What I looked for in this book, among other things, was information that can actually be used.

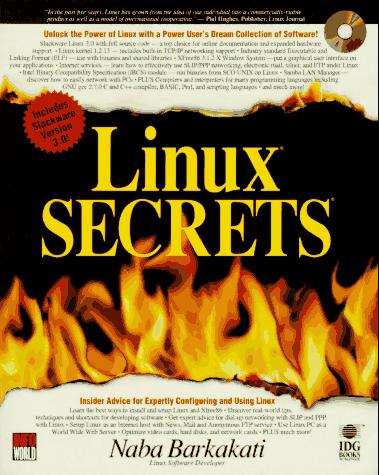

Author: Naba Barkakati

Publisher: IDG Books, 1996

ISBN: 1-56884-798-X

Price: $49.99 (includes CD)

Reviewer: David Alan Black

“Naba Barkakati,” says I when I received the review copy of Linux SECRETS, “That's the guy who wrote The Microsoft Macro Assembler Bible.” I'm a low-level guy from way back, and in my DOS assembler programming days, Naba's books always stood out for their readability, seriousness, and thoroughness. Linux SECRETS continues this tradition.

I'd be bluffing to generalize too much about “what to look for in a mass-market Linux book”, because this is the first one I've owned. So I'll be specific. What I looked for in this book, among other things, was information that can actually be used. In other words, I kept it close at hand in order to see whether or not I ever actually referred to it. The answer is that I did—not every day, but enough to continue to keep it close.

I also tested the book's clarity and utility by using its instructions for a project I'd never done before—namely, writing a man page. The instructions for this neither are, nor pretend to be, a groff tutorial; but they make sense and they work. (You can judge for yourselves—see Figure 1.) It's always been my impression that Naba has a gift for explaining, and this book confirms that impression.

Linux SECRETS covers an enormous amount of material. The table of contents alone is a full twenty pages long, with chapter titles such as Installing Linux; Secrets of X under Linux; Secrets of Linux Commands; Scripting with Tcl/Tk; Running a Business with Linux; Networks; Modems; Printers, and Text Processing. The book's stated goal is to serve as “a practical guide that not only gets you going with the installation and setup of Linux, but also shows you how to use Linux for a specific task, such as an Internet host or a software development platform.”

The book views different topics at levels of magnification; it explores some topics in telescope-like detail; for others, it uses binoculars; and sometimes it looks through those devices from the other end.

The topics presented in the most detail include installation and other setup-related procedures. My experience on both sides of the virtual help desk suggests that no single written source will ever get everyone from blissful ignorance to Linux Nirvana with no problems and no outside help; but anyone who studiously follows Naba's installation chapter will see that it comes very close. Along the way there is much supplemental information, such as remarks on the 16/32-bit OS distinction, sidebars about the BIOS and DOS, and so forth.

While we're on the subject of installation: the book and CD-ROM are Slackware-oriented. If you have reason to care—for instance, if you're starting out and have decided in advance to use a different distribution—you should be aware that the only distribution on the CD-ROM is Slackware 3.0, and much of the treatment of installation, setup, and upgrading assumes a Slackware-based system. You should also keep in mind that a great deal of the material in the book is distribution-independent.

Also covered in considerable detail is the topic of hardware. There's actually a chapter called “Computers”, which forms a bridge between a general look at hardware architecture and Linux-specific compatibility concerns. Input devices, CD-ROMs and sound cards, video hardware, disk drives, printers, and modems all receive their own chapters. As always, these chapters include information about how things work generally, as well as detailed discussion of how they work under Linux.

Shifting from telescope to binoculars, we find coverage of the things you can actually do with Linux, centering around Part IV, “Using Linux for Fun and Profit”. Almost half of this chapter is devoted to networking (setting up a server, running an ISP, and so on); and while the binoculars perhaps get picked up backwards here and there, overall this section contributes much—not only in practical advice, but in making the point that Linux has real sweep as a platform for many projects.

At the sketchier end, the book includes sections on such topics as vi, shell programming, emacs, Perl, and Tcl/Tk scripting, as well as a “Linux Applications Roundup” which introduces several other editors and applications (gzip, Workbone, Ghostscript, etc.). Much of this material, of course, is second nature to many of us, but I have found some of these short sections very handy for getting an overview of a topic and deciding whether I want to pursue it. In this respect, the less detailed sections can be very helpful.

Overall, the lesson learned from breaking contents down by level of magnification is that while no one is likely to need or use everything in the book, many people at varying levels of expertise with Linux will find a good fit between their needs and the book's coverage. I'll just add that the author provides guidance on where to go for further information, both interspersed throughout the text and listed in a “Linux Resources” appendix. (Of the various resource subheadings, “Magazine” is the only one that appears in the singular!) Even if some of the pointers to resources remind us how quickly things change (e.g., the inclusion of comp.os.linux.help), it helps keep you in touch with the world of Linux.

Linux will always be (I hope) too dynamic a thing to be captured fully on paper. But while we watch it take off, explode, spread, and do various other non-static things, it's nice to have written works that are lucid, informative, and in touch with the spirit of the project.