly amusing is to go back to those old chess programs that infuriated my eight-year-old self, and beat on them mercilessly (they were scary; Sargon even came on a sinister red disk). Well, chess is one long-term game, but RPGs (role playing games) go on far longer. Anyone for Bard's Tale or Ultima? The AD&D (Advanced Dungeons and Dragons) series from TSR Strategic Simulations (a division of Interplay)?

There was nothing new for Commodore 64 gamers when games like Mortal Kombat hit the streets. Years before, C64 folks had played the original combat games, such as Melbourne House's Kung Fu (Way of the Exploding Fist) or Epyx's International Karate+. More creative martial-arts games were available, including classics such as Bruce Lee, Yi Ar Kung Fu (with the protagonist Oolong) and countless others. It was also no surprise when, years later, Sid Meier rose to stardom in the PC world on his Civilization series; Sid was already a longtime hit with C64 fanatics for ingenious masterpieces such as Pirates! And, it was nothing new for the C64 crowd when Lord British went on to celebrity status with his Ultima series (in its current incarnation as Ultima Online). These chaps have been around forever, so it has been a nostalgic surprise to see them featured recently in magazines—video game designers, fancy that!

Current hackers, especially hacker historians (if such animals exist), techno-cultural anthropologists and other similarly interested folks have another value for this software; that is, the historical-cultural value. Linux hackers often claim lineage dating back to UNIX and whatnot, but the fact is, we can't all have come from UNIX. Someone must have been from that generation to whom BASIC was a language and for whom computers were single-tasking bit boxes. Indeed, the excitement of the early personal computer revolution had little direct involvement in UNIX; it was the Apples, Commodores, and to some extent, the IBM PCs (while some may even remember the Spectrums). The C64, for whatever reason, attracted more ingenuity and technical exploration than the others, and developed its own extremely vibrant and enthusiastic scene (which later migrated to Amiga). Even with software that didn't cost very much and fewer users than the computer world has today, Commodore somehow inspired seemingly limitless creative energy and development.

Commodore 64 software relates to a time before the Internet, before hard drives, before open source, before free software was popular, before compilers, before networking. Although these things existed, they didn't affect the C64, since we didn't have the resources for anything more than short machine-code programs. The culture was much different then, with software houses pumping out games high in playability and imagination, low on resources and abundant in programmers able to express themselves in their wares. (The computer community was much brighter and more creative than today's mainstream Windows world, so it was also more receptive to creativity.) After watching many people make a fortune on commercial software, groups of teenagers sprung up around the world, oriented around trafficking unauthorized copies of software (struggling to be the first to break the copy-restriction schemes, which were actually very harmful on the disk drives), writing intros and demos, maintaining contacts and hosting enormous demo competitions and copy parties. Demo writing, in particular, often overshadowed the cracking activities. Some relics of this culture survive even today, but the Net has largely homogenized the modern computer world. Those curious about the cultural history of '80s hackers (when hackers broke into computers, crackers broke software restrictions, and coders wrote code) could find much of interest in C64 wares, especially the demos, intros and “cracktros”.

Demos would demonstrate what the machine was capable of and what the coder could contrive to do. Typically, demos contained scroll texts full of greetings (which you may remember from early episodes of “Stupid Programming Tricks”), star fields (essentially little white pixels that moved), music (known as SIDs on the C64) and some graphics or other animation. What was outstanding, of course, from a technical standpoint was how far these cats could push the computers. Just try sitting down at your Linux box and writing a demo with a sine scroller (text that warps like a slithering snake), music, star fields, animation and a background, and you'll probably take up more than 1MHz of your system's resources. Now try doing that in 6502 assembly code in the days when there were no easy graphics libraries and no one shared source code. (Because, if you knew how to do what other people could do, you'd be just as cool as them; hence, they never gave away their secrets.) In fact, the horrible secrecy surrounding source code sharing meant everyone had to figure out everything for themselves, which wasted a lot of time. (Admittedly, this problem was much more severe in the states; European sceners were usually better about sharing.) Often, people would “trade” programming tricks the way many traded cracked software; you'd have to give the code to something cool, or they wouldn't help you out. It seems quite selfish; well, that's the culture of the '80s. At least I can say I have always shared code...

Intros and cracktros were small demos which often didn't do anything enormous or particularly outstanding outside of the basic music and scroll text, with some small additions, usually for the purpose of saying “So-and-so cracked this game, we're so cool, megagreets to so-and-so, such-and-such, who-and-who, et al.” and maybe with some insults to their schoolteachers or bus drivers (strangely, for really smart kids, school is usually a nightmare). Intros are quite interesting for the “8-bit (unsigned) IQ gang graffiti” cultural value. They come attached to “cracked” games, although now they've been catalogued separately for those wanting the intros and not the games.

Games, however, were nominally the point of all this. Fortunately for the lawful crowd, the companies that made these old C64 games are largely defunct, so the copyrights don't appear to have any owner (not that everyone considers copyright law to be legitimate). In fact, in the few cases where old programmers have found their games on-line, they have uniformly been delighted to see people playing their old games. Unlike the MAME (multiple arcade machine emulator) project where some industry groups put up a fuss (we assume because they're afraid of emulation spreading to modern console games), there hasn't been a fuss over old C64 wares. Many of us actually paid for the software years ago, so we're probably even legally protected, although there hasn't been much of a problem. One group, the IDSA (Interactive Digital Software Association), tried to shut down some C64 sites, but since they're just a trade group (like the MPAA [Motion Picture Association of America] or RIAA [Recording Industry Association of America], our villains of the moment) they haven't been very effective, as they don't actually represent the now-defunct companies who once held the copyrights. So, be a tad careful just in case, even though I've never heard of anyone getting in trouble over it. (If you're morally opposed to legal strong-arm tactics of threatening web sites with fleets of lawyers, maybe you'll want to collect and spread old C64 games just to be oppositional to the IDSA.) However, if you want to be perfectly pure, you can just stick to the demos and intros, which are very interesting and inspirational.

The Commodore 64 emulators for Linux are known as ALEC and VICE. ALEC is actually my favorite because it runs in console (I live in console), whereas VICE is for the X Window System. Nevertheless, VICE is much more full-featured and will run many programs that ALEC will not. Also, it's released under the GPL. They're both small programs and I recommend getting both of them, particularly because you'll need the ROM images that come with VICE. It's obvious and easy to get started; you can even download binaries if you can't deal with compiling. These projects haven't been maintained in a while, since they're basically complete and don't need much further work, so I don't know of any active web pages. Hence, grab them via FTP from ftp://metalab.unc.edu/pub/Linux/system/emulators/commodore/ (or http to the same address, if you prefer).

As for where to find C64 software, I recommend scouring the Web as you would a used-book store, treasuring rare finds and the web pages of old demo groups. You could go straight to a 10,000-game archive, but that's no fun. Try entering “Commodore 64” or something similar into a search engine—that's fun! If you have to start somewhere, the obvious http://www.c64.org/ and .com are sure to link you to the rest of the Commodore scene. The master collection of C64 scene member interviews known as In Medias Res resides at http://www.imr.c64.org/ and is intriguing for those who want to know what coders/crackers of old were truly like and where they are today. In particular, you can read how the old scene struggled with internal divisions and questions of friendship, community, principle, newbies, lamers, the law, money and the other problems that now confront Linux. If you just want to listen to Commodore 64 music on your Linux box, get Sid Play and check out the High Voltage Sid Collection at http://home.freeuk.net/wazzaw/HVSC/, but don't forget the games!