A mission-critical application for 580 Linux computers.

The Totalisator Administration Board of Queensland (universally and affectionately known as the TAB, phew!) administers to the considerable betting needs of the Australian public in this sunny state of relaxation and fun. Virtually every pub (confusingly called a “hotel” here), club and high street has a high technology betting center for the Aussie punter (bettor). All to the tune of $1.3 billion Australian a year (about $900 million US)—making Queensland one of the biggest betting communities in the world, per capita.

From Bundaberg to Coolangatta, from Cairns to Woolongabba, the surfers and holiday makers on the Gold Coast and the farmers in the far outback are delighted to be ignorant of the fact that all of this technology is delivered and controlled by a massive distributed network of over 580 Linux computers running the TAB's own betting software. These Linux “branch controllers” are in every betting shop, agency, hotel and club to:

Control the video displays of information to help the punters decide which horse to back.

Place bets.

Communicate to and from the head office mainframe computers in Brisbane.

Let the punters access their bank funds through EFTPOS banking terminals (Electronic Funds Transfer at Point Of Sale).

In this interview, Stephen Wockner, Manager of Customer Systems and an 11-year veteran of TAB, takes us through the history of the TAB's use of Linux and some of the business imperatives that led to its adoption over more conventional systems at a time when such a decision was a very brave one.

Stephen (wockner@tabq.com.au) has been involved in computer systems development including VMS, Unix, NT and PC systems for over 17 years. He holds a master's degree in Technology Management. He enjoys both technical and business challenges, and Linux has certainly been able to provide them.

Bob: Please introduce the TAB for us.

Stephen: In the beginning, the Totalisator machine was invented in Australia in 1907—a mechanical device for calculating odds against bets placed and prize money. It's now in the PowerHouse Museum in Sydney. The TAB itself started business in about 1962 and is a statutory authority set up by the government with a board of directors appointed by the government—it will be an independent corporation next year. The product, mainly small bets on daily horse racing, is an inexpensive form of entertainment in pubs and clubs across the country and overseas where punters match their wits and knowledge of the horses against each other.

Out of every $100, the TAB returns $85 in prize money to the public with $6 going to taxes, $6 to the racing industry to fund the races and $3 to run the TAB; so, when you appreciate the scale of the organization across such a huge territory, it's a pretty lean and mean operation.

Bob: When did the TAB first implement Linux, and why?

Back in 1990, we had a system based on QNX2, a proprietary UNIX-like system with real-time extensions. This ran in every branch on [Intel] 386 machines with 4MB RAM, and controlled the entire shop, including running communications back to the head office over 2400 baud leased lines. It supported several video display devices to show punters the action and input devices for taking bets. These were pretty specialized “mark sense” card readers and printers.

It was a blow in 1994 when the manufacturers of QNX2 announced that it would be discontinued in favour of a new, better system called QNX4. The new system was to be POSIX compliant and full of new features to make it a true general purpose operating system, which unfortunately we did not need. QNX4 also came with a much bigger footprint—it would essentially require us to upgrade all of our betting outlets (then 250) to much larger hardware.

That led us to start looking around for alternatives—after all, if we have to upgrade the hardware, then we want to minimize the impact on the organization and the total cost as well as take advantage of newer software technology.

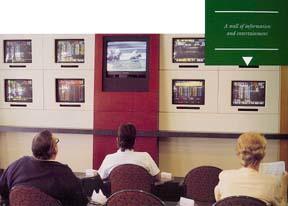

Figure 2. Mini-TAB in Use

Figure 3. Installed Mini-TAB

Figure 4. Mini-TAB

Bob: What other systems did you investigate?

Stephen: We considered most of the operating systems available at the time, including DOS plus an add-on real-time multitasking manager, Windows 3.1, an early NT, a beta version of Windows 95 (Chicago), OS/2, Coherent UNIX, Xenix, Solaris, QNX4 and Linux 1.0.

Bob: What led you to choose Linux in the end?

Stephen: The process was a very objective one. We had no religious or other adherence to UNIX per se—we just had very specific business problems to address. In the end, these came down to a bottom line of cost minimization and the ability to do the job in over 500 locations, some very remote.

A number of the factors that went into the decision were:

Functionality: it had to run on appropriate hardware of the day—486 with 16MB RAM in 1994, upgrading to Pentium today—and had to support the range of exotic devices we need. This included four TV displays via a black box controller, a four-port async port for displaying results and an RS485 multidrop LAN to control wagering terminals, typically four.

Performance: support for particularly heavy interrupt-driven, heavily loaded, synchronous communications back to the head office using the X.22 protocol over 2400bps HDLC (high-level data link control).

Reliability: a system crash could easily lead to ugly scenes—punters can be pretty impatient when the race is only two minutes away. No, they are not happy to be told the system is rebooting. What you have to remember is that many punters watch the odds and place their bets at the last minute. Reliability and performance under pressure are key requirements for our computer system.

Maintainability: many of our installations are not in town. They can be in the far north or outback areas with barkeeps who are not computer savvy or even permanent staff. The systems must be able to look after themselves with some remote management from here in Brisbane.

Continuity: we had to be assured that the system would last a long time. Our systems have a life of five to seven years, and we learned the hard way that proprietary vendor support could not guarantee this. Also, we want to be sure that code written today will run on tomorrow's processors. So, as far as hardware is concerned, we use commodity level Intel PCs—the the fewer proprietary “improvements”, the better.

Development environment: our philosophy is “insourcing”. Our applications are specialized and developed in-house or with third-party suppliers—all with source code available to us. A good development environment was important.

Purchase and maintenance costs: licensing costs of the operating system add up quickly when 580 systems are involved. Some vendors cope better with this than others.

Bob: How did the different systems shape up?

Stephen: First of all, it quickly became obvious that Windows NT just could not cope with the the heavy communications loads and interrupt rates we would throw at it—even with top-end PCs. Windows 95 was pretty much the same. Running on a 486 with 16MB RAM could not even match the old QNX2 systems on a 386 with 4MB RAM. Reliability was another concern—the system had to keep running—the infamous “Blue Wall of Death” could become literal if punters are frustrated in placing their bets!

DOS with an add-on multitasker was just too difficult. We predicted continuity problems if we chose a third party supplier, and technical difficulty and delay if we wrote our own.

Coherent and Xenix were just too old—we had no confidence that support would continue. Similarly, OS/2 was technically nice but had a very limited future.

Solaris and other UNIX systems suffered from the same problem as QNX4—a big footprint, as well as unreasonable licensing rates. We were also uncertain about continued vendor support over our time scale of five to seven years.

In the end, Linux was the only system that could measure up on all fronts. The purchase cost was nice too, but by no means the most important factor—we would have been perfectly happy to pay a license fee (as we had with QNX2) for the right system. At that time in 1994, Linux was growing rapidly, and we could see that it had a great future.

Bob: How did the implementation go?

Stephen: We started work in early 1995 and made the first release of production systems in 1997. Some work was needed in getting the X.22 HDLC and RS485 networking going and porting the main betting application from the QNX2 system. Apart from having to fix some minor bugs, it went very smoothly.

As well as running our code and supporting our devices, Linux just keeps on going. So far, we have not had a riot at a betting shop because of a computer failure—in fact, our biggest reliability problem is power surges from the massive tropical storms we get here. Lightning can rip through even an e2fs disk and trash it. We don't know of many systems asked to operate in such a hostile and effectively unattended situation.

To cope with weather and other emergencies, we built a rescue partition into each system which can be booted remotely and which does just one thing—it rebuilds the master partition and restarts the machine. In this way, we have a timely repair for the most frequent service call—all without sending a technician 700 kilometers into the bush. We even have a facility (as yet unused) to reinstall the previous version of software in the event that we make a bad release.

Bob: Which version of Linux did you start with?

Stephen: Well, we're now on Slackware 3, kernel 2.0.14 but initially we used 1.0 and then 1.1—yes, don't look horrified, we actually ran production systems on the developer's versions and they were rock-solid—we needed the new features. Essentially the access to source code allowed us to customise line drivers for our own purposes and to support ourselves. With the source in our hands, we could be confident we'd survive. In fact, we found ourselves fixing bugs in the 3c509 drivers.

Bob: And contributing them back, of course, as good netizens?

Stephen: Well, not always—the crazy thing was that, like many corporations at the time, the TAB distrusted the Internet. We are, after all, a major financial institution with high security requirements. We simply had no Internet access available at work—we used InfoMagic CD-ROM releases and had programmers hacking at home to download and upload additional code. Supporting Linux without the Internet was a major pain, so we may well have been consumers more than contributors in the early days. Today, of course, we have a full Internet connection—you can see us (and place bets on-line) at http://www.tabq.com.au/.

As far as contributing finished systems back to the community, we work with our partners—our contracts generally allow them to produce products and subsystems based on their work for us, so this code finds its way back into the system through them. Obviously, our top-level betting applications are too specialized to interest many people, and the issue of security is always present. We are mainly talking about subsystems.

A good example of this synthesis was the 20-port X.22 multiplexor card developed for us by Mosaic Pty Ltd and now marketed by them. It provides a very economical PC-based communications front end to our Unisys mainframes.

Bob: What about the end users? What advantages do they get from Linux?

Stephen: The advantage for them is they don't know it's there! It's reliable—it doesn't just fall over. It's simple for temporary staff or computer novices to learn and use—no mouse is involved, just a very simple set of cascading menus that are quick to learn and hard to cause trouble.

Bob: And the business of I.T.—how does that benefit?

Stephen: Linux truly helps us implement insourcing, which in turn allows us to maintain a tight loop for developing new features in our systems. The marketing people and top management think up new ways to bet, and we can support their ideas quickly. We're fairly fast on our feet, and time to market is a key issue.

All of this is done at a fraction of the cost of using a large vendor and becoming dependent on their proprietary lock-in features and escalating support costs. Most vendors are sales driven, after all. For example, if we buy a widget in year 0, how many of them are being sold in year 5 or 10? What motivation for continued support is there? We are confident that Linux will keep on pumping out the features we need, yet allow us to migrate our installed base at a rate we can control, not because some vendor needs income from a new version. So, the Open Source approach gives us control over continuity as well as the ability to exclude code bloat.

Efficient maintenance of such a huge system is also a key to keeping costs down. Sending a technician to many of the branches is a two-day affair with plane tickets and accommodation involved. Linux allows us to remotely monitor and maintain the systems—even install the next great version—all over a 2400 baud/s line!

Figure 5. The Linux Team at the TABQ

Figure 6. Linux Network Controller Glass House

Bob: Any problems or worries using Linux?

Stephen: Adopting it in 1995 was a big step for a corporation and was accompanied by the usual fears and objections of “where's the vendor to support us”. In fact, that fear has turned out to be a furphy (rumour)—the support we get off the Net is better than most large vendor's support, and our “insourcing” philosophy lets us modify the source if we get into a tight spot.

We have had to tool up to be independent and this is the downside. We needed to quickly develop a high level of skills and core competencies in-house and then make sure we keep the staff. We do this in the time-honoured fashion—we pay our engineers in the upper percentile and maintain a dual career path for them as they mature into either management or specialist engineers. Many companies don't provide this growth path and then wonder why their best people shuffle off.

Some of the wars over KDE vs GNOME and Linux Standards caused us to pause for thought—but by and large, it's a healthy battle and we would worry more if there was apathy over these issues. We are reassured that Linux is developed by a tight coherent community passionately concerned about the product.

Bob: What is the status quo?

Stephen: Currently, we have about 580 branch controllers installed with Linux systems, and we will continue to cycle out old 486 QNX systems in another 50 sites. We buy top-of-the-line commodity PCs—Pentium IIs now—and harden them on the developer's desks. As each batch of 50 or so comes in, the last lot goes out to the branches. We then work them to death—I mentioned the seven-year life cycle. The problem with that is we can't even donate our old stuff to worthy causes, as our old machines are really, really old and tired by the time we're through with them.

The ability to run Linux is obviously a prime acceptance criteria for all new equipment.

Bob: Any other applications for Linux?

Stephen: In another project, we have been putting Linux-based “mini- TABs” into the smaller outlets like pubs and clubs which don't justify the full system. These are about the size of a Coke machine, and we can make them at a reasonable cost—our counterparts in other states are not able to do this because of the high cost of mainframe support. Linux allows us to use a true client-server approach while preserving reliability to mainframe levels. We can also provide more information to the end user via Linux client-server, e.g., each screen supports 30x80 characters whereas the mainframe versions run at 24x30 (Teletext).

At the head office, we also use Linux as an authentication server for the entire network—no bet gets placed until the remote system is authenticated by Linux.

We also have about 20 boxes running QNX4 as a communications front end to the mainframe and talking to all the Linux boxes in the field. This is in place of proprietary front ends costing $600,000 per 20 lines. Unfortunately, Linux doesn't have quite enough real-time oomph to do this yet, but as hardware speed increases and real-time features get added to Linux, we'll keep an eye on it.

By the way, the whole head office of mainframes and front-end processors and authentication servers is mirrored at a separate site in Queensland in case of catastrophe.

Finally, we have about 50 Linux machines in our development area which all run the X Window System and various desktops—we like Enlightenment, for example. The newer development environments are a very nice plus for us and really endorse our decision to use Linux—for example “Nedit”, which looks much like Virtual Studio and provides excellent productivity. Things like gdb are obviously well-used, but the nice new GUI front ends help keep us productive.

Bob: What about the Internet?

Stephen: We see the Internet as the preferred medium for the future of remote betting—in other words, phone betting. Obviously, it provides information in the most timely manner possible to our punters, which is the name of the game. By contrast, newspapers provide form and odds information which is over a day old, and radio and TV provide information only when they feel like it. Our customers presently use both phone or Internet, depending on which is more convenient for them. So that's a tip for punters—use the Internet for the most up-to-date information on racing.

We use Linux as Internet and security servers to provide digital certificates for our registered punters on the Internet. A Java applet on our betting page keeps information on their screen up to date—data is 30 seconds old or newer. You can't do better than that anywhere except by going into a TAB agency. The digital certificates issued by the Linux box have a special security feature—one we feel is essential in a financial environment—if a customer believes their certificate is compromised (e.g., stolen), they can call and cancel it within minutes. Not many (if any) certification authorities can provide this option.

Bob: And in the future?

Stephen: We have our telephone betting centres—call centres, really—with about 550 operators in Brisbane and 110 on the Gold Coast about an hour's drive south, all running on NT. We are at the testing stage of a new Linux version, which will use a digital sound system to store all calls to huge disc farms. This will replace the monstrous and antiquated tape recording system we have now and provide faster retrieval—we keep the recordings for 28 days in case of a dispute with a punter (“I didn't say put $10 on `Neddy', I said `Freddy'”). This will be deployed late next year, and by the end of 1999, we will be running well over 1000 Linux machines.

The back-end mainframe is being converted to run on an NT platform. Subsequently, many of the applications written for NT are then ported to a Linux environment. In this conversion from NT to Linux, we'll be able to take advantage of the C++ code portability that we have always striven to maintain—we have a common set of libraries and take great advantage of reusable C++ code. For example, every system, whether NT, Linux or QNX, uses a common memory-based model of the entire betting system—almost an in-memory database. It's the same on all machines and is constantly kept updated.

On another front entirely, we are thinking of moving to satellite dial-up communications instead of leased line because Linux should be able to do this well. This could save us a big chunk of the $2 million we spend a year on fixed 2400bps lines and would let us use 19.2Kbps into the bargain.

Figure 7. Breakfast Creek Hotel in Queensland

Bob: Any advice to others in the corporate and government I.T. world?

Stephen: Firstly, we have found through experience that it is much better to avoid the big bang approach to new system development as much as possible—where we have applied incremental improvements to individual components, we've had much greater success.

Linux suited our particular and special set of business problems in an objective evaluation and has produced the best and most cost-efficient, functional and reliable long-term solution. We were not fazed by the lack of a vendor standing behind the system even though it is, in every sense of the word, a mission-critical application. We feel that the FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt) about vendor support is often a poorly disguised excuse for proprietary lockin. Of course, we have an insourcing and self-dependent philosophy which may not suit all entities.

Our cost savings using Linux goes far beyond the area of zero licensing fees into the less easily quantified areas of good old-fashioned reliability, serviceability, upgradability and continuity.

Bob: Thanks very much!