A look at the business models in use today and how they work.

Open Source is software which has been freed. It allows bits to be copied and reused endlessly. It allows inspection of the source code. It allows new innovations to be built upon old, without having to duplicate past efforts. It is free software with the emphasis on freedom.

This past year has seen an explosive rise in visibility for this curious market. The computer world at large has gained at least a limited understanding and respect for its workings. Much of this attention would have been unimaginable even a year or two ago.

During this time, Open Source has been put under heavy scrutiny. While certain technical benefits are undeniable, every analysis invariably confronts two simple, critical questions: “How does one make a living on free software?” and “Who is motivated to innovate?”

The strength of the answers to these questions will determine if Open Source will achieve its full potential for the greatest possible audience. It must be economically viable.

I will attempt to answer these two questions by surveying the field of current business models and analyzing their financial strength. I will also speculate on future innovations that may alter these dynamics.

Money rests on the axiom that every man is the owner of his mind and his effort ... Money permits you to obtain for your goods and your labor that which they are worth, but not more ... Money is your means of survival.

—Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

The obvious challenge of Open Source is that it may be copied freely, even if purchased initially. So a $10 Linux disc may legally be used to install one machine or a thousand machines. At first glance, it would seem no incentive exists to put effort into improving such a product. Because of this characteristic, Open Source is often equated with a kind of communism: a system that offers something for nothing and exploits the labor of others without rewarding them; in short, a system that is unsustainable because it causes people's self-interest to conflict with the greater good.

These concerns should not be dismissed out of hand, nor taken as factual. The truth is much more complicated. Central to these concerns is the lack of exclusive copyright protections. Copyright and patent laws are not inherently part of the free market; they are intended to create limited monopolies for the companies which own the rights. This is done to reward research and to encourage innovation.

Open Source is a voluntary system that waives exclusive ownership of software in exchange for other benefits. These benefits include wider adoption, faster collective innovation and a level competitive playing field. This makes for a frictionless, dynamic and highly competitive market without the very profitable “vendor lock-in” that is facilitated by traditional copyrighted software.

Despite the resulting competitiveness, several business models have proven to be profitable. These models leverage the unique new possibilities afforded by Open Source, in return for their sacrifice of certain copyrights.

What is still unclear is how these models will generate as much innovation and value as traditional software companies, given the handicap that a person's work can benefit his competition as much as it benefits himself. As we'll see, one of the surprising things about free software is where the innovations have originated.

In the following sections, I'll introduce the markets that are producing innovation and jobs today. These are the research, service and customization economies and the many business models that fall into these groups. Nearly all companies are hybrids of several different business models.

Open-source corporations are important growth engines, but to date, they have built mostly upon the efforts of others. The bedrock of the market is the thousands of individual students and moonlighting professionals who make small and large contributions every day.

These developers are not paid for their efforts. They begin a project with no promises or commitments. They work at their own pace, use their own judgment and set their own priorities. They are the university researchers and basement scientists of software, working together to make their contribution to the world.

Often, these developers are only learning or honing their craft, so many projects fail. Yet out of this soup of individual and group efforts rises some of the best software available today.

Through the Internet, these successful efforts can be instantly copied and put into use world-wide. They can be enhanced and customized by thousands of others. They can continue to evolve like an organism, adapting to new software and hardware architectures as the years go on.

The first and most unshakable answer to “Who will innovate?” is the students and moonlighters, motivated by their desire to learn and create and inspired by the energy and clarity of tackling new problems. The profit-oriented market may fail, but these software research activities will go on. Slowly, surely, they will continue to add to the body of free software available to the world.

Yet despite the best efforts of the students and moonlighters, their software has common flaws. Development goals are driven by the author's own needs, resulting in software “by developers, for developers”. The threshold at which a developer is satisfied with ease of use is much lower than for typical users. These are truly research projects, with all the beauties and warts that implies.

In the cases where beauty has outweighed warts, a critical mass of technical and non-technical users has been built. Apache, Linux, Perl and many other programs have made this breakthrough to mass market utility. This expanded base of consumers has driven the need for many support services built around the software. These services add polish and value to the base provided by the initial project.

No one is required to pay for any services. Given only a Net connection, they can download what they need and figure everything out themselves. However, many consumers find their time more valuable and therefore seek services to make their lives easier. This is where “commercial” Open Source steps in to distribute the software, provide technical support and educate users.

Distribution

The Internet is great for downloading small software, but for larger products it is too slow. Also, finding the software you want among the jungle of projects on the Web can be difficult.

From this need rose companies like Red Hat, Caldera, SuSE, and Walnut Creek. On one convenient CD-ROM, you have an organized collection of the best available software applications. These companies are achieving significant revenue and earnings with these services.

Opportunities exist for further specialization. LinuxPPC has made a solid business out of focusing on the PowerPC market. A small company could take this further by taking one of the most popular (Dell, Linux, eMachines) PCs and producing a distribution that is tailored and tuned to that hardware. It could guarantee that all devices are recognized and install flawlessly. It could optimize every program to the particular processor used on that machine. You could imagine Intel co-marketing and co-developing with a software company to optimize for their latest chips.

Open Source can be a key in the drive towards mass specialization of computer products and services. As the overall size of the market increases, more opportunities will be created in these small niches and sub-niches. All of this is made possible by the full access to source code that free software provides.

Technical Support

When a single company owns exclusive rights to a software product, it is obvious where the most informed technical support comes from: if you buy a Microsoft product, you go to Microsoft for technical support.

The fact that Open Source does not have an exclusive support provider has repeatedly been portrayed as a weakness. This is a fundamentally flawed notion. Rather, Open Source allows a whole market of support providers to compete on a level playing field of equal access to the code.

Through this heightened competition, the level and quality of support is capable of rising above the best standards of today's closed software market.

Red Hat, LinuxCare and many other companies and individual consultants have stepped up to serve this market. Early in 1999, IBM recognized these extraordinary opportunities and announced Linux support and consulting services. The competition between these companies will become intense, and customers will be well-served.

If open-source support services can achieve their full potential, it will become a major selling point for corporate users and consumers. Innovations in providing these services will provide the foundation for many viable new businesses.

Education

O'Reilly & Associates has built a booming book publishing business which topped $40 million in 1998. More than half of this revenue was from books about free software topics.

As the market grows in size, more educational services will be needed. These are significant opportunities, since any educator, author or consultant can delve into the inner workings of the code to produce definitive training materials for a subject. By working on and teaching about specific areas, a valuable reputation can be created. (See Table 2, Linux Consultant Survey.) Several of the most successful consultants built their businesses by being a recognized world-wide expert in a particular technology.

The next step beyond servicing existing software is the creation of new applications to solve outstanding problems. This may be in the form of hardware devices that come preconfigured for a particular need. Or it may be through employees or consultants who configure and enhance software for particular needs.

In a world dominated by a single vendor, there are limits to the innovations a new product can provide because of high prices, too few features, too many features, logo requirements, etc. Many interesting new applications are suddenly possible when these shackles are removed. You just need freedom to customize.

Hardware Bundles

Hardware preloads and bundles are some of the most compelling uses of free software, because the cost of developing or enhancing free software for the machine can be included in the price of the hardware.

One example is the Cobalt Qube (http://www.cobaltnet.com/). This is a space-age blue 18.4x18.4x19.7cm server appliance running Linux on a RISC processor. It is a general purpose workgroup server for e-mail, Web, etc. Having full access to the Linux source code gave Cobalt the capability to fully customize the software for this uniquely simple but very powerful hardware platform. (See “Cobalt Qube Microserver” by Ralph Sims, October 1998.)

Another is the Snap! network storage server from Meridian Data (http://www.meridian-data.com/). It's a fixed-function server appliance that shares disk space on the network. It is built from custom hardware combined with open-source software. Consumers don't need to know it uses free software; they just need to know what it does. Customers expect the price of network storage to scale with the price of disk storage, so the hardware and software costs of using a proprietary software system could have greatly reduced the attractiveness of the product.

Obviously, one big advantage is having no per-device software royalty. This is particularly true for price-sensitive, high-volume products. In a few years, we may find dozens of companies embedding open-source operating systems and applications on millions of small, fixed-function hardware devices.

IT Professionals

Beyond hardware devices, there is a need to customize and adapt software applications to the exact business processes and needs of an organization.

This always requires some custom work. Most medium and large organizations have a crew of IT professionals whose job is to customize hardware and software to make the business run more smoothly. These professionals like to start with the most functional products possible and customize from there. This has meant proprietary software in most cases.

Recently, open-source software has achieved levels of functionality that match proprietary software in many cases and has the advantage of not being tied to one vendor for support or product updates.

Rather quickly, it may become cost-effective to customize free software, rather than pay for thousands of licenses of commercial software on which to build. This shift in the market will require a growing number of professionals who specialize in open-source software.

This is perhaps best reflected in the salaries of IT Professionals. A 1998 salary survey of 7189 professionals asked which operating system they primarily used. Of those who reported Linux as their primary OS, their salary was $61,027 US vs. an overall average of $60,991. Linux salaries had increased 16.5% from the previous year, representing the fastest salary increase of any system (source: Sans Institute).

In-house staff is not the only option. Again, because of the freedom to inspect and study the software down to the lowest levels, a competitive industry is able to grow to serve whatever needs arise. The resulting alternative to in-house staff is a competitive market of independent consultants.

Consultants

When the cost of the software goes to zero, the value is in customizing for specific problems. Consultants already make their living providing these per-hour or per-project services. Open Source is not a sacrifice; it is an opportunity.

One example is comprehensive support. Most business want a single point of contact to take full responsibility for getting a project done. With closed source, contractors are at the mercy of bugs and limitations in the operating systems and applications they purchase. In effect, they cannot guarantee success. They do not have full control of the technology.

With Open Source, they have complete access to solve every problem, no matter what level or layer it occurs in. A small company with a skilled force of engineers can provide a level of comprehensive application-to-operating system service that only IBM or HP or Sun can provide today, and probably at much lower prices.

To get an understanding of the size and health of the Open Source consulting market, those registered in the Linux Consultants HOWTO were surveyed. They were asked the following questions:

How many consultants at your company are involved with Open Source work?

Approximately how much money did your company (or yourself, if independent) earn in 1998 on Open Source-related work? (Convert to US dollars)

In 1999, based on numbers from recent months, how much do you expect this to increase/decrease? (as a percentage)

In 1999, do you believe it is possible to make a living doing Open Source consulting work? (yes/no)

This is a very diverse group of VARs, integrators and consultants. Over 50% are from outside the U.S., where the cost of living may sometimes be lower. In most cases, open-source work is just a piece of the total business. While this is certainly not a scientifically rigorous study, it does give some flavor of the market.

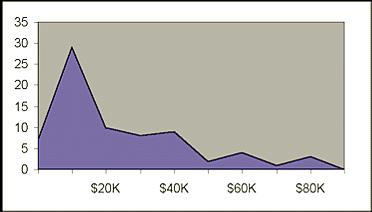

A key point from the survey is the importance of being a “jack of all trades.” You must focus on serving the needs of the customer, including doing work on closed source. In 1998, the median earnings per consultant on Open Source alone were not enough to make a living, and only 12.7% of the consultants made more than the $61,027 salary of IT professionals mentioned above. Business has picked up dramatically in recent months, however. As a whole, the consultants were very bullish on the coming year.

Figure 1. Survey: Distribution of Earnings

In the previous sections, we've covered the current business models that provide a living for employees, and innovations for consumers. There are certainly strengths, but the market is still tiny compared to traditional shrink-wrapped software. Young companies with new ideas are needed in order to grow the market.

Capital is the fuel for companies that will serve any new market. This money may come from the on-going operations of the business or from banks or investors. What is the current environment for getting this funding?

Venture capitalists, the investment partnerships that fund high-risk/high-return companies, are skeptical so far. Their analysis of these opportunities keeps coming back to a critical point: Open Source, by definition, eliminates the barriers of entry to a market. How can a company build a sustainable market advantage if their work can immediately be used by a competitor?

Given this limit on the upside, only a limited number of open-source companies have received funding. These companies have identified key factors to protect them from competitors. For Red Hat, it is a strong brand. For Sendmail, it is having an open/closed mix in their software product line. For a company like Cobalt Networks, it is combining closed hardware with open software. As this market matures, more companies may achieve profitability and attract investment dollars for everyone.

Until then, companies must bootstrap themselves. Ironically, this is feasible because of those same low barriers to entry that scare off investors. An open-source company can build on the past efforts of others, meaning less capital is required to start the company.

In summary, what are the problems that companies must solve in order to grow the market in new directions?

The financial motivation for innovation must be stronger. Most of the current successful business models other than consultants make money off “secondary” services, rather than the software development itself.

Open Source is still largely “by developers, for developers”. To achieve mass market success, it must become more customer-driven and consumer-friendly.

Traditional software products harness the free market to solve these issues. Consumers pay to buy a software product if it meets their needs, which means it must be very polished. Successful products are profitable for the companies that create them. Unsuccessful products die off. Through these mechanisms, good developers make a living and consumers get good choices.

Open Source needs to create systems to provide these consumer checks and balances.

The business models described throughout this article are by no means a comprehensive list. This is a young market we are only beginning to understand. It could yet defy the skeptics and evolve into something that serves customers better and is financially strong.

Part two of this series will explore one particular possibility in this universe of interesting but unproven ideas—a consumer co-op for software contracts. It uses the Web to let consumers commit funds up front to pay for the development of specific applications, feature enhancements or bug fixes critical to them. Resources are pooled, so each person pays only a small portion of the total cost. It is a system compatible with, and tailored to, Open Source. I will analyze this idea in detail, describe an attempt to create a web service which provides the necessary mechanisms and speculate how this system might affect the progress of the open-source market.

With this idea and many others, the open-source market is a fascinating mix of possibilities and dangers. In recent years, it has grown from thousands to millions of users. Several profitable companies are now serving the needs of these consumers.

The next few years will certainly see continued innovation from the open-source research community. From the business side, it remains to be seen whether the current momentum will continue or be struck down by market realities. It may very well depend on the innovations created by the upcoming generation of open-source entrepreneurs. It's a free market. May the best products win.